Tarrare, the Greatest Glutton of All Time

By Bess Lovejoy

Today's competitive eaters are renowned for consuming dozens of hot dogs in a single sitting, but the unusual eaters of old performed much weirder feats. Medieval reports describe people consuming hearty helpings of stones, spiders, and snakes, among other poisonous things, and showmen were making a living touring Europe on the strength of their strange stomachs by the early 17th century.

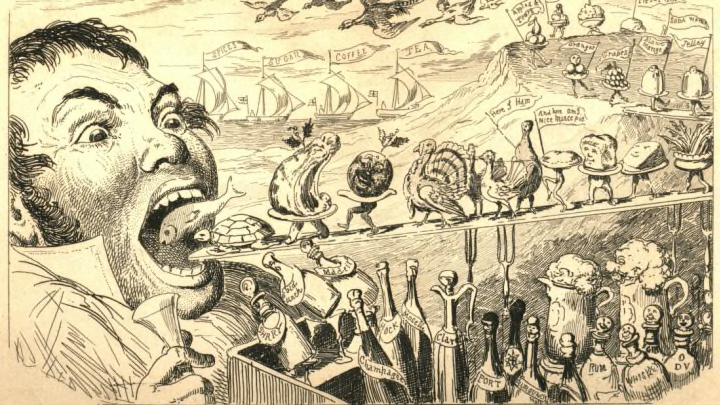

“The Great Eater of Kent,” a 17th century English laborer named Nicholas Wood, entertained fair-goers at country festivals by consuming 60 eggs, mutton, three large pies, and a black pudding in a single sitting. In the 18th century, one Charles Tyle of Dorset ate 133 eggs in an hour alongside large quantities of bread and bacon (he then complained he hadn’t had a full supper). In 1792, according to medical historian Jan Bondeson, a French showman named M. Dufour ate a particularly Luciferian banquet in front of a packed house in Paris, including an hors d’oeuvres course of asps in hot oil, dishes of tortoise, bat, rat, and mole, an entrée of roast owl in a sauce of “glowing brimstone,” and a dessert of toads adorned with flies, crickets, spiders, and caterpillars. Dufour then swallowed all the candles on the table alongside a flaming glass of brandy, and opened his mouth wide so the audience could glimpse the flickering flames inside his throat.

But the most amazing eater ever recorded is Tarrare, an 18th-century French showman able to consume his own weight in beef by the time he was 17. It’s unclear whether Tarrare was his real name or a nickname; “bom-bom tarrare!” was a popular French expression at the time used to describe powerful explosions, and Bondeson speculates that it may have been applied to Tarrare because of his prodigious flatulence.

Tarrare’s appearance was reportedly relatively normal, except for an enormous mouth stretched wide over badly stained teeth, and a distended belly that hung so low he could wrap it around his waist when it was empty. He was also said to sweat constantly, and emit a powerful odor. According to a report in The London Medical and Physical Journal, “he often stank to such a degree, that he could not be endured within the distance of 20 paces.”

Born in the French countryside near Lyons in the early 1770s, Tarrare ate so much that his parents kicked him out of the house when he was in his teens. According to Bondeson, Tarrare then spent a while touring the French provinces “in the company of robbers, whores, and vagabonds” before taking up employment with a traveling quack, swallowing stones and live animals to draw attention to the charlatan’s dubious medical cures. In 1788 he left the quack’s employment and made his way to Paris, where he performed on the streets, swallowing basketfuls of apples, corks, flints, and other objects. After one such show, he suffered an acute intestinal obstruction and had to be carried to the Hôtel Dieu hospital. After being treated by the surgeon there, he offered to show off his talents by swallowing the man’s watch and chain. The surgeon was not amused, and replied that he would cut Tarrare open with his sword to recover his valuable possessions.

When the revolutionary wars broke out, Tarrare signed up with the French army. The military rations weren’t enough for his appetite, though, and he was soon taken to the hospital at Soultz complaining of exhaustion. Despite being given quadruple rations, and chowing down on all the poultices in the apothecary, his needs remained unsatisfied. The military surgeons were so amazed they asked to keep him in the hospital for experiments. While there, Tarrare ate a meal intended for 15 German laborers, including two enormous meat pies and four gallons of milk. He also ate a live cat—breaking open its abdomen with his jaws, drinking its blood, and later vomiting up the fur and skin—as well as puppies, lizards, and snakes, which were said to be a special favorite. The doctors, which included one M. Courville and Pierre-François Percy, one of the greatest military surgeons of his day, declared themselves astonished.

After a few months in the hospital, the military board inquired about when Tarrare might return to duty, but the doctors were unwilling to part with their fascinating subject. As Bondeson describes it, M. Courville came up with an ingenious, if bizarre, plan to make Tarrare useful for both science and the military—he would courier documents with his own body. First, Courville asked Tarrare to swallow a wooden box with a document inside. Two days later, Tarrare returned from the hospital latrines with both box and document in good condition. After a repetition of the experiment at French army headquarters on the Rhine (Napoleon may or may not have been present), Tarrare was officially employed as a spy. His first task: deliver a message to a French colonel held prisoner in a Prussian fortress.

However, Tarrare’s mental abilities were apparently dwarfed by the powers of his stomach. According to a report in The London Medical and Physical Journal, Tarrare was “almost devoid of force and of ideas.” And so while the army officers told Tarrare he was swallowing papers of key strategic importance, the note he was entrusted with simply asked imprisoned French colonel to report back on any information he might have about Prussian troop movements.

It turned out the French officers were right to be concerned: Tarrare was captured outside the city of Landau almost as soon as the mission began. (This may have had something to do with the fact that he didn’t speak a word of German.) The poor glutton withstood a strip-searching and whipping without betraying his cargo, but after a day with the Prussian counter-intelligence, he finally confessed. The Prussians tied him to a bog-house and waited for his digestive system to deliver the goods. When it complied, however, they were enraged to discover such a banal message inside the wooden box—they believed, as did Tarrare, that he was carrying crucial military intel. The Prussians beat him brutally, then subjected him to a mock execution, letting him get as far as the scaffold before calling off the executioner.

Understandably terrified by his ordeal, Tarrare returned to the hospital begging Dr. Percy to cure him. Unfortunately, all of the reported solutions for excessive eating that Percy tried—tincture of opium, sour wine, tobacco pills, copious amounts of soft-boiled eggs—proved to be in vain. Tarrare found himself unable to live on the hospital’s food, and snuck out to butcher shops and back alleys, fighting street urchins and animals for scraps of decaying carrion. He even drank the blood from other patients at the hospital, and was kicked out of the hospital morgue several times for trying to eat the corpses.

Several of the doctors complained that Tarrare would be better off in a lunatic asylum, but Percy defended his presence at the hospital. That is, until a toddler mysteriously disappeared from the wards. Tarrare was the prime suspect, and the furious doctors and porters finally drove him away from the hospital for good.

For the next four years Tarrare’s whereabouts are unclear, but in 1798 he showed up at a hospital in Versailles, so ill he could barely rise from his hospital bed. Tarrare believed his troubles stemmed from swallowing a golden fork, but the doctors recognized him as suffering from advanced tuberculosis. About a month after Percy was notified of his admittance, Tarrare was struck with terrible diarrhea. He died a few days later.

The doctors were loathe to undertake an autopsy—apparently the corpse became “prey to a horrible corruption” soon after death—but the chief surgeon at the Versailles hospital overcame his disgust and opened up the cadaver. He found that Tarrare’s gullet was unusually wide, and when the jaws were forced open, that he could see all the way down into Tarrare’s enormous stomach, which was covered in pus and filled almost the entire abdominal cavity. The liver and gallbladder were similarly oversized. According to The London Medical and Physical Journal, "The stench of the body was so insupportable that M. Tessier, chief surgeon of the hospital, could not carry his investigation to any further extent."

The cause of Tarrare’s extreme gluttony has never been diagnosed. According to Bondeson, no case resembling Tarrare has been published in modern medicine. And while the reports of his eating habits beggar belief, they were recorded by some of the foremost medical authorities of his time, and well-known among the Parisians who delighted in his macabre displays. Percy wrote in a memoir: "Let a person imagine all that domestic and wild animals, the most filthy and ravenous, are capable of devouring, and they may form some idea of the appetite … of Tarrare."