The Arabic and Simplified Chinese scripts aren't in danger of going anywhere anytime soon, but the same can't be said for Balinese, Mali, Pahawh (or Pahauh) Hmong, and the other 100-some alphabets that Vermont-based writer Tim Brookes has cataloged in his online Atlas of Endangered Alphabets, which is set for a soft launch on January 17. The featured alphabets—which Brookes has loosely defined to include writing systems of all sorts—are vanishing for varied reasons, including government policies, war, persecution, cultural assimilation, and globalization.

“The world is becoming much more dependent on global communications and those global communications take place in a relatively small number of writing systems—really something between 15 and 20,” Brookes tells Mental Floss. “And because that’s the case, all the others are to some degree being eroded.”

The atlas will include a bit of background information about each alphabet as well as links to any organizations attempting to revive them. By creating a hub for these alphabets, Brookes hopes to connect people who want to preserve their language and culture, while also showing the world how beautiful and intricate some of these scripts—including the 10 below—can be.

1. Cherokee

Although the Manataka American Indian Council says an ancient Cherokee writing system may have existed at one point but was lost to history, Cherokee was more or less a spoken language up until the early 19th century. Around 1809, a Cherokee man named Sequoyah started working on an 86-character writing system known as a syllabary, in which the symbols represent syllables. Most remarkably, Sequoyah himself had never learned how to read. At the time, many Native Americans deeply distrusted writing systems, and Sequoyah was put on trial for witchcraft after tribal leaders caught wind of his new creation. However, once they realized that written Cherokee could be used to preserve their language and culture, they asked Sequoyah to start teaching the syllabary. “The Cherokee achieved 90 percent literacy more rapidly than any other people in history that we know of,” Brookes says. “[Sequoyah’s syllabary] is one of the greatest intellectual achievements of all time.”

After a period of decline in the years following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Cherokee language education saw somewhat of a revival in the late 20th century. The predominance of English and the Latin alphabet has made these efforts an uphill battle, though. Brookes says it’s difficult to find people who can teach the script, and even among Cherokee translators, few are confident in their grasp of the writing system.

2. Inuktitut

Nine different writing systems are used among Canada’s 59,500 Inuit. Many of these are based on the Latin alphabet, but the one shown above uses syllabics that were first introduced by European missionaries in the 19th century. Since it’s difficult and costly to represent each of these writing systems in official documents, many Inuit officials write and hold meetings in English, all but ensuring the demise of their mother tongue. However, Canada’s national Inuit organization, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, is now in the process of developing one common script for all Inuit. “Our current writing systems were introduced through the process of colonization,” the organization writes on its website. “The unified Inuktut [the collective name for Inuit languages] writing system will be the first writing system created by Inuit for Inuit in Canada.” It remains to be seen what that script will look like.

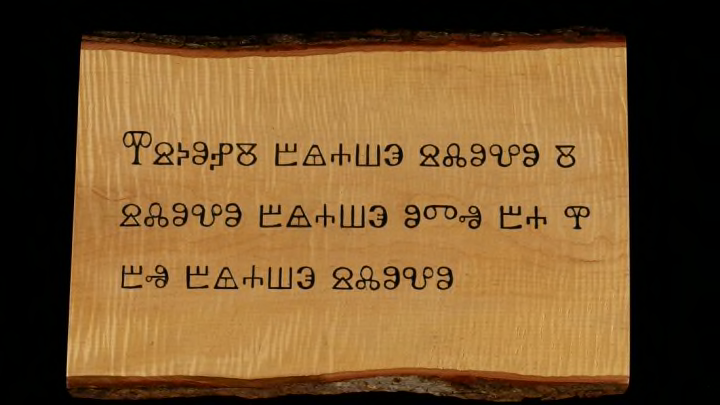

3. Glagolitic

It’s widely believed that Glagolitic, the oldest known Slavic script, was invented by missionaries Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius around 860 CE in an effort to translate the Gospels and convert the Slavs to Christianity. The name Glagolitic stems from the Old Church Slavonic word glagolati, meaning to speak. Some of the symbols were lifted from Greek, Armenian, and Georgian, while others were entirely new inventions. Nowadays, academics are typically the only ones who can decipher the script, but some cultural institutions have made efforts to preserve its legacy. In 2018, the National and University Library in Zagreb launched an online portal containing digitized versions of Glagolitic texts. In addition to being a source of Croatian heritage and pride, the alphabet has also become an object of tourist fascination. Visitors can view monuments containing Glagolitic symbols along the Baška Glagolitic Path on the Croatian island of Krk. And in Zagreb, the capital city, it’s not hard to find gift shops selling merchandise adorned with Glagolitic writing. However helpful this may be to the tourism sector, it's no guarantee that more Croatians will want to start learning the script.

4. Mandombe

This African script is unusual for several reasons. For one, the Mandombe alphabet reportedly came to David Wabeladio Payi—a member of the Kimbanguist church in the Democratic Republic of Congo—in a series of dreams and spiritual encounters in the late ‘70s. One day, he was looking at his wall when he noticed that the mortar between the bricks seemed to form two numbers: five and two. He believed these were divine clues, so he set out to create a series of symbols based off those shapes. Eventually, he assigned the symbols phonographic meaning and turned it into an alphabet that could be used by speakers of the Kikongo and Lingala languages. Perhaps most remarkably, the pronunciation changes depending on how the symbols are rotated. “It’s one of about three writing systems in the world where that’s true,” Brookes says. Unlike most of the other alphabets on this list, Mandombe is growing in popularity rather than declining. However, because it’s primarily being taught in Kimbanguist schools and used only for religious texts, it will be a challenge to convince the rest of the population to start using it. Elsewhere in the country, the Latin alphabet is used (French is the official language). “What it’s up against is, in essence, exactly the same forces that a declining script is up against,” Brookes says. For this reason, many new alphabets can be considered endangered.

5. Ditema tsa Dinoko

In a similar vein, Ditema tsa Dinoko is also a minority script, and it's too new to tell if it will stick around. A team of South African linguists, designers, and software programmers invented this intricate, triangular-shaped alphabet in just the last decade in hopes of forging a single script that could be used by speakers of indigenous languages in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. Because the symbols were inspired by artworks and beadwork designs that are typical of the region, the alphabet is also a celebration of culture. “One of the really interesting features of African alphabets is how deeply embedded they are in what we would call graphic design,” Brookes says. “Instead of imitating the shapes or structures or layout of other writing systems, such as our alphabet, they often start from a completely different point of view and draw on designs that are found in war paintings, weaving textiles, pottery, and all of those other available graphic elements.” The colors used in the alphabet aren't necessary to understand the script, but they hark back to the alphabet's artistic origins while also functioning as a kind of font. For instance, different writers may use different colors to give their text "a certain feel or emotional resonance," Brookes says.

6. Mandaic

This ancient, mystic script dates back to the 2nd century CE and is still being used by some Mandaeans in Iraq and Iran. According to mythology, the language itself predates humanity, and the script was historically used to create religious texts. Charles Häberl, now an associate professor of Middle Eastern languages and literatures at Rutgers University, wrote in a 2006 paper that Mandaic is “unlike any other script found in the modern Middle East." And unlike most scripts, it has changed very little over the centuries. Despite its enduring quality, many of the speakers in Iraq have fled to other countries since the U.S. invasion in 2003. As these speakers assimilate into new cultures, it becomes more challenging to maintain their linguistic traditions.

7. Lanna

According to Brookes, the Lanna script was primarily used during the time of the Lanna Kingdom in present-day Thailand from the 13th century to the 16th century. It’s still used in some regions of northern Thailand, but faces stiff competition from the predominant Thai script. The word Lanna translates to "land of a million rice fields." The script is one of Brookes’s personal favorites as far aesthetics are concerned. “It is so extraordinarily fluid and beautiful,” he says. “They developed this script to indicate not only consonants, but then the consonants have vowel markings and other consonant markings and tonal markings both above and below the main letters, and so you have this amazingly joyous and elaborate writing system, and it’s like a pond of goldfish. Everything is just curving around and swimming in all these different directions.”

8. Dongba

Members of the Naxi ethnic minority in China’s Yunnan province have been using this colorful pictographic script for well over 1000 years. The pictures stand for tangible objects like mud, mountains, and high alpine meadows, as well as intangible concepts such as humanity and religion [PDF]. Historically, it was mainly used by priests to help them remember their ceremonial rites, and the word Dongba means "wise man." However, the script has undergone something of a revival in recent years, having been promoted by people working in the arts and tourism industries. It’s also taught in some elementary schools, and it remains one of the few pictographic scripts that’s still in use today. At the same time, Brookes says he's seen little evidence of efforts "to create a circumstance where the script is actually used in a functional, everyday fashion." With the predominant Chinese script looming large throughout much of the country, Dongba's days may be numbered.

9. Tibetan

Some of the world’s alphabets and languages are endangered for political reasons. Tibetan is perhaps the best-known example of that. The Chinese government has cracked down on language instruction in recent years, with the aim of promoting Mandarin, the predominant language—although some have argued this policy comes at the expense of minority languages. In Tibet, many schools now conduct the bulk of their lessons in Mandarin, and Tibetan might be taught in a separate language course. Chinese officials put a Tibetan activist on trial in January 2018 for “inciting separatism”—partly because he criticized the government’s policies on Tibetan language education. He was sentenced to five years in prison. In general, “the story behind endangered alphabets is almost never a pleasant or cheerful one, so that’s the human rights side of it,” Brookes says.

10. Mongolian

Some have likened the appearance of the traditional Mongolian script to a kind of vertical Arabic. The script traveled to Mongolia by way of a Turkic ethnic group called the Uighurs in the 1100s. Beginning with Genghis Khan, Mongol leaders used the script to record historic events during their reign. Later, when Mongolia became a Soviet satellite state, the country started using the Cyrillic alphabet in the 1940s, and the traditional script was largely cast aside. The traditional alphabet is still used in inner Mongolia and is returning to Mongolia, and the renaissance of Mongolian calligraphy has bolstered its usage to some degree. Nonetheless, it, too, remains endangered.