Globalization has given us such incongruous cultural mash-ups as the Hindu-friendly Big Mac and Bulgarian Music Idol, but perhaps nowhere in the world has the interaction between foreign cultures been so fruitful as in Japan. The rise of English as the global tongue has created a whole new subset of language in the Land of the Rising Sun, a sort of fusion of English and Japanese called wasei-eigo (which actually means “made-in-Japan English”). These are words with English roots that have been so thoroughly Japan-ized as to be rendered barely recognizable to native English speakers. So for those hoping to “level-up” (there’s some wasei-eigo for you) their communication skills before traveling to Tokyo, consider memorizing these Japenglish gems.

1. “Baiking”

If you eat in Japan, chances are you’ll come across a restaurant advertising a baiking (“Viking”) lunch. But you won’t find customers wearing horned helmets and dining on the spoils of war—baiking just means a buffet. The story goes that Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel was the first in Japan to serve buffet meals, and their “Viking smörgåsbord” (which was in turn named after the Kirk Douglas adventure film The Vikings) caught on as the name for everyone’s favorite way to all-you-can-eat.

2. “Donmai”

It sounds like it should mean “I don’t mind,” but donmai actually comes from the clunky English reassurance, “Don’t pay that any mind,” i.e., “Don’t worry about it!” In other words, “Your fugu sashimi’s poisonous? Donmai.”

3. “Maipesu”

In Japan’s hyper-speed, group-oriented society, doing something at one’s own pace isn’t exactly an accolade. Which is why the term maipesu (“my pace”) is used somewhat pejoratively to describe someone who dances to the beat of their own drummer or does their own thing. For example, “Yoko Ono is so maipesu.”

4. “Wanpisu”

You can probably guess that wanpisu comes from the English term “one piece.” But if the sentence, “My cousin’s wedding was beautiful, the bridesmaids all wore lovely one-pieces,” has you imagining a row of ladies posed in matching swimsuits, think again—wanpisu is actually the Japanese word for a woman’s dress.

5. “Handorukipa”

For a wild night out, a handorukipa is a necessity. That’s because Japan has a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to drinking and driving—so you’d better hope your buddy is willing to be the “handle keeper” (i.e., designated driver).

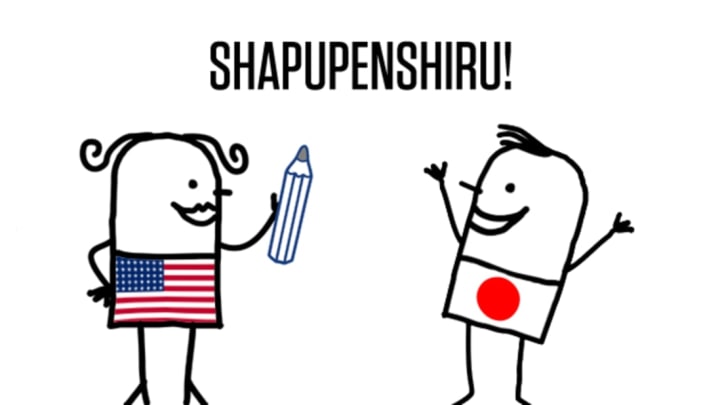

6., 7., and 8. "Konsento," "Hochikisu," and "Shapupenshiru"

Don’t be alarmed if your Japanese co-worker comes to you asking for konsento (“consent”). This just means they want to use your “concentric plug,” i.e., your power outlet. Same goes if they’re looking for a hochikisu (“Hotchkiss”), which means stapler, so named because the E. H. Hotchkiss Company was the first to produce the office staple (pun intended) in Japan. And if they ask for a shapupenshiru (“sharp pencil”), toss ‘em a pencil of the mechanical variety.

9. and 10. “baiku” / “bebika”

Shock your Japanese friends by telling them that you spent all weekend teaching your 5-year-old daughter how to ride a bike. In Japan, baiku means motorcycle. Likewise, if a toddler goes out for a spin in the bebika (“baby car”), they’re merely riding in a stroller.

11. “romansugurei”

Rather than Japanese Fifty Shades of Grey fan fiction, “romance grey” actually describes the Anderson Coopers and Richard Geres of the world. Think a handsome older gentleman with grey hair, or what we’d call a “silver fox.”

12. “manshon”

Don’t expect too much if a Tokyoite invites you over to their “mansion”—you won’t find marble floors or an indoor pool, because manshon simply describes a condominium-style apartment complex. (‘Cause good luck trying to fit a real mansion in Tokyo.)

Most Japanese people are surprised to find out that a perfectly grammatically-correct sentence like, “I got wasted at the viking, but luckily the handle keeper will gimme a ride back to my mansion,” sounds like gobbledygook to the average English speaker. But not everyone has embraced the widespread use of wasei-eigo. In fact, one 72 year old man recently made headlines when he sued the Japanese national public broadcaster because he couldn’t understand their Japanenglish-riddled programming. (Thus, he claimed, causing him 1.41 million yen worth of emotional distress.) He lost—which makes you wonder whether, after delivering the verdict, the judge told him, “Donmai.”