London streets in the early 19th century could be dangerous places. In The London Guide and Stranger’s Safeguard Against the Cheats, Swindlers, and Pickpockets that Abound within the Bills of Mortality, Forming a Picture of London as Regards Active Life, published in 1819, “a gentleman who has made the police of the metropolis an object of enquiry twenty-two years” attempted to help strangers to the city avoid falling victim to all manners of crime—including diving, otherwise known as pickpocketing. “This way of obtaining the property of others, is certainly the most genteel, profitable, and alluring of any,” the author notes, “because it requires some degree of ingenuity to exercise it properly, and a great deal of address and firmness to get off without detection. Professors of the art are admired for their dexterity, by every one but the immediate losers.” Here were some of the author’s tips that would help newcomers to the city keep their wallets—some of which we should heed even today.

1. Don’t act like a tourist.

Fitting in was the name of the game in London. Newcomers, according to the author, were

easily recognized by their provincial gait, dialect, and cut of the cloth ; by the interest they take in the commonest occurrences imaginable, and the broad stare of wonder at every thing they see. … It would be surprising indeed, if the knavish part of the community did not endeavour to profit by the want of knowledge apparent in Johnny Newcome, or Johnny Raw, as such men are aptly called. He is followed for miles, sometimes for an entire day or more, by a string of pickpockets or highwaymen, until they can find an opportunity to do him.

The solution, then, was to “appear like a thorough bred cockney in your gait and manner, by placing the hat a little awry, and with an unconcerned stare, penetrating the wily countenances of the rogues; you attain one more chance, at least, of escaping the snares that are always laid to entrap the countryman or new comer.”

2. Walk the right way.

According to the author, walking in London wasn’t a simple thing; in fact, it was a system, with “every one taking the right hand of another, whereby confusion is avoided ; thus, if you walk from St. Paul's towards the Royal Exchange, you will be entitled to the wall of those you meet all the way ; whereas, if you cross over, you must walk upon the kirb stone.”

Walking in a “contrary mode” was sure to attract the attention of pickpockets, who would “hustle such an one against his accomplice in the day time ; the stranger will be irritated no doubt, and express his indignation, which will be the better for the rogues : in a half-minute's altercation, they get the best of the jaw, because the loudest and most impudent; —a spar or two ensues, in which he who pretends to support the stranger to the ways of town, draws him of his pocket-book, or his watch, if he has either, a fact they take care to ascertain beforehand.”

To avoid this unfortunate fate, the author stresses the “necessity of cautiously, yet energetically, pursuing his way, without dread or doubt ; since it is better to walk a little out of the right path, than run the risk of being directed wrong."

3. Avoid crowds.

Hanging out in places where many people were gathered increased a person’s chances of losing his wallet—especially if there’s some kind of kerfuffle. “If a horse tumbles, or a woman faints, away [pickpockets] run to encrease the crowd, and the confusion ; they create a bustle, and try over the pockets of unsuspecting persons,” the author says. He advises "steer[ing] clear of assemblages in the streets, by going round them." If that's unavoidable, "pressing rather rudely through them" is the key: "You become the assailant, if I may be allowed the term, and add one more chance of steering clear of danger.”

4. Don’t ask for directions in the street.

Pickpockets would target “silly persons” who “stand gaping at the names of streets, as if in doubt which road to take,” and asked people on the street which way they should go. The thieves would hustle the hick to an alleyway or some other ideal area to either “neatly” pick his pockets or beat him up and take his money. The author advises “that no one should ask his way in the street, but in decent shops."

If a man couldn't find a decent shop, he was advised to ask someone carrying a small parcel; this showed that "they are shopmen or porters," the writer says, and thus could be trusted. "Thieves do not go about encumbered in that manner, at least not hitherto ; but they might possibly adopt it hereafter, from this hint.” Oops.

5. Be on the lookout for shabby clothing.

Though “thieves frequently go well-dressed, especially pickpockets,” a close observer “may always discover in the dress of the genteel pickpocket, some want of unity, or shabby article, as a rusty hat, or the boot-tops in bad order, or a dirty shirt and cravat.”

6. Men: Avoid ladies out at night...

“Women who walk the streets at night, are invariably pickpockets,” the author advises. “I see no reason to set down those who by day entice the men into their dens, any thing better. Such as stand at the corners of lanes and courts, inviting men to stop, are clumsy hands, but contrive to pick up a good harvest occasionally : they rob indiscriminately every article of dress, knocking off the silly (perhaps drunken) man's hat in the street, with which the accomplice runs away ; at other times they will take off his cravat, while bestowing upon him their salacious caresses. A broach, or shirt-pin, is constantly made good prize of, but should the deluded man enter one of pestiferous abodes, which are so numerous in this metropolis, the loss of all he has is inevitable.”

7. ... And Beware of women asking silly questions.

Just in case that first tip wasn't enough, the author really wanted to drive home the point that ladies could be pickpockets, too, so the best course of action was just to breeze by them. “It is recommended over again not to be stopped in the streets, even by a handsome woman." It was for a man's own good. Lady pickpockets possessed, according to the author,

great nimbleness of fingers, and convey away your property while talking you into a silly passion for their persons. Although it seems brutish to rebuke a woman who should press against you in a crowd, in a church, at an auction, or in the streets, yet this should be done. … Such women amuse you with asking silly questions ; perhaps complain to you of some man who is pressing her, while one of her accomplices rifles your pockets in the mean time, from behind another accomplice, who keeps his arms up so as to prevent yours from defending your property.

A woman might even grab a man's arm, "as if for protection," but what she was really doing was keeping him from using it. Goodbye, wallet!

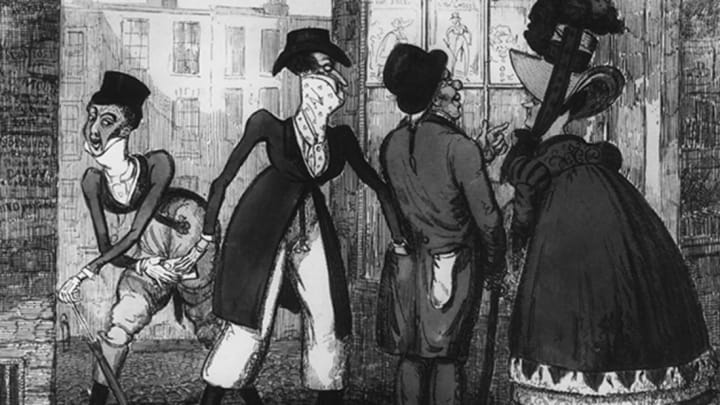

8. Ladies, don't window shop.

Or if they did, they should at least have the good sense to not get so close to the windows that a thief could get under their skirts. “Ladies who press to the windows of drapers shops are fine game,” the author says. “When they wore pockets with hoops, scarcely any operation in all the light finger trade was easier than the dive, or putting in one's hand ; afterwards, on the disuse of the hoop, the thing was performed by a short fellow, or boy, getting between the legs of the accomplice (a tall one) and spreading the petticoats, cut off the pockets, with a knife attached to the hand.”

9. And If you do get your pockets picked, don’t go after the thief.

“Should a pickpocket take to his heels, and be easily distinguished from his followers, it is not always advisable to stop him,” the author cautions. After all, “some are armed with knives, which they would not hesitate to use in a scuffle.”