In The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth: And Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine, medical historian Thomas Morris presents a collection of bizarre but fascinating stories culled from the pages of old medical journals and other accounts. In this tale, he discusses the final moments of an aristocratic older women, Countess Cornelia di Bandi, whose demise would provide fodder for Charles Dickens over 100 years later.

Do human beings ever burst into flames? Two hundred years ago, many people believed that they could, especially if the victim was female, elderly, and a heavy drinker. Spontaneous human combustion became a fashionable topic in the early 19th century, after a number of sensational presumed cases were reported in the popular press. At a period when candles were ubiquitous and clothes often highly flammable, most were probably simple domestic fires in which the unfortunate victim’s subcutaneous fat acted as supplementary fuel. Nevertheless, the circumstances in which some were discovered—with the body almost totally incinerated, but nearby objects left untouched—led some to believe that these conflagrations must have another, more mysterious, cause. Numerous theories were put forward to explain the phenomenon: some supernatural, others scientific.

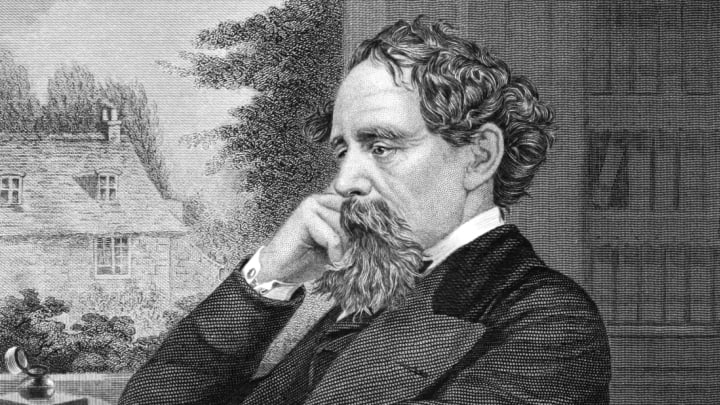

One of the true believers in spontaneous combustion was Charles Dickens, who even killed off Krook, the alcoholic rag dealer in Bleak House, by means of a fire that left nothing of the old man except an object looking like a “small charred and broken log of wood.” Dickens had read everything he could find on the subject and was convinced that its veracity had been proved. His description of the demise of Krook was based closely on that of an Italian aristocrat, Countess Cornelia di Bandi, who was consumed by a fireball in her bedroom. Her case was reported in 1731 by a clergyman called Giuseppe Bianchini, and subsequently translated by a famous Italian poet and Fellow of the Royal Society, Paolo Rolli:

"The Countess Cornelia Bandi, in the 62nd year of her age, was all day as well as she used to be; but at night was observed, when at supper, dull and heavy. She retired, was put to bed, where she passed three hours and more in familiar discourses with her maid, and in some prayers; at last falling asleep, the door was shut."

The following morning, the maid noticed that her employer had not appeared at the usual time and tried to rouse her by calling through the door. Not receiving any answer, she went outside and opened a window, through which she saw this scene of horror:

"Four feet distant from the bed there was a heap of ashes, two legs untouched from the foot to the knee with their stockings on; between them was the lady’s head; whose brains, half of the back part of the skull, and the whole chin, were burnt to ashes; amongst which were found three fingers blackened. All the rest was ashes, which had this particular quality, that they left in the hand, when taken up, a greasy and stinking moisture."

Mysteriously, the furniture and linen were virtually untouched by the conflagration.

"The bed received no damage; the blankets and sheets were only raised on one side, as when a person rises up from it, or goes in; the whole furniture, as well as the bed, was spread over with moist and ash-coloured soot, which had penetrated the chest of drawers, even to foul the linen."

The soot had even coated the surfaces of a neighboring kitchen. A piece of bread covered in the foul substance was given to several dogs, all of which refused to eat it. Given that it probably consisted of the carbonized body fat of their owner, their reluctance to indulge is understandable.

"In the room above it was, moreover, taken notice that from the lower part of the windows trickled down a greasy, loathsome, yellowish liquor; and thereabout they smelt a stink, without knowing of what; and saw the soot fly around."

The floor was also covered in a “gluish moisture,” which could not be removed. Naturally, strenuous efforts were made to establish what had caused the blaze, and several of Italy’s best minds were put to the problem. Monsignor Bianchini (described as “Prebendary of Verona”) was convinced that the fire had not been started by the obvious culprits:

"Such an effect was not produced by the light of the oil lamp, or of any candles, because common fire, even in a pile, does not consume a body to such a degree; and would have besides spread it-self to the goods of the chamber, more combustible than a human body."

Bianchini also considered the possibility that the blaze might have been caused by a thunderbolt but noted that the characteristic signs of such an event, such as scorch marks on the walls and an acrid smell, were absent. What, then, did cause the inferno? The priest came to the conclusion that ignition had actually occurred inside the woman’s body:

"The fire was caused in the entrails of the body by inflamed effluvia of her blood, by juices and fermentations in the stomach, by the many combustible matters which are abundant in living bodies, for the uses of life; and finally by the fiery evaporations which exhale from the settlings of spirit of wine, brandies, and other hot liquors in the tunica villosa [inner lining] of the stomach, and other adipose or fat membranes."

Bianchini claims that such “fiery evaporations” become more flammable at night, when the body is at rest and the breathing becomes more regular. He also points out that “sparkles” are sometimes visible when certain types of cloth are rubbed against the hair (an effect caused by discharges of static electricity) and suggests that something similar might have ignited the “combustible matters” inside her abdomen.

"What wonder is there in the case of our old lady? Her dullness before going to bed was an effect of too much heat concentrated in her breast, which hindered the perspiration through the pores of her body; which is calculated to about 40 ounces per night. Her ashes, found at four feet distance from her bed, are a plain argument that she, by natural instinct, rose up to cool her heat, and perhaps was going to open a window."

Then, however, he lets slip what is probably the genuine cause of the fire:

"The old lady was used, when she felt herself indisposed, to bathe all her body with camphorated spirit of wine; and she did it perhaps that very night."

Camphorated spirits (a solution of camphor in alcohol) was often used to treat skin complaints, and as a tonic lotion. The fact that it is also highly flammable is, apparently, quite beside the point.

"This is not a circumstance of any moment; for the best opinion is that of the internal heat and fire; which, by having been kindled in the entrails, naturally tended upwards; finding the way easier, and the matter more unctuous and combustible, left the legs untouched. The thighs were too near the origin of the fire, and therefore were also burnt by it; which was certainly increased by the urine and excrements, a very combustible matter, as one may see by its phosphorus."

So it was the “internal heat and fire” that caused the countess’s demise. Only an incorrigible skeptic would point out that an old lady who was in the habit of bathing in inflammable liquids, before going to bed in a room lit by naked flames, was a walking fire hazard.

Excerpted from The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth: And Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris. Copyright © 2018 by Thomas Morris. Published by arrangement with DUTTON, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.