As a city that's been around for almost 2000 years, London has seen its fair share of violence. Some of those centuries-old murders are still infamous today—Jack the Ripper's, for instance—but many more run-of-the-mill crimes have been long forgotten. A new mapping project from the Violence Research Center at the University of Cambridge's Institute of Criminology, spotted by the BBC, explores almost 150 of these long-forgotten murders.

The Interactive London Medieval Murder Map (which you can view in its full form here) tracks 142 homicide cases recorded in late medieval London from 1300 to 1350, detailing stabbings, assaults, infanticides, and other deadly encounters. They run from routine burglary-gone-wrong situations and street fights between strangers to premeditated (what we would now label first-degree murder) revenge killings and gambling quarrels.

The exhaustive graphic can be sorted by location, year, the gender of the victim, the type of weapon used, and whether the crime scene was in a public or private place. Click on the pins and you can read the details of each case, including the name of the victim, the year, and the story of the crime according to reports from the time. Each is named with a matter-of-fact summary of the crime that reads like a police blotter from centuries past: "carpenter's apprentice axes midnight burglar;" "man stabbed after altercation over tunic;" "boy stabs brewer after theft of women's clothing;" "a deadly fight between members of the fishmonger and the skinner guilds."

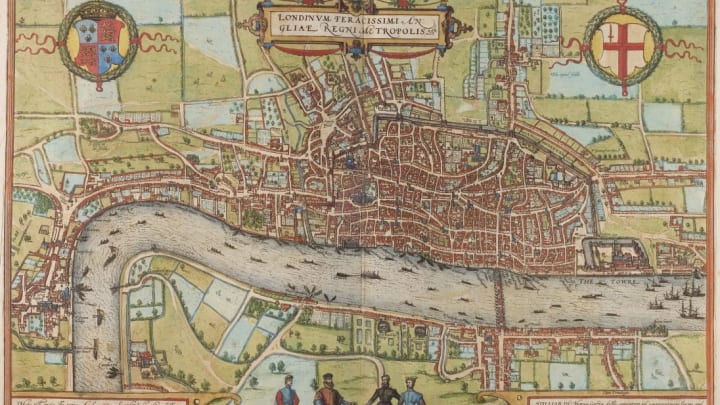

You can either view the homicide data overlaid on the Braun and Hogenberg map of London, first published in 1572, or on a map of the city circa 1270 that published by the Historic Towns Trust in 1989. The latter provides a bit better context (and a slightly easier reading experience) in terms of where the churches, streets, and landmarks mentioned in the inquests were.

The locations of the pins on the map represent where the attack occurred, rather than where the victim may have actually expired. Some are rough estimations based on the recorded notes, while others took place in locations that are easy to pinpoint now. For instance, if a specific churchyard was mentioned, the researchers could easily figure out where that would have been on the map, while other reports that mention specific businesses were harder to track down, such as the 1339 murder of Ralph Sarasyn of Twycors, who died "near the gate of the hostel of Sir William Trussel"—a hostel that researchers were unable to pinpoint the exact location of.

To learn more, the full lecture by Manuel Eisner from the project's launch is below.

[h/t BBC]