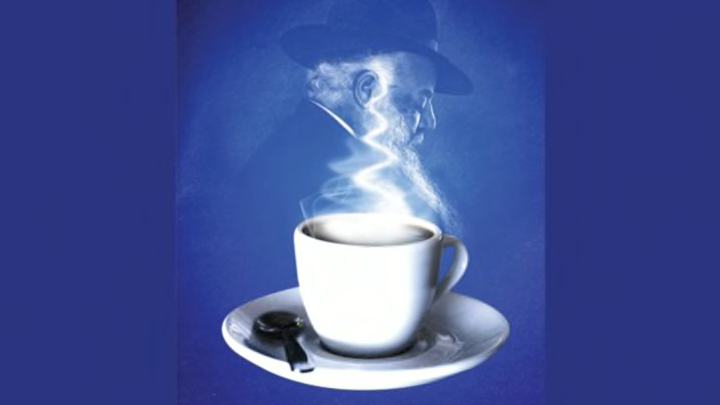

As Maxwell House stormed into American coffeepots in the early 1920s, the company ran into a stubborn subset of holdouts. During Passover, Ashkenazi Jews are forbidden from consuming beans and other legumes. Since everyone thought of coffee as a bean, a big part of the Jewish population swore off their daily Maxwell House during Passover.

Enter marketing whiz Joseph Jacobs. As the architect of Maxwell House's advertising campaigns, he enlisted the help of a New York rabbi, who in 1923 made the botanically sound proclamation that coffee "beans" were actually just dried berries. Since dried berries are kosher for Passover, Jewish coffee drinkers no longer had to choose between morning drowsiness and heresy.

Nine years after the landmark kosher ruling, however, Passover sales still lagged. Jacobs responded even more aggressively. Passover seders follow a text called the Haggadah that tells of the Jews' exodus from ancient Egypt. In 1932, Jacobs had a simple idea: What if Maxwell House printed its own version of the Haggadah and gave it away with coffee? The idea was good to the last drop. Over eight decades later, there are over 50 million copies of the Maxwell House Haggadah in print, including a gender-neutral translation in 2011. The White House even uses it in its seder! Who knew the famous blue can was so pious?