“I have legs,” Nick says.

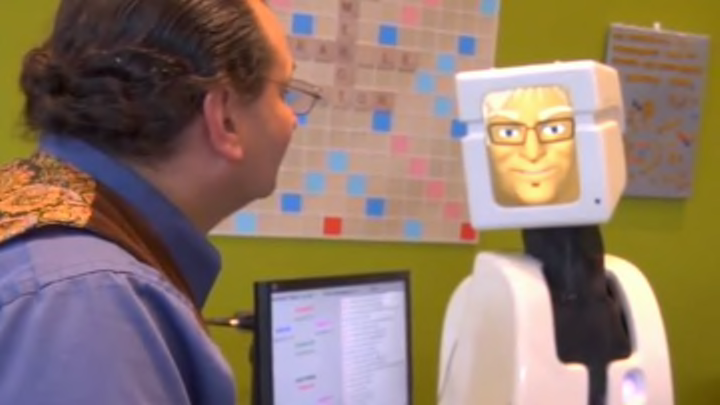

“My head alone is twice your worth,” Victor replies. Victor likes to trash talk when he plays Scrabble. My friend Nick does, too. Only Victor is a robot. A trash-talking, Scrabble-playing robot.

Victor will play Scrabble with anyone who visits the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Reid Simmons, a research professor at CMU’s Robotic Institute, came up with the idea for the gamebot five years ago. The goal is to come up with a robot that converses with humans naturally; Victor's creators hope the gamebot will help them do that. “We’re looking at how people interact and how changes in the way that Victor interacts change the way that people interact," Simmons says. "Does emotion [or] a move play a role in how people interact? Will they notice if Victor is happy or angry and will that affect the way that people interact?”

Playing Scrabble with a Robot

I am not a good Scrabble player. When the robot’s handler, Greg Armstrong, senior research technician at Carnegie Mellon University, directs me to taunt Victor by saying “I’m going to win,” the robot replies with “What scores are you looking at?” If he can’t think of a good response, the robot says, “Talk is cheap, silence is expensive.” Most of the robot's witty remarks were written by Michael Chemers, an associate professor of theater arts at the University of California, Santa Cruz. (Chemers also created the backstory for the robot and updates his Facebook page.)

Aside from the biting remarks—which increase in frequency when he is losing—Victor has an encyclopedic memory for the rules and immediately knows whether a word is valid or not. When Nick accidentally plays an incorrect word, Qa, Victor forces Nick to lose his turn—it's a Scrabble rule. But the bot has a bit of a pop culture blind spot: When Nick pulls ahead in the game and tells Victor that “resistance is futile,” the Scrabble-playing robot doesn't understand the Borg reference. Somebody forgot to program Victor with important Star Trek trivia.

When Victor becomes excited, his blockhead swivels and bobs a little, what Armstrong calls a “happy head bounce.” He has no arms or legs, so his head is the primary way he conducts nonverbal communication.

Simmons believes that by understanding how people interact with Victor, researchers will make robots that will better relate to humans. He thinks that robots will one day live with elderly or disabled people and help them live independently. Maybe a patient should be exercising, but isn’t listening to the robot’s instruction; should the robot get angry about it, or issue gentle rebukes? Using a game helps Simmons understand how people respond to robot "emotions."

“I want to emphasize we’re not doing this just to have a robot to play Scrabble," he says. "Scrabble is just the medium to have people come and sit down and interact with a robot for a longer period of time."

One disadvantage is that Victor can’t hear. At the start of the game, Victor tells us that he is deaf. We must type everything to him. This means Victor misses the casual conversation between Nick and me, making our comments to him seem forced (also, he doesn’t know that I told Nick that the humans have to work together against the robots). Simmons says he’s aware of this problem, but found that speech recognition capabilities aren’t advanced enough for Victor to hear.

“The speech recognition goes down a lot and it becomes a frustrating experience,” he says.

Simmons is keeping logs of the conversations between Scrabble players and Victor to understand how players react to Victor. After working out the kinks with the game, he plans on setting up scientific experiments to see how people act if Victor plays angry all the time or acts happy when he should act frustrated.

“[We want to] see if people notice a difference … if he plays angry when he is ahead and happy when it is behind," Simmons says. "It is very easy to change that and see how it affects how people play.”

In the end, Victor and I both lose to Nick—but we're both within 10 points of him. Until next time, Victor!