Even prospectors and cowboys need to keep up with their correspondence. In the mid-19th century, there was no transcontinental telegraph line, and as California’s population approached 400,000 with a civil war looming, waiting weeks or months for cross-country mail (by ship or stagecoach) was more than annoyance—it was a real problem.

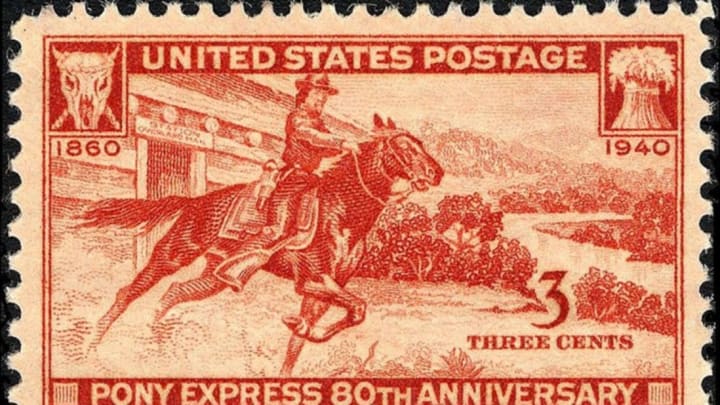

Enter the Pony Express, whose first rider hit the trail on this day in 1860. Financial struggles ended the storied service’s operations after just 18 months, but even though it failed as a business, it became one of the great legends of the Wild West.

The Early Days

The Pony Express—an offshoot of a company called Leavenworth & Pike's Peak Express Company—was founded by William H. Russell, Alexander Majors and William B. Waddell in response to a scaling back of mail service to California. At the time, Postmaster General Joseph Holt said, “Until a railroad shall have been constructed across the continent, the conveyance of the Pacific mails overland must be regarded as wholly impracticable”—a truth that the three founders of the Pony Express would later be forced to accept.

The First Ride

On April 3, 1860, the very first rider (whose identity is disputed) took off from St. Joseph, Missouri at 7:15 p.m. with 49 letters, five telegrams, and various other papers in a custom-made mochila saddle cover. Cannon fire signaled the beginning of his journey and his impending arrival at the Missouri River where a ferry was waiting. Around 10 days and nearly 2000 miles later, he reached Sacramento, Calif., where another rider had started out on the eastward route at the exact same time. That journey took a little longer—11 days and 12 hours—and while that might seem like a snail’s pace today, these test runs were a huge success. The Pony Express was on the move.

Up and Running

Getting a piece of mail from the Midwest to the Golden Coast in 10 days was an amazing convenience, but it came at a hefty price. A half-ounce piece of mail would set you back $5, which was a pretty penny just to say hello. The riders were compensated well for their labor, getting around $25 a week for carrying up to 20 pounds of mail. Neither men nor horses carried one load the entire way. Riders changed every 90 to 120 miles and horses every 10 to 15 miles. The Pony Express would eventually operate out of 186 stations, with 80 riders and some 400 horses transporting mail through what is now Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada. Despite the treacherous route and frequent transfers, only one mail delivery was ever lost.

The system could move at an even more rapid pace when it needed to. In November 1860, riders delivered the message of Abraham Lincoln’s election from Nebraska to California in five days, setting the record for fastest delivery via Pony Express.

Return to Sender

When they conceived the idea for the Pony Express, Russell, Majors, and Waddell had hoped to eventually sign a contract with the U.S. government, but their optimism was quickly extinguished. Two short months after the first historic ride, Congress passed a bill to help fund the transcontinental telegraph line connecting Missouri to the west coast which would, in turn, connect the entire country.

A Final Blow

In March of 1861, the government signed a contract with “Stagecoach King” Jeremy Dehut who ran the Butterfield Overland Mail Stage Line. Dehut acquired Pony Express stations for his stagecoach route. The contract was a fatal hit to Russell, Majors, and Waddell’s business model, and the Pony Express served a truncated route from Salt Lake City to Sacramento for its last few months of existence.

End of the Line

When the final connection on the Pacific Telegraph line was made in Salt Lake City on October 24, 1861, the Pony Express’s fate was sealed. The last of the 35,000 letters the service carried were delivered in November, and the Pony Express terminated with its three founders near bankruptcy.

The Kindness of Nostalgia

The news wasn’t all bad for the first mail service in the West. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody—who claimed to have ridden for the Pony Express at age 14—helped inflate the service’s legend through his autobiographies and popular Wild West Show. His remembrances helped to bolster the legend of the Pony Express, captivating American audiences with the romantic notion of a team of riders galloping out toward the coast, carrying with them the stories that mattered to a new generation of American trailblazers.