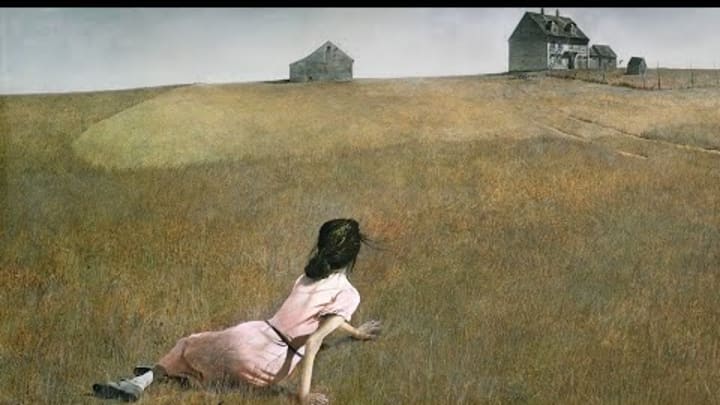

Who is the woman in Andrew Wyeth's striking painting Christina’s World, and why is she sprawled in a field, looking longingly toward a far-off farmhouse? For decades, these questions have drawn in viewers, but the true story behind Christina’s World makes the 1948 painting even more intriguing.

- There was a real Christina.

- Olson’s spirit inspired Wyeth’s most popular piece.

- Pages and pages of sketches preceded the painting.

- Olson was not the painting’s only model.

- The farmhouse depicted in Christina’s World is a real place.

- Christina’s World was one of several paintings Wyeth did of Olson.

- Christina’s World was met with little fanfare.

- Wyeth was initially unhappy with Christina's World.

- Nonetheless, Christina's World found a major supporter.

- Christina’s World was Olson's favorite Wyeth painting ...

- ... And it made her famous.

- The painting’s place in the art pantheon is still a matter of debate.

- MoMA has only loaned out Christina's World once.

- Wyeth is buried near his painting’s birthplace.

- Today, the Olsen house is a national landmark.

There was a real Christina.

The 31-year-old Wyeth modeled the painting’s frail-looking brunette after his neighbor in South Cushing, Maine. Anna Christina Olson had a degenerative muscular disorder that prevented her from walking. Rather than use a wheelchair, Olson crawled around her home and the surrounding grounds, as seen in Christina’s World.

Olson’s spirit inspired Wyeth’s most popular piece.

The neighbors first met in 1939 when Wyeth was 22 and courting 17-year-old Betsy James, who would later become his wife and muse. It was James who introduced to Wyeth to the 45-year-old Olson, kicking off a friendship that would last the rest of their lives. The sight of Olson picking blueberries while crawling through her fields “like a crab on a New England shore,” as Wyeth put it, inspired the artist to paint Christina’s World.

“The challenge to me was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless,” he wrote. “If in some small way I have been able in paint to make the viewer sense that her world may be limited physically but by no means spiritually, then I have achieved what I set out to do.”

Pages and pages of sketches preceded the painting.

Wyeth was obsessed with getting the position of Christina’s arms and hands just right. Today these sketches are tenderly preserved for posterity.

Olson was not the painting’s only model.

The concept, title, pink dress, and slim limbs were modeled after Olson, who was in her mid-fifties when Christina’s World was created. But Wyeth asked his then 26-year-old wife to sit in as a model for the head and torso.

The farmhouse depicted in Christina’s World is a real place.

It was Olson’s home, which she shared with her younger brother, Alvaro. But Wyeth took some liberties with its architecture and surrounding landscape to better emphasize the scope of Christina’s journey.

Christina’s World was one of several paintings Wyeth did of Olson.

She was a recurring muse and model for Wyeth, captured in paintings like Miss Olson, Christina Olson, and Anna Christina.

Christina’s World was met with little fanfare.

Wyeth’s timing wasn’t quite right: He finished the painting in 1948, which meant the magical realism masterpiece debuted at a time when Abstract Expressionism was all the rage.

Wyeth was initially unhappy with Christina's World.

Though it would become his best-known work and an icon of American art, Christina’s World was described by Wyeth as “a complete flat tire” when he sent it off to the Macbeth Gallery for a show in 1948. He also wondered if the painting would have been improved if he “painted just that field and have you sense Christina without her being there.”

Nonetheless, Christina's World found a major supporter.

Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, was so taken with Wyeth’s work that he purchased Christina’s World for $1800. While the early critical reception was lukewarm to cool, the painting’s prestigious position at MoMA fortified its reputation. Today, it’s one of the museum’s most admired exhibits.

Christina’s World was Olson's favorite Wyeth painting ...

One person who didn’t object to Wyeth’s depiction of Olson was Olson. In her book about her husband’s work, Betsy James Wyeth recounts a conversation she had with Olson about the piece, writing: “Christina’s World remained her favorite to the end. Once when I asked her why, she simply smiled and said, ‘You know pink is my favorite color.’ ‘But you’re wearing a flowered pink dress in Miss Olson and holding a kitten. I thought you loved kittens.’ “Course I do, but in the other one Andy put me where he knew I wanted to be. Now that I can’t be there anymore, all I do is think of that picture and I’m there.’ ”

... And it made her famous.

Shortly after the painting made its MoMA debut, one overzealous admirer walked into Olson’s home, came upon her resting, and asked for an autograph. Twenty years later, her death made national news, reviving interest in Christina's World.

The painting’s place in the art pantheon is still a matter of debate.

Though undeniably iconic, the painting has long been undermined by vocal detractors. Art historians have often snubbed Wyeth’s works in their surveys, and some naysayers have attacked the painting's widespread popularity, deriding it as “a mandatory dorm room poster.” Meanwhile, critics have chastised Wyeth’s attention on Olson’s infirmity and characterized it as exploitation. Still others claim there was no art in rendering realistic imagery in paint.

MoMA has only loaned out Christina's World once.

Following Wyeth’s death in 2009 at the age of 91, the museum allowed Christina’s World to visit its creator’s birthplace, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where the Brandywine River Museum exhibited the polarizing painting for two days in memorial before returning it to New York.

Wyeth is buried near his painting’s birthplace.

Down the hill from the Olson house lies a cemetery, where Andrew Wyeth’s grave can be found in the family plot of Alvaro and Anna Christina Olson. Wyeth’s tombstone faces up toward the house at an angle that closely resembles that of Christina’s World. According to his surviving family, it was his final wish “to be with Christina.”

Today, the Olsen house is a national landmark.

The Olson house has won comparisons to Monet’s garden at Giverny because of the plethora of paintings and sketches it inspired. In the 30 years from their first meeting to Christina’s death, Wyeth created over 300 works at the Olson house, thanks to the Olsons allowing him to use their home as his studio. Explaining the house's hold on him, Wyeth said, “In the portraits of that house, the windows are eyes or pieces of the soul almost. To me, each window is a different part of Christina’s life.” For all this, the Olson House was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2011.

Discover More Facts About Famous Artworks:

A version of this story ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2024.