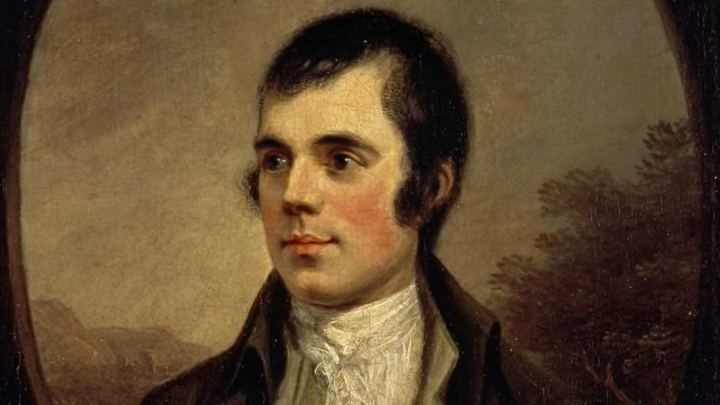

On January 25th, admirers of 18th-century poet Robert Burns toast the birthday of Scotland’s greatest bard over a Burns Supper, a meticulously planned affair of haggis, recitals, singing, and ample flowing of whisky—that perennial source of poetic inspiration. Yet proper appreciation of the poet and his works deems one venture beyond the New Year favorite “Auld Lang Syne.”

Polish up on this list of smirk-inducing words and phrases from Burns’s complete works below. Highlighting the imagination of his Scots language (a close cousin to English thriving in Scotland during his time), they are ripe for revival by Robbie revelers old and new.

1. Swankies

A nominal form of the modern adjective swanky, Burns penned this playful term to describe swaggering, strapping fellows in their prime. In “The Holy Fair,” Burns tells of "there swankies young ... springing owre the gutters" toward barefoot lasses.

2. Cantie (or Canty)

In his notes, Burns’ song titled “Contented wi’ litt’e, and cantie wi’ mair” is to be played to the tune of “Lumps o’ Puddin.” With a name like that, the feeling roused by this tune would sum up canty’s definition: excess of good spirit to the point of bursting into song. It’s this spirit that hosts of Burns Suppers strive for, and the song title distills the Ploughman Poet’s philosophy toward life in general.

3. Crouse

This mischievous-sounding verb was translated into the English of the day as “cocksure” as well as “jauntily.” This adjective is not to be used lightly. For the fleet of tongue, alliterate with the above as “crouse and canty,” as Burns did in “Duncan Gray,” for compounding affect.

4. Gawsie

A bold combination of large as well as jolly, Burns penned this adjective in reference to a dog's upward wagging tail. After a few drams of whisky, one may contrive some bawdier applications.

5. Fouth

There is some scholastic dissent as to the origins of fouth, a noun meaning fullness or abundance. It is generally agreed to be from the English full, as Shakespeare’s spilth derives from spill. However, some point to another possible derivation from Chaucer’s fother (a full load), in the manner food derives from fodder. Where lineage confounds, use in the context of drink is certain to avoid potential faux pas.

6. Donsie

“Tho' ye was trickle, slee and funny, Ye ne'er was donsie,” Burns once wrote of his auld mare. Described as saucy, testy, or poor mannered, this adjective may also find application among supper company.

7. Link

In “Address to the De’il,” one could get a negative connotation as Burns sends ol’ Clootie linkin’ home. However, this verb can also carry a merry, drunken air: a happy send-off to Burns Night revelers who’ve tippled out, and thus will trip totteringly along back home.

8. Blether

This phrase, meaning "to utter nonsense," is similar to its English cousin “blather,” and can often bely a pejorative tone—but it carries more complexity. It was taken up more innocently in 2014’s Scottish vote for independence in “Blether Together,” a phone drive program playing off union advocates’ slogan “Better Together” to encourage homely chats about voters’ concerns. When necessary, it can still be interjected to stop long-winded supper guests mid-blethering.

9. Eldritch

Possibly derived from an Old English term for “otherworldly,” or possibly connected with elves, Eldritch remains in parlance to the modern day, often to describe sounds. Burns wields it in his ghostly poetic tale of "Tam o' Shanter." When Tam is discovered spying on the devilish happenings at an auld haunted church, he is pursued by a "hellish legion" and makes his escape over the river Doon on his terrified steed, away from many an “eldritch skriech and hollo.”

10. Haughty Hizzie

Only the most familiar and literary of supper guests will forgive this phrase its Victorian era baldness as regards the fairer sex. A product of its time, this scalding phrase describes an indignant, unforgiving woman of crude makings.

11. Bickering Brattle

Always a deft alliterator, this turn of phrase appears in “To A Mouse,” where Burns laments upturning a nest of an innocent mouse. Bickering Brattle describes its quick, indecisive scurrying while evoking the action through onomatopoeia. Legend has it he composed the poem on the spot, plough still in hand—an impressive feat indeed given tongue-twisting arrangements such as this.

12. Gash

An adjective describing something wise in a manner belying prudence and prosperity. Burns employed this descriptor for the plaughman’s collie in ”the Twa’ Dogs,” drawing contrast against a gentry-raised dog in a sharp social allegory. One may find ways conveying this folksier sort of knowledge lacking today.

13. Jauk

To jauk is to trifle or dally in silly matters. After a rendition of Burns' “To A Mouse,” where Steinbeck drew inspiration for the famous title Of Mice and Men, one might muse whether all life isn't just a jauk?

14. Reck the Rede

A weighty phrase meaning "to heed advice given," its appearance in the last lines of “Epistle to A Young Friend” perfectly concludes any ceremonious diatribe, this list included.

“May prudence, fortitude, and truth, Erect your brow undaunting! In ploughman phrase, "God send you speed," Still daily to grow wiser; And may ye better reck the rede, Then ever did th' adviser!”