When business tycoon Damien Hale (played by Ben Kingsley) faces death from cancer in Self/Less, in theaters today, he doesn’t go gently into that good night. Instead, he undergoes a radical underground medical procedure called “shedding” that allows him to transfer his mind into another, younger, healthier, lab-grown body (Ryan Reynolds’s body, to be exact) and start a whole new life with a new identity.

For now, this is science fiction—but, says Charles Higgins, a neuroscientist at the University of Arizona, it could one day happen. “We cannot yet conceive of a machine that could scan the brain to the extent required to do what is in the movie,” he tells mental_floss. “But 100 years ago we could not conceive that in our pockets we would carry what are, essentially, supercomputers and communicators that we can talk to anyone on the planet with.”

Studying the brain is Higgins's business. “I’m interested in the interface between the mind and the brain and quantifying things that are normally unquantifiable, like depression, mood, consciousness, and self,” he says. Among the things he and his team are working on in his lab: grabbing electrical signals from insect brains to build high-tech robots with excellent vision; figuring out how cognition works by creating a simulated, computerized rat that wanders around a digital maze; and gathering data on human sleep with a device he built. So though he didn’t consult on Self/Less during production—the studio brought him on afterward—he’s an excellent source to talk to about the film’s science.

According to Higgins, there are huge hurdles to jump before we transfer consciousness from one body to another. For one, there’s a lot we don’t understand about how the brain—and consciousness in particular—work. “If you ask 100 different experts to list what the brain does, you’ll get 100 different answers,” Higgins says. “The brain definitely regulates your life support. Sometimes we use the word cognition—is that what the brain does? It’s a memory system as well. You could go on and on.”

Once we understand the brain in the same way we understand the heart or a computer, Higgins says, “we’ll be able to see how brains are related and understand what the important details we need to get out of the brain are.”

Another challenge: Computers have software, but the brain isn’t quite so simple. “The software and the hardware are all [together],” Higgins says. “So what details of the brain structure do I need to read out?”

Some people, he says, think we need to go down to a quantum level. Others think it might be unnecessary to go subatomic to scan consciousness: “You could go just to the level of of neurons and other connections,” Higgins says. “But we don’t really know.”

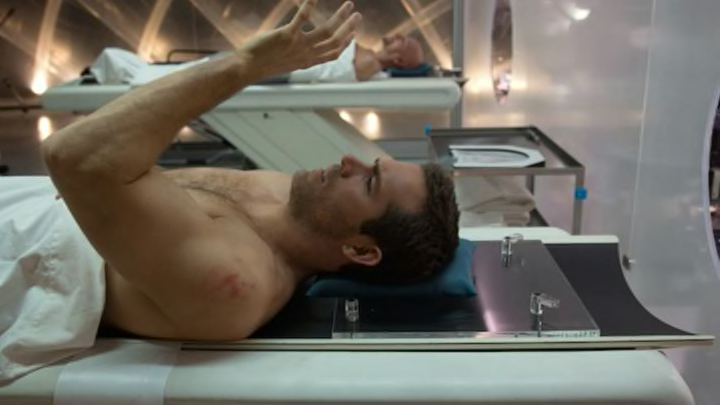

Even if we did know where consciousness was found, we don’t have the technology to transfer it. In Self/Less, the company Phoenix Biogenic uses what looks like a souped-up fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to access and transfer consciousness from one body to another. Higgins says this is “the right idea, although at this point fMRI technology does not allow us to get down to sub-neuron resolution.”

And then there are the thorny ethical issues. When Hale discovers that he hasn’t been given a lab-grown body after all, but the body of a man who once had a life of his own, he’s disgusted and outraged and not entirely sure what to do.

“Scanning somebody’s brain and putting it into another body—you have to wonder, did you destroy someone’s self to do that?” Higgins says. “Let’s say you cloned me and grew me until I was 20 years of age, and then you transferred [my consciousness] into my new, younger body. Was the 20-year-old clone a person of its own? Did it have a self, a soul, an inherent value of its own? Did I kill someone?”

Uploading a consciousness to a computer will likely come first, “because the ethical issues are almost nonexistent,” he continues. “Scanning something into a computer isn’t going to hurt anybody.”

Of course, whether you’re talking about computerized consciousness or body hopping, it’s all hypothetical for the moment. But if and when we do get there, there’s more could do more than merely swap older bodies for younger models. Higgins foresees a future where we can talk to computer copies of the greatest scientists who ever lived, or instantly upload to our brains an education that would otherwise take 10 years to complete.

“If you could actually do this, what impact would it have on society?” he asks. “What if everybody understood world history? Could American citizens be better informed—make better decisions, work together, support our congress and our president rather than having a bunch of different uninformed opinions? What if everyone was an expert engineer and knew how to work their newfangled TV sets? Life would be different. Would it be more pleasant? Maybe you’d spend less time being frustrated by politics and electronics and anything else you’d want to learn about. Or maybe it would create an even worse have and have not situation. It’s a very difficult thing to say.”

We may be very, very far from the future as imagined by Self/Less, but that doesn’t mean we’ll stop looking for it. Humans have been searching for immortality for as long as we’ve been around. “We’ve all felt that when somebody died that something was lost, either just to us or to the world,” Higgins says. “That’s been around as long as humankind, and I don’t see that going away. That will drive technological development for however long it takes until this is possible.”