December 5, 1974, was a chilly night at Legion Field in Birmingham, Alabama, site of the World Bowl. It was a slightly warmer night in Jacksonville, Florida, the scheduled site of the first championship game of the World Football League, but when the Jacksonville Sharks folded fourteen games into the season, the idea of holding the title game there seemed a little, well, like piling on.

The night was shaping up to be a classic battle between the hometown Birmingham Americans and the Florida Blazers. The Americans had the league’s second-best record during the regular season, going 15-5 during the 20 game schedule, and the Blazers arrived in Birmingham by upsetting the best team in the league, the Memphis Southmen, in the semifinals.

Truth be told, winning was the easy part of getting to the World Bowl. Three days before the Big Game, the Americans threatened to not play because they hadn’t been paid in five weeks. The owner begged them to show up on the promise that if they won, he would give them championship rings. No mention was made of back pay, however. The Blazers, meanwhile, hadn’t been paid in four months. Throughout the season, Florida coaches had been charged with not only calling plays, but also making sure bathrooms were filled with toilet paper. Every week Florida players found themselves at the local McDonald’s for their free meal of the day.

Nevertheless, despite all the financial issues, both teams made it to 72,000-seat Legion Field, less than half of which was filled for their world championship tilt.

Game on

Tri-MVP Ceremony With Delta Burke

At halftime, the Americans had a 15-0 lead and looked to be in complete command. The first touchdown was scored by Birmingham's cruelly named running back Joe Profit.

Fans were entertained at the break by the announcement of the league’s Most Valuable Player—or, in this case, players. Running back Tommy Reamon of the Blazers, running back JJ Jennings of the Memphis Southmen, and quarterback Tony Adams of the Southern California Sun were all named Tri-MVPs. Each player received a 1/3 share of the $10,000 prize given for winning the award. Because of the financial issues throughout the season, the league thought it best to give the players cash, fearing the possible public humiliation of three $3,333.33 checks bouncing.

Helping to make the presentation at halftime was Miss Florida 1974, Delta Burke. Missing was Jennings, who, despite the risk of having a check mailed to him, chose instead to have a tonsillectomy that day. Adams was there and Reamon, who was playing in the game, had to be pulled from the locker room. He came out, took his envelope, ran to the stands, and handed it to his mom before rejoining his teammates to get ready for the second half.

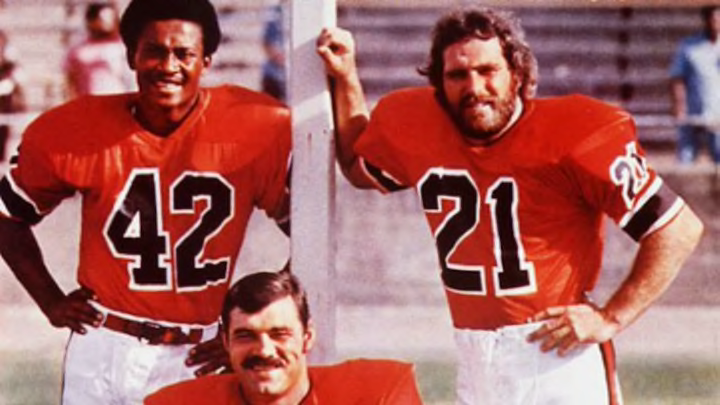

Art Cantrelle Scores in the World Bowl // Courtesy of Greg Allred (wfl1974.com)

When the clock hit double zeros, the Americans had survived a furious comeback to nip the Blazers, 22-21.

As both teams made their way off the field, Billie Hayes from Florida tried to retrieve the ball. He was gang-tackled by a group of Birmingham players, who thought the ball should be theirs. After all, they did win. A fight broke out between the teams. The ball popped out, and a ball boy named Walter Bridges picked it up and started running.

Where he was going, no one was sure, but at that point both teams decided it was more important to get the ball back than it was to fight each other. En masse, they took off after him. Needless to say, they got the kid and the ball. Birmingham tackle Paul Costa handed it—the ball, that is—to team captain Ross Brupbacher who said, “The game ball goes to the city of Birmingham…and I hope they bring us back next year to play.”

Prior to the final whistle, Americans running back Jimmy Edwards had been ejected from the game. As he made his way to the locker room, he discovered Jefferson County sheriff’s deputies were waiting to confiscate the team’s uniforms, helmets, and equipment due to an outstanding balance owed to Hibbett’s, the sporting goods store that supplied the team.

Edwards ran back on the field to warn his teammates, a few of whom took their jerseys off after the game and handed them to family members. Back in the locker room, a deputy approached team trainer Drew Ferguson and asked if his shoes had come from Hibbett’s. When he said yes, he had to hand them over. And so, after a joyous celebration, the World Football League champion Birmingham Americans went home with nothing more than a title, and their trainer went home in his socks.

Said Head Coach Jack Gotta, “I don’t know what happens tomorrow, but tonight is the greatest night of my life.”

The Right Guy at the Right Time

Gary Davidson was the right guy at the right time. He was the quintessential anti-establishment guy, and his defiant heart was filled with an indomitable '70s spirit. Before the WFL, Davidson was the co-founder and president of two professional sports leagues, the American Basketball Association in 1967 and the World Hockey Association in 1971. These weren’t just rival leagues. These were the rebels with a cause, and their cause was to change the game, both literally and figuratively. The ABA had a red-white-and-blue basketball, a three point shot, a slam-dunk contest, and Dr. J. The WHA had a blue puck (Davidson was talked out of a red one), were the first to sign European players, and brought the world the professional debut of a skinny little Canadian kid named Wayne Gretzky. When the ABA and WHA both folded after 9 and 7 years respectively, the NBA and NHL each cherry-picked four of their franchises to bring into their leagues, one of which is the five-time NBA champion San Antonio Spurs.

“Davidson was a very aggressive businessman,” says Greg Allred, a WFL aficionado. His blog, wfl1974.com, chronicles much of the story of the Americans' championship season, and his knowledge of the league runs deep. “He understood show business and marketing, and he had an innate ability to sell a product. He was a very shrewd guy.”

Tackling the NFL

Bumped SI Cover

The labor agreement between the National Football League's Players Association and the NFL was up for renewal, and at the heart of the discussions was the idea of free agency. Since the NFL formalized a merger with the American Football League in 1966, the players were at the mercy of the owners—they had no alternate league to find work. Obviously, NFL owners were okay with that. There was talk of the first-ever players strike in 1974, and considering the average salary of an NFL player at the time was a little over $30,000, it seemed logical the athletes would welcome the idea of having another option.

On October 3, 1973, Davidson announced the WFL would begin play on July 10, 1974. He had worked quickly to compile a group of owners for twelve teams across the country: the Birmingham Americans, Boston Bulls, Chicago Fire, Detroit Wheels, Florida Blazers, Honolulu Hawaiians, Houston Texans, Toronto Northmen, New York Stars, Philadelphia Bell, Southern California Sun and Washington Ambassadors. Years later, Davidson was quoted in Sports Illustrated as saying: “We made mistakes in ownership selection. We let people come into the league because of a time frame that we might have held back on if we have decided to start play in 1975 instead of 1974.”

Of the teams named at that first press conference, only three would ultimately keep their original city and ownership group. And while all new leagues have some degree of chaos and upheaval when they begin, the WFL took the chaos to the next level:

* The Orlando team was sold and quickly moved to Jacksonville. The owner, Frank Monaco, had enough money to make one payroll, so he borrowed money from his coach and then fired him.

* The Detroit franchise was nearly sold to a guy named Bob Huchul, who, as it turned out, had been arrested 30 times and faced more than 25 lawsuits from previous business ventures.

* The team in Washington couldn’t find a place to play, so they moved to nearby Baltimore. Unable to find a lease in Baltimore, they moved to Norfolk, Virginia. Still not able to make things work, the owner sold to someone who moved the team to Orlando and they became the Florida Blazers. The franchise moved four times before they ever stepped on the field.

* John Bassett Jr., a successful Canadian businessman and clearly the most financially solvent owner in the league, owned rights to the Toronto Northmen. Subsequently, the Canadian government stepped in and introduced legislation to ban any professional football in the country other than the Canadian Football League. Bassett promptly packed up and moved his team to Memphis, changing his Northmen to, more accurately, the Southmen. (As an aside, between 1993 and 1994, the Canadian Football League, apparently not so protective of their league and their country anymore, admitted six American teams.)

As the July kickoff approached, ownership was (somewhat) in place. Now, the league actually needed players.

They held the first round of their college draft in January and the first pick was quarterback David Jaynes of the University of Kansas.

Appreciative of the honor, Jaynes said thanks but no thanks and wound up having a short and uneventful career with the Kansas City Chiefs. They also held a pro draft and the first pick was running back Charlie Evans of the New York Giants. He also said no. Ultimately, most rosters were comprised of college kids, CFL players, some minor leaguers, and more than 300 NFL players who opted to jump.

In February, Davidson announced the league had signed a TV contract with independent network TVS to broadcast a national game of the week on Thursday nights.

In March, Memphis owner Bassett made headlines on every sports page in the country when he signed three of the biggest stars from the World Champion Miami Dolphins—Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick, and Paul Warfield—to an estimated $3 million contract to play for the Southmen in 1975.

When Calvin Hill of the Cowboys and Ted Kwalick of the 49ers signed to play for the Honolulu Hawaiians in 1975, Sports Illustrated jumped on the bandwagon and was prepared to run an April 15, 1974 cover featuring the two players and Davidson under the headline: “Pro Football Goes to War.”

Unfortunately, while pro football went to war, Hank Aaron went to bat. When he hit his record-breaking 715th home run that week, the WFL cover didn’t make the newsstands.

Some might have called this a sign.

New League, New Game

Courtesy of Greg Allred (wfl1974.com)

Just like the ABA and WHA, Davidson and his new league weren’t going to follow the old rules. He promised an exciting, energetic brand of football, playing directly off the growing criticism that the NFL was boring.

Along with their twenty game regular season, a gold football with orange stripes, hip, modern uniforms, and the world’s largest collection of sports teams that didn’t end in the letter “S” (Bell, Fire, Southmen, Storm, Sun, Steamer), the league instituted eleven unique rules including:

* Moving the kickoff from the 40 to the 30 to improve run backs

* Moving the goalposts from the front of the end zone to the back line

* A fifteen minute overtime period to decide ties (more like soccer than sudden death)

Because there was a belief that the NFL was becoming a field goal kicker dominated league, the WFL instituted other rule changes to lessen the importance of kickers. Those included:

* Missed field goals would be returned to the spot of the miss

* No extra points. Touchdowns would be worth 7 not 6, and everyone had the opportunity to get an “Action Point” where you could run or pass your way to an extra point from the two yard line.

NFL owners and Commissioner Pete Rozelle, fearful WFL games might be more wide open and exciting than theirs, quickly adopted versions of many of these rules changes. And forty years later, the WFL seems prescient, as the NFL is now considering eliminating the extra point as well. Even Keith Olbermann recently gave the WFL some praise.

Season one for the WFL kicked off on July 10, 1974. It was a great debut.

Five opening night games totaled nearly 200,000 fans. The Philadelphia Bell outdrew the Phillies by more than 20,000. Even Elvis showed up in Memphis to watch the Southmen’s opening game.

The league was getting positive press. Life was good. And it didn’t hurt that the NFL was on strike.

The WFL had—at least for a short while—become the NFL. It was the only game in town.

Then August arrived and things started to spiral. There were revelations that attendance numbers were, to put it mildly, inflated. Of the 120,000 fans at the first two Philadelphia Bell games, more than 100,000 got in either free or for a significantly reduced price. Jacksonville was doing the same thing. Rumors started circulating that teams across the league were struggling to meet payroll. The Southern California Sun, one of the more stable teams in the league, were running away with the Western Division when their owner, Larry Hatfield, was indicted by a federal grand jury for making false statements to obtain loans—one of which was the loan for the Sun.

The Detroit Wheels ran out of adhesive tape and had to borrow it from other teams. Management of the Portland Storm appealed to the team’s booster club to help feed the players before games. At one point, Birmingham flew to Portland for a game, and when they got on the bus to take them to the hotel, the bus didn’t move. After several minutes of awkward silence, the bus driver said he needed to be paid in advance because the last time he drove a WFL team somewhere he had been stiffed. The players dug into their pockets and pooled enough money to get the bus moving.

There was also this strange event in Houston: Defensive end John Matuszak suddenly bolted the NFL Houston Oilers for the WFL Houston Texans. This was a huge coup for the league, as Matuszak was one of the biggest defensive names in the NFL. Exactly seven plays into his new job with the Texans, he was handed a restraining order on the sidelines, forbidding him from playing.

He waved the paperwork to the crowd and spent the rest of the game on the bench. The courts later ordered he couldn’t join the WFL until his NFL contract ended after the 1977 season.

Halfway through the season, the Houston Texans moved to become the Shreveport Steamers and the New York Stars moved to become the Charlotte Hornets. In early October, the WFL suspended the Detroit and Jacksonville franchises because of financial issues. Three days later, it turned out “suspension” was secret code for “You guys don’t have a team anymore.”

That first year, the league lost nearly $20,000,000 and put Gary Davidson into bankruptcy. After an internal power struggle, he walked away and never was involved in sports again. The league named Chris Hemmeter, owner of the Honolulu Hawaiians, as commissioner. Hemmeter made it clear there would be some changes, and that there would be a second season.

The question was, did anyone care?

A few days after the World Bowl, shaken, battered, and determined league officials met in New York City to concoct a survival strategy. Commissioner Hemmeter announced the “Hemmeter Plan,” a profit-sharing plan to ensure that players would be paid in 1975. It stipulated that the players would receive a percentage of the owners’ profits, and if there were no profits, the players would receive $500 a game.

The league came back in season two with eleven teams, some new, some moved, and some completely re-formed. Some teams were still looking for coaches when the season started. In July, the Philadelphia Bell named former Green Bay Packers safety Willie Wood their head coach, making him the first African American head coach in pro football history.

The new ownership group in Chicago tried to make a splash by offering a $5 million contract to Joe Namath. CBS allegedly said that if Namath signed with the WFL, they would be willing to talk TV contract. Simultaneously, Namath was offered a $5 million contract to be a spokesman for Faberge. It wasn’t too difficult a decision for Namath, who stayed with the Jets, got a big payday from Faberge and was forced to work in unbearable conditions like this:

The CBS contract rumor disappeared and the league found itself with no national TV carrier. Any TV broadcasts for the 1975 season would be local. This would prove another huge financial burden.

Nevertheless, they pushed on. Even without Davidson, the WFL continued to bring out-of-the-box ideas to the table. The league announced they would be testing a uniform change for every team during the preseason. The official press release explained:

All offensive linemen will wear purple pants, running backs green pants and receivers orange pants, while defensive lineman will be dressed in blue, linebackers in red and defensive backs in yellow. The various colors are emphasized by vertical striping. Quarterbacks and kickers will wear white. The various colored pants are the idea of William B. Finneran, a New York management consultant who also invented the Action Point. Finneran refers to the pants idea as “color dynamics” which he defines as “the concept of implementing means whereby one’s visual appreciation of dynamic movement is significantly increased.” "Most importantly," says Finneran, “color coding is for the benefit and enjoyment of the fans. It has no significant impact on the game itself." The concept will insure easier comprehension of the game and for those sometime fans, such as women. In a sense the color grids will serve as the TV "color commentator" for the crowd at the stadium since they will help explain the action. They will also of course improve viewing on color television.

Says JJ Jennings, “The league had a lot of good ideas. That wasn’t one of them.” The pants were shelved before the season started.

Those Pants // Courtesy of Richie Franklin (charlottlehornetswfl.com)

On the bright side, the WFL finally got its Sports Illustrated cover in 1975, featuring Csonka, Kiick and Warfield preparing for the season in Memphis.

This was a much “cleaner” cover than the last time Csonka and Kiick were on the cover of SI together—in 1972 when Csonka gave the one-finger salute and nobody noticed until it was too late.

Year two of the WFL kicked off at the end of July 1975 with eleven teams. By week three, that number was down to ten, as the Chicago Winds folded. By early October, with continued financial strife and poor attendance, the league held an emergency meeting and Hemmeter defiantly declared the league would survive. It did...for nine more days. On October 22, he announced the league was disbanding. In his closing remarks, Hemmeter cited the reasons for failure were bad weather, competition with the NFL, media skepticism, and the availability of star players.

Thirty two games in, the WFL was officially dead

Even today, former players agree that if you stripped away all the financial issues, the football itself was great. “We could hold our own with anybody,” says Reamon. Now a high school coach in Newport News, Virginia (he coached Michael Vick and current Steelers Head Coach Mike Tomlin among others), Reamon says, “I was the youngest guy on our team. We had a lot of older NFL guys and they all said the quality of the game we played was second to none.”

During the ’74 season, Reamon had made the unwise decision of having his salary deferred to the end of the year, meaning he had earned a total of $1,500 (his bonus) for the entire season, plus the $3,333.33 for sharing the MVP award. “Honestly, I have no regrets,” he says. “For me, the WFL made sense in a lot of ways. The NFL was on strike and it was a chance to show them they made a mistake by not picking me in the first round. The WFL gave me an opportunity to showcase my talents.”

After the 1974 season, Reamon’s coach in Florida, Jack Pardee, jumped ship and took the head coaching job with the Chicago Bears in the NFL. The Bears tried to work a trade to get Reamon’s rights from the Pittsburgh Steelers, but they couldn’t agree on a deal. Instead, the Bears drafted a running back named Walter Payton. Reamon was later traded to the newly-formed Jacksonville Express in '75. He played for the Chiefs in the NFL in 1976, Saskatchewan in the CFL in ’77, and retired from professional football in ’78. “No regrets,” he says. “I wouldn’t change a thing.”

Despite being one of the Tri-MVPs, JJ Jennings was also traded in ’75 to Philadelphia when Csonka, Kiick, and Warfield showed up in Memphis. “There wasn’t any room for me or my hair,” he says. He agrees with Reamon that the play on the field was more than solid. “Our team was a bit of an outlier in the league,” he says. “We had a great owner [Bassett]. Getting paid was never an issue, and we were a quality organization through and through. I have no regrets. We kept a lot of people working for a couple of years and the football was good. Really good.”

Richie Franklin was a 13 year old when the WFL hit his TV. Since then, he’s dedicated countless hours, energy, and emotion to keeping the spirit of the WFL alive. “I was an impressionable young kid,” he says. “I thought the ball and the uniforms were so great. I had never seen anything like this before. It’s forty years later and no one can ever take those memories away.” His site, wfl.charlottehornets.com, is the definitive source of information on the league’s history, including interviews with players and details long since forgotten by most. “It’s been a labor of love,” he says. “I just want to keep the spirit alive.”

Looking back, a league that was seemingly a blip on the football radar had a remarkable impact. The WFL created rule changes which still exist today, helped open the door for NFL free agency, created coaching opportunities for men like Jack Pardee, Marty Schottenheimer, Jim Fassel, and Lindy Infante, and launched the NFL careers of Danny White, Alfred Jenkins, Pat Haden, and more.

“Ultimately, the death of the WFL was unstable ownership and lack of a TV contract,” says Allred. “But in terms of football the way we know it today, the WFL was a very forward thinking league.”

As it turns out, too forward, too soon.