A big, hairy spider is enough to give anyone a fright. So you can imagine what a set of eight glowing eyes attached to a body like that might do to an arachnophobe's psyche. One such spider was discovered recently by researchers, but don’t worry—the iridescent-eyed arachnid has been dead for 110 million years.

As Popular Science reports, this rare, fossilized specimen was found in South Korea’s Lower Cretaceous Jinju Formation. The find was unusual for a couple of reasons. For one, spiders are not usually preserved in rock because the soft-bodied creatures decay easily. It’s also not every day that you see a long-dead spider with glowing eyes. On top of that, researchers found two well-preserved examples of these spiders, which were described in a recent issue of the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

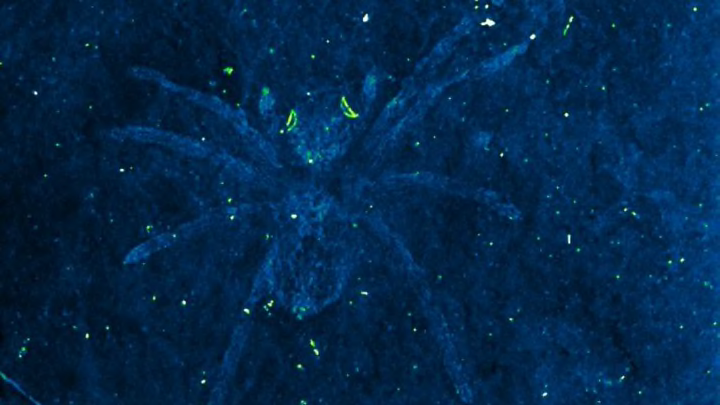

Both specimens belong to Lagonomegopidae, an extinct family that predated jumping spiders. The glow is caused by a layer of tissue called tapetum lucidum, which coats the spider’s eyes and reflects light, allowing the spider to hunt at night with ease. Many animals have it—including cats, dogs, horses, deer, raccoons, and some modern spiders—but this is the first paper to describe its existence in a fossilized spider. The tapetum is crescent-shaped and “looks a bit like a Canadian canoe,” according to Paul Selden, a geology professor at the University of Kansas and co-author of the paper.

“Because these spiders were preserved in strange silvery flecks on dark rock, what was immediately obvious was their rather large eyes brightly marked with crescentic features,” Selden said in a statement.

Researchers now want to go back and take another look at similar spiders preserved in amber, which are far more common than spiders fossilized in rock. The challenge is determining whether those specimens also have a layer of tapetum lucidum coating their eyes.

“Amber fossils are beautiful, they look wonderful, but they preserve things in a different way,” Selden said. “Now, we want to go back and look at the amber fossils and see if we can find the tapetum, which stares out at you from rock fossils but isn’t so obvious in amber ones because the mode of preservation is so different.”

[h/t Popular Science]