By Arthur Holland Michel

The concrete and glass headquarters don’t look like much, the sort of personality-devoid architecture you could find in any office park. It’s clever camouflage for the cutting edge Willy Wonka-style labworks within.

I’ve been following the scent of International Flavor and Fragrances (IFF) in Hazlet, New Jersey, for 10 days now. There’s a rumor that one company is responsible for perfecting the distinctive formulas of both Drakkar Noir and Cool Ranch Doritos, and I think I’ve found it. Of course, no one here is going to confirm who’s on the company’s top-secret client list. What I do know is that, with a little badge flashing and credential dropping, I’ve finally found my way in. I’m not sure what I’ll be shown, but I’ve been told I can’t photograph any of it. I’m just here to sniff.

In the spotless, light-filled lobby, there’s a promotional video playing on a loop: a man in a space-age lab coat sticking a loaf of crusty bread into an aroma-capturing device. My nose immediately detects a hint of my first crush’s perfume—a certain citrus with floral notes—and I wonder if her scent originated here. IFF, a multibillion-dollar international corporation, has fingerprints everywhere as the designer of flavor and scent profiles of many of the most popular products on the market, from the fruity rush that dazzles your tongue as you rip the head off a gummy bear to the pine-forest freshness wafting from a freshly cleaned toilet bowl.

The scientists who work here harness natural scents and meticulously reproduce them for commercial use. And they’ve been doing it for a while—the company’s roots go back to 1889, when two residents of the small Dutch town of Zutphen opened a concentrated fruit juice factory. The enterprise grew consistently and benefited from a cunning 1958 merger with van Ameringen-Haebler, a prominent U.S. flavor and scent maker. Back in 1974, IFF scientists created a synthetic version of ambergris, otherwise known as dried whale vomit, long prized as an essential for perfumes. In the ’90s, the company blasted a rose into space just to see if it would smell different in zero gravity. (It did!) Today, I’m hoping to get a peek at the art and chemistry of creating a distinct aroma and find out how they turn all those smells into billions of dollars.

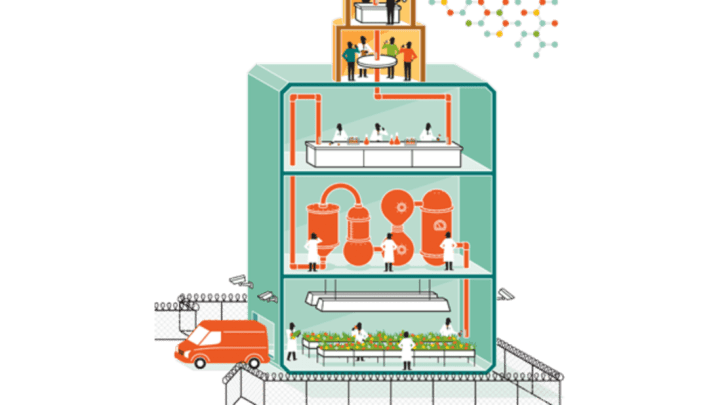

Past reception, the long, dreary hallway feeds into a lush tropical rainforest. Housing some 2,000 plant species, IFF’s greenhouse—one of several dozen such facilities worldwide—is massive and immaculately kept. The humidity here is intense. There are orchids everywhere. I can hear what sounds like a small river. I almost expect to look up and see a macaque swinging over my head. The director of IFF’s Nature Inspired Fragrance Technologies program, Subha Patel, guides me along. This is her operation. “Everything in here has an odor, and you should smell every one of them,” Patel tells me as she parts low-hanging branches to lead me deeper in. This workspace feels like the Amazon (I would know, having grown up in South America).

Patel is soft-spoken and warm. She tells me she’s been with IFF for nearly 37 years, groomed as a protégé of Braja Mookherjee, the IFF scientist who invented much of the technology the company uses to capture the scent of living things. As she talks, it’s clear she adores the plants she cultivates here. Although she has inhaled their blooms every day for decades, she still rel- ishes each aroma. At every step, she stops me. “Smell this,” she says, demonstrating the proper way to coax a plant into sharing its fragrance. She gently clutches its leaves, taking care not to crush them. Then, carefully letting them go, she raises her hand to her nose to take in the fragrance. “Smell this,” she repeats, a few paces later.

I sample a rare orchid from Madagascar labeled “white orchid” (one of Patel’s favorites), ylang-ylang (which smells like a musky animal), patchouli (“popular for men’s fragrances”), guava (which smells like stale cat pee or, as Subha puts it, “different and unique”). The most impressive is the chocolate flower, which could double for a Cadbury bar. It’s from these natural specimens that Patel and her team begin the work of creating an artificial smell or flavor.

IFF

Chocolate—or anything else—smells the way it does because it emits a specific combination of volatile chemicals. It’s part of Patel’s job to decipher exactly what those chemicals are. To capture the scent in order to study its chemical composition, she uses a process called solid-phase microextraction. That’s a fancy way of saying she places a jar over the object and inserts a thin strip of polymer into the glass to absorb the fragrance. This is a delicate process. Patel has to be careful to make sure that no other scents are sneaking in, though she admits that in nature it’s impossible to completely isolate any single aroma—she finds a certain romance in that. The jar system lets the scientists capture the scent of a plant without killing it. “The flower has a better aroma profile when it’s alive,” Patel says, handing me a twig of fragrant cinnamon.

From the greenhouse, the sample goes to the lab, where a team analyzes its chemical composition using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, a technique you might remember from high school chemistry. First, a machine separates the aroma into its component molecules. Every chemical is then ionized so that it gives off a particular electrical signal. With this data the scientists can see exactly what chemicals are present in the scent and in what proportion. A formula for jasmine, for example, might include methyl benzoate, eugenol, and isophytol. Meanwhile, a cinammony fabric softener will probably contain something called cinnamaldehyde, also known by the more tongue-tying name 3-phenylprop-2-enal.

Of course, plants are only part of IFF’s extensive scent palette. Beyond the greenhouse, the company has also re-created hundreds of living smells, including the aroma of horses, the musk of deer and civets, and the rich bouquet of freshly minted money (which some private clients request for custom perfumes). The technique can theoretically be used for anything: In 1997, IFF announced that it had captured the smell of a mountaintop. But what exactly is it doing with this vast library of scents?

I quickly learn that breaking down the natural scents is just the start. From the lab, an aroma is shipped off to the master artists of the fragrance world: the perfumers and scent design managers. They’re the ones who mix individual aromas, along with other aromatic chemicals, to create the scents that end up in your household sundries and cosmetics. If each smell Patel captures is like a single shade of paint, a finished fragrance is like a whole canvas. But creating an aroma for a cleaning product, for example, isn’t just a matter of making something that smells clean.

“We’re trying to make a tedious experience more interesting,” says Stephen Nicoll, a vice president and senior perfumer. Nicoll joins me, along with Deborah Betz, one of IFF’s keen-nosed scent design managers, in a large neutral-smelling conference room. (Nicoll and Betz experience the world nose first. They talk about fabric softeners the way sommeliers talk about fine wines. And they take pains to cleanse their palates—Nicoll says he takes a week- long smell vacation every year in a remote forest to give his nose a break.)

Creating a fragrance, I learn, is more than hard science: It’s also about psychological and emotional manipulation. Your sense of smell is different from the other physical senses. While the eyes and ears take information and route it through the thalamus before it goes to the parts of the brain that process and interpret it, the nose sends signals directly to the olfactory receptors, which lie in the limbic system, the part of the brain that processes emotions and memory. This is why the faintest whiff of a fragrance can teleport you instantly back to a specific time or place and trigger powerful emotions—like that indelible memory of my childhood crush.

The companies that make household products have a large stake in the specific emotions their items evoke. You’re not going to buy something over and over if it triggers an unpleasant feeling; marketers want you to feel comfortable and content so you become a loyal customer. So Nicoll and Betz’s job is to make sure that when you sniff your freshly pressed shirt each morning, you feel a manufactured nostalgia—the sort of specific, custom-ordered emotion your fabric softener brand wants you to feel.

In fact, IFF has trademarked its own scientific field: aroma science. In 1982, IFF collaborated with scientists at Yale University to carry out the first extensive studies on the effects odors have on human emotions. Within 10 years, researchers had made a number of remarkable discoveries, including the fact that a whiff of nutmeg can reduce a stressed person’s blood pressure. (Take that, pumpkin spice haters!) Peppermint, on the other hand, seems to be something of an aphrodisiac.

To measure a smell’s emotional impact, Nicoll and his team have volunteers sniff aromas in a controlled environment and then fill out a carefully worded questionnaire that measures responses like irritation, optimism, well-being, and arousal. Analyzing the participants’ responses, Nicoll can tell exactly which fragrance to add to, say, a fabric softener so that it makes the consumer feel “cuddly.” (The secret: notes of amber, a sweet, warm tone typically made from a mix of balsams like labdanum, vanilla, and fir.)

Another secret: Smells go in and out of style. So IFF takes pains to protect its billion-dollar interest and stay ahead of the curve. To gauge what’s fashionable, Betz and other IFF employees take “trend treks.” Recently, they visited stores and restaurants in New York to see which fragrances and foods are at the forefront. These days, it’s sea salt and cherry blossom, Betz says. And although it’s not advisable to eat your laundry, food scents are increasingly finding their way into home-care products. “Ten years ago,” says Betz, “you would never have thought to see a vanilla scent in a floor cleaner.”

If vanilla floor cleaner is what people want, Nicoll’s job is to give it to them. To avoid contaminating the tests, Nicoll and Betz aren’t allowed to wear perfumes and must wash their clothes with unscented detergents. Today, Nicoll is working on fabric softener, mixing the chemicals and essences Patel captured in the greenhouse. Like a composer, he assembles an olfactory symphony, a fragrance with more than 20 different chemicals. He puts the result onto a blotter, and the members of his team take a deep sniff. Nicoll shows me four drafts he worked on that morning. They are complex and abstract, not recognizable, and yet vivid, evocative, impressionistic; one in particular feels like the future. Like what the “new car” scent would smell like for a next-generation spacecraft.

Once a fragrance is created, it’s vigorously vetted. It gets passed between perfumers, scent design managers, representatives from the customer company, and test subjects—all together, hundreds of noses. And just because a senior perfumer thinks a scent delivers a “clean” feeling, it doesn’t necessarily mean everyday users will agree. So the testing facilities are built to replicate various experiences. There are rows of sinks to test personal-care products, dozens of cell-like rooms to test air fresheners, washing machines that will help researchers assess the cuddliness factor of fabric softeners, clotheslines to test detergents on hang-dried clothes, and functioning latrines to sample toilet cleaners. There’s even a place mysteriously referred to as “the stench room” to test malodors.

After hundreds of test washes and thousands of deep sniffs, a scent is finally ready to be released into the wilds of the supermarket aisle. All told, the whole process, from the capture of a cinnamon twig to the aroma on your fresh-pressed whites, takes about two years and the sweat of a huge number of people.

As I leave the IFF facility, my nose feeling a little bit like it’s about to fall off, I’m awestruck by the enormous amount of energy that’s spent on making the world smell better. Maybe it’s a little unsettling to know that consumer products have such a direct pathway into our emotional zones. Should I be skeptical the next time I put on a freshly laundered shirt and remember my childhood? Should I distrust my emotions when I polish a tabletop and feel uplifted by the lemony scent? Or should I be thankful that these mundane activities are filled with little bits of manufactured—but also very real—joy? After a long day in the lab, I’m too tired to wade into the ethical complexities of every flavor and scent that surrounds me. But I do know this: The intricate way IFF combines chemistry, biology, and psychology fills our world with meaning. And Patel’s mantra to stop and smell stays with me. A few days later, when I toss some clothes in the wash, I do exactly that, reminded that even in a simple dryer sheet, there’s a remarkable story.