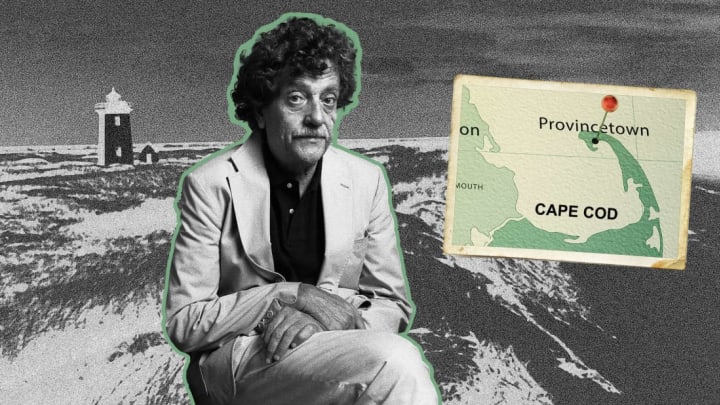

Kurt Vonnegut became a bestselling author and a household name with the publication of his sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, in March 1969. The book was inspired by his experience as a POW during the Allied bombing of Dresden, and explores themes of war, violence, and death. Throughout his life and career, Vonnegut returned to these subjects over and over again—in his novels and short stories, in his essays, and in his nonfiction writing and reporting.

Perhaps it was his obsession with these dark themes that made Vonnegut so fascinated with 24-year-old Antone “Tony” Costa, a.k.a. the Cape Cod Cannibal, a serial killer notorious for the brutal murders and dismemberment of at least four women in and around the town of Truro, Massachusetts, in the late 1960s. That, and the terrifying true fact that Vonnegut’s daughter Edith met and became acquaintances with Costa during a summer stay on Cape Cod.

Could she have become one of the Cape Cod Cannibal’s victims? The thought crossed Vonnegut’s mind more than once.

Tony Costa’s Terrible Crimes

At the height of the counter-culture movement of the 1960s, Provincetown was something of an oasis for the nonconforming individuals who defined the decade’s social upheaval. Its picturesque setting and free-spirited vibe drew artists, dreamers, and free thinkers from all over the country—often to the dismay of older local residents, who bristled against the bohemian lifestyle and everything that came with it. They feared that the counter-cultural ways of the young people flocking to their shores would bring their town nothing but trouble.

Little did they know that the trouble they faced actually came from within.

As the end of the decade approached, young women—some native to the area, others just passing through—started going missing from Provincetown and the neighboring town of Truro. The first was Sydney Monzon, a local who vanished in May 1968. Then Susan Perry, a troubled teen with a history of drug use, disappeared in September of the same year.

Teen runaways were common at the time, so no one in the community was that surprised or alarmed when the girls went missing. But when Patricia Walsh and Mary Anne Wysocki, two women in their twenties visiting Provincetown for the weekend, disappeared in January 1969, authorities became suspicious. Unlike Monzon and Perry, Walsh and Wysocki were regarded as “good girls” who wouldn’t run away from their families or their stable lives.

Two weeks after their disappearance, the women’s car—a Volkswagen—was spotted in Truro Woods, but it quickly vanished. Police and detectives searched the area where the car had been seen, only to discover something they never expected: the mutilated body of Susan Perry. Further searches of the area would lead authorities to unearth the remains of Monzon, Wysocki, and Walsh. All three bodies were dismembered.

Shortly after the grisly discovery, local carpenter Tony Costa was arrested on murder charges. Costa was known to grow marijuana in the woods where the bodies were found, and he had been seen driving the missing Volkswagen—but he insisted on his innocence, alternately blaming the murder on friends and people he made up. (He would later write about the murders in a novel, Resurrection, which was never published, and reveal further details of the crimes through hypnosis.) Although many townsfolk thought Tony, who had a reputation as a thief and a drug user, was an odd character, they never believed he could be a murderer.

It didn’t take long for the media to give Costa the headline-worthy nickname “Cape Cod Cannibal,” after district attorney Edmund Dinis told the press that the “hearts of each girl had been removed from the bodies,” and that there were teeth marks found on the victims. Never mind that those things weren’t true—his comments, and reports that the bodies showed signs of necrophilia, drew national attention to the case, and rattled the Cape Cod community, which was appalled to learn a serial killer had been living among them all that time.

In May 1970, Costa was found guilty of the murders of Mary Ann Wysocki and Patricia Walsh, and sentenced to life in prison. Although he was only ever linked to the bodies of the four women buried in Truro Woods, it’s believed he killed up to eight victims.

Writing About—And To—A Killer

Vonnegut—who had moved to Cape Cod in the early 1950s—wrote about Costa and his crimes in a 1969 essay for LIFE (later reprinted in his collection Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons). He compared Costa to Jack the Ripper, discussed the victims and what Costa did to them (“the details are horrible and pitiful and sickening”), and explored Costa’s personal life and his connection to Cape Cod’s hippie culture.

But what Vonnegut seemed most interested in was his own connection to Costa, and the fact that his daughter had met the man—and even been friendly with him.

“My 19-year-old daughter Edith knows Tony Costa,” Vonnegut wrote in the piece, titled “There’s A Maniac Loose Out There” (a phrase uttered by Costa himself). “She met him during a crazy summer she spent on her own in Provincetown, knew him well enough to receive and decline an invitation he evidently extended to many girls: ‘Come and see my marijuana patch.’”

It was near this marijuana patch in Truro that the serial killer hid his victims in shallow graves. Costa had also killed at least two of his victims, Walsh and Wysocki, there.

Luckily, Edith never took Costa up on his offer, but it wasn’t because she thought he could be dangerous—Edith believed Costa was strange but harmless. Most of the area residents did, too. Despite his run-ins with the law and heavy drug use, Costa was well-liked by many in the community, especially children. He was a fun and friendly babysitter to the local kids whose parents were either too busy or too apathetic to care for their kids during the hot and hectic days of summer.

Which is why so many area residents were shocked to find out Costa was a cold-blooded killer, including Edith. “‘If Tony is a murderer, then anybody could be a murderer,’” Vonnegut reports Edith told him during a phone conversation.

After writing about the murders for LIFE, Vonnegut struck up a sort of correspondence with the imprisoned Costa. “The message of his letters to me was that a person as intent on being virtuous as he was could not possibly have harmed a fly,” Vonnegut wrote in the essay “Embarrassment,” which appeared in his 1981 collection Palm Sunday. “He believed it.” Costa died by suicide in prison in 1974.

Finding Inspiration in the Cape Cod Cannibal

Though his daughter provided Vonnegut a direct connection to the killer, he wasn’t the only author to become interested in Costa’s crimes. Leo Damore published a book about Costa, called In His Garden, in 1981. Novelist and Provincetown resident Norman Mailer was said to be fascinated with the case, and even used it as inspiration for a novel: 1984’s Tough Guys Don’t Dance, a story about an ex-drug runner and the decapitated head of a woman he finds in his marijuana patch in the woods. It was adapted into a film in 1987 that Mailer himself directed. (Unfortunately for the author, both the novel and the movie were met with mediocre reviews.)

As true crime has become more popular than ever, there has been renewed interest in the Cape Cod Cannibal from the book world, Hollywood, and beyond. Journalist and The Finest Hour author Casey Sherman is currently working on Helltown, a novel about Vonnegut and Mailer’s interest in the case, that is due to be published later this year. In January, Team Downey, the production company helmed by actor Robert Downey Jr. and his wife Susan, acquired the rights to Sherman’s forthcoming novel, with plans to turn the book into a TV series.

But perhaps the project that gives the best look at Costa is The Babysitter, a memoir from author and former Provincetown resident Liza Rodman, co-written with Jennifer Jordan, which chronicles her summers spent with the serial killer—though she didn’t know Costa was a murderer until much later. “A lot of adults we knew just didn’t want anything to do with children,” Rodman told the New York Post. “Tony was not like that. He seemed to really like being with us. He never yelled. He was really gentle. … The person I knew certainly was not the person I researched.”