Most contractions in English are pretty straightforward: they are becomes they’re; he would is shortened to he’d; is not is isn’t; and we will is squeezed into we’ll. The two words join together, minus a few sounds. Put it together, and shorten it up. What could be easier? But that isn’t the case for will not, which becomes won’t instead of willn’t.

Why does the will change to wo? It doesn’t really. Which is to say, we didn’t change it, our linguistic ancestors did. We just inherited it from them as a unit. But there was a reason for the wo in the beginning.

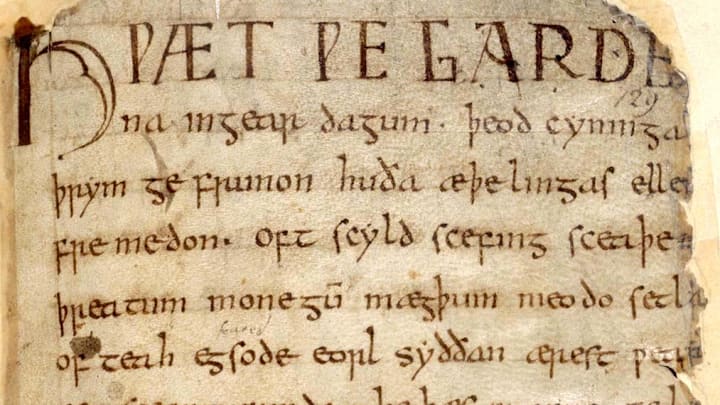

In Old English there were two forms of the verb willan (“to wish” or “to will”)—wil- in the present and wold- in the past. Over the next few centuries there was a good deal of bouncing back and forth between those vowels (and others) in all forms of the word. At different times and places , will came out as wulle, wole, wool, welle, wel, wile, wyll, and even ull and ool.

There was less variation in the contracted form. From at least the 16th century, the preferred form was wonnot, from woll not, with occasional departures later to winnot, wunnot, or the expected willn’t. In the ever-changing landscape that is English, will won the battle of the woles/wulles/ools, but for the negative contraction, wonnot simply won out, and contracted further to the won’t we use today.

When you think about the effort it takes to actually pronounce the word willn’t, this isn’t so surprising at all.

A version of this story was published in 2014; it has been updated for 2023.