In true, iconic fashion, the persona of Rosie the Riveter preceded the person. There was no single Rosie, actually, but several—and two in particular who shaped the legendary image we now associate with all the American women who worked factory jobs during World War II, and bolstered both the war effort and their own economic and social power in the process. Unlikely as it may seem, the story begins with a song.

The character was first mentioned by name in a 1942 tune called “Rosie the Riveter” by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. The song quickly gained popularity and was played by many big bands of the day, most notably one led by Kay Kyser. It tells the story of a woman working in a factory during wartime.

All the day long whether rain or shine She’s a part of the assembly line She’s making history, working for victory Rosie the Riveter Keeps a sharp lookout for sabotage Sitting up there on the fuselage That little frail can do more than a male will do Rosie the Riveter

After the tune became a hit, Rosie came to represent the millions of women who had joined the industrial labor force. The U.S. government used Rosie as a propaganda tool, a symbol of civic duty, and a vehicle to glamorize enlisting in the effort.

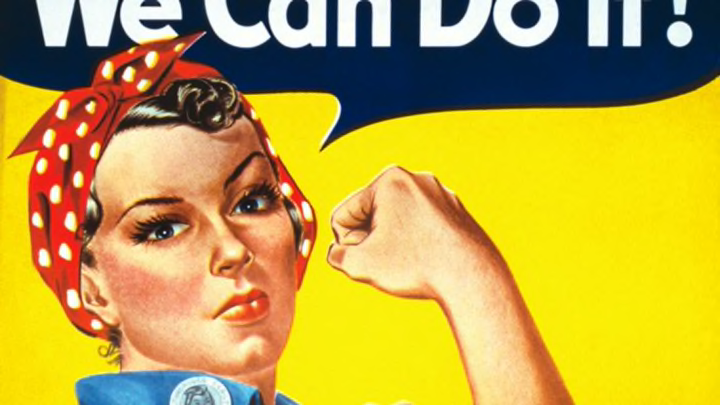

WE CAN DO IT!

The Rosie we most readily call to mind today is the work of J. Howard Miller, a Pittsburgh artist who was hired by the Westinghouse War Production Coordinating Committee to make a series of upbeat posters for its buildings in 1942.

Miller found his inspiration for the “We Can Do It!” poster from Geraldine Hoff Doyle, a 17-year-old metal-stamp presser at American Broach and Machine Co. in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who was snapped by a wire service photographer while working in a (now iconic) polka dot bandana. Doyle left that job two weeks later to work at a soda fountain and went four decades without knowing she was the basis for the powerful, bicep-flexing Rosie in Miller’s poster. Miller’s image was only on display in the Westinghouse factory for two weeks in 1942, and the powerful woman was never specifically called “Rosie” (how the poster became known as Rosie is a bit of a mystery).

As the Rosie character’s propaganda role grew, real life Rosies entered the narrative: In 1944, actor Walter Pidgeon discovered Rose Will Monroe, a riveter at the Willow Run Bomber Plant in Ypsilanti, Mich., and recruited her to star in a film promoting the sale of war bonds. Rose Bonavita was a riveter at he General Motors Eastern Aircraft Division in North Tarrytown, N.Y. She set a record by driving 3345 rivets in an Avenger torpedo bomber during a single overnight shift and received a commendation letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Through it all, Doyle remained oblivious to how she had inspired Miller’s poster. When the Rosie image resurfaced as part of the feminist movement in the 1980s, Doyle finally learned about the role she had passively played in winning World War II.

It’s somewhat unclear how this particular piece of artwork rose to prominence; according to some reports, Miller’s image was rediscovered in the U.S. National Archives in 1982. It appeared that same year in a Washington Post article and on the cover of Smithsonian magazine in 1994.

From there, Doyle’s likeness became synonymous with powerful women, and while she did have a chance to see the meteoric second rise of the “Rosie” image before passing away in 2010, she told the Lansing State Journal in 2002, "It's just sad I didn't know it was me sooner."

The Other Rosie

Doyle wasn’t the only artistic Rosie who inspired American women to keep up the industrial fight. During World War II there was another famous depiction of Rosie, this one based on Mary Doyle Keefe, a 19-year-old telephone operator and neighbor of painter Norman Rockwell. He painted Keefe as Rosie the Riveter in 1943, one year after Miller’s Rosie posters went into circulation. Rockwell’s Rosie ran on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, complete with quite a bit of artistic license—Rockwell transformed the petite Keefe into a strapping, musclebound Rosie holding a rivet gun on her lap and using a copy of Mein Kampf as a foot rest. While Miller’s “We Can Do It!” poster was largely unseen at this point, by the time Rockwell depicted his riveter with a lunch pail emblazoned with “Rosie,” the character was well on its way to becoming entrenched in the American psyche.

"Other than the red hair and my face, Norman Rockwell embellished Rosie's body," Keefe said in a 2012 Hartford Courant interview. "I was much smaller than that and did not know how he was going to make me look like that until I saw the finished painting."

While she did experience a bit of teasing after the issue hit newsstands, Keefe said she didn’t mind much. “It didn't bother me. I was slim and trim,” she told the Courant in 2001. “Just the idea of being able to sit for Norman Rockwell was a nice thing to do.” Rockwell had told her ahead of time that she probably wasn’t going to like the painting, which he styled after Michelangelo's depiction of the prophet Isaiah in the Sistine Chapel.

Keefe received $10 for her two mornings of modeling work. Twenty-four years later, she received a second bit of compensation: A letter from Rockwell apologizing for the burly depiction.

“The kidding you took was all my fault,” he wrote, “because I really thought you were the most beautiful woman I had ever seen.”

The painting would later be used by the U.S. Treasury Department to help sell war bonds. Keefe died last week at age 92.

Given Rockwell’s status as a titan of Americana painting, how did Miller’s poster become the definitive depiction of Rosie? Thank copyright law. Rockwell’s image was copyrighted, while Miller’s poster was not, clearing the way for it to become a phenomenon.

It’s fitting that the true story of Rosie isn’t actually about one woman, given how it’s taken on a new life to represent something universal. Keefe and Doyle remain intertwined through a name, and a legacy. Although neither woman actually worked as a riveter, both represented their generation and—perhaps to everyone’s surprise—many generations since.