Three screams pierced the night air—loud enough to be heard over the waves crashing on the rocky beach below—and Olive Dimick froze.

It was February 4, 1929, and she had just said goodnight to her next-door-neighbor Kate Jackson, after spending a night out at the movies with her. The two women lived in a cluster of cliffside bungalows overlooking Limeslade Bay in Wales, on a headland known as Mumbles. The area is said to derive its name from two shapely rock formations just offshore; according to town lore, they once looked to French sailors like les mamelles, or a pair of breasts rising from the water.

It took just a few seconds for Olive to realize the screams sounded like her neighbor, and that they were coming from the direction of her backyard. She rushed over, where she found her friend crouched on her hands and knees, bleeding from her head and moaning. Kate's husband, a fishmonger named Thomas, stood over her, half-dressed.

The pair carried Kate into the kitchen, where Olive attended to her. At about 11:45, Thomas called a doctor, who arrived around midnight and said that Kate should be taken to the hospital. Once there—Thomas, Kate, and Olive travelled in a taxi, the doctor in his own car—Thomas made a very curious remark. When the doctor asked through the taxicab window how Kate was doing, Thomas replied that she was sleeping peacefully, and then added: "I have been married to her for ten years, and I still don't know who she really is. She has never been open with me."

This was not just a simple issue of marital miscommunication. Kate Jackson's identity—her background, her source of income, even her name—was ever-shifting. To her husband, she was an aristocrat born in a foreign land. To neighbors, she was a best-selling novelist and journalist. But to the local police, and soon a jury, she would become a murder case that has yet to be solved.

STRANGER THAN FICTION

The woman who would become Kate Jackson was born Kate Atkinson in the late 1880s to John Atkinson, a laborer in Lancaster, and his wife, Agnes. Sometime in her teens, she left Lancaster with a dream of becoming an actress on the London stage. She lived for a while with an artist named Leopold Le Grys, who later described her as uneducated, but "clever, and a good talker."

Never one to pass up an opportunity for the dramatic, she caught the attention of union official George Harrison in 1914 by fainting after witnessing a minor car accident on Charing Cross Road. She told him she hadn't eaten in three days, and so he took her to lunch. They became involved, and the next year she asked him for £40 for an abortion. Then she said there were complications from the procedure, so she needed more. For one reason or another—perhaps there were more procedures, perhaps she threatened to expose the affair, perhaps he was paying for her sexual services—Harrison sent her as much as £30 (over $4000 in 2018 dollars) a week over the course of a decade. All of it was embezzled through his position as the secretary of a cooper's union.

Harrison was far from the only man in Kate's life. When she met the man who would become her husband in 1919, Kate told him she was Madame Molly Le Grys, the Indian-born youngest daughter of the Duke of Abercorn. That wasn't all: She also said she was a writer under contract with publisher Alfred Harmsworth, an early-day Rupert Murdoch-type who pioneered tabloid-style journalism. It was a mutual deception, as he gave her a fake name of his own: Captain Harry-Gordon Ingram. Really, he was Thomas Jackson, a World War I veteran surviving on a pension.

The pair married later that year, and Thomas moved into Kate's palatial farmhouse in Surrey. Kate always seemed to have money—even after Harrison was put on trial in 1927 for embezzling £19,000 (over a million British pounds in today's dollars) from his union, £8000 of which reportedly went to Kate. She was called to give evidence at the trial, but was not identified; the police called her "Madame X," in hopes that she would return at least some of the money Harrison had stolen and given to her. (It's not clear what her husband thought about all this.)

Kate indeed signed over her beautiful house as restitution and moved with Thomas to a humble bungalow named Kenilworth. They adopted a daughter, Betty, whose origin was another of Kate's mysteries: She told Thomas that Betty was the illegitimate daughter of a lord, and he apparently asked no follow-up questions.

Though her setting was less rarefied, Kate was still behaving like a belle in a Gothic melodrama. She dressed in silk, her homes were luxuriously decorated, she tipped generously, and she spent more than her husband made in a week on her fresh flowers. The source of her income at this point is unclear: Harrison was serving a five-year prison stint, so he likely wasn't sending her cash any longer. But she was still receiving regular bundles of banknotes every Wednesday—money she may have earned through sex work, or possibly blackmail of other lovers/clients. Thomas later said that they mostly lived happily, except one time when she threw a flower pot at his head and threatened him with a knife for getting too friendly with Olive Dimick.

To Olive and her other neighbors, Kate explained the money by saying that she was a writer and the daughter of nobility. She let drop that she was secretly Ethel M. Dell, a well-known but critically reviled romance writer mocked by the likes of Orwell and Wodehouse. The real Dell was famously secretive; she was never interviewed and rarely photographed. So how were her neighbors supposed to fact-check their new friend? Besides, Dell's stories were quite racy, filled with passion and throbbing and exoticized visions of India, befitting Kate's made-up aristocratic origins.

"A PLEASANT SURPRISE"

Back at the hospital, Thomas Jackson left quickly, saying he had to return to his daughter. Kate spent six days there without ever fully regaining consciousness. When questioned about the identity of her attacker, she repeated the word Gorse, although it's not clear what—or who—she meant. She died on February 10, 1929, at the age of 43.

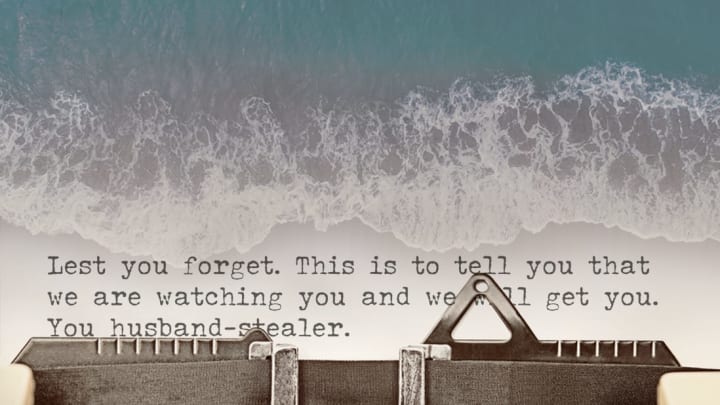

Police who arrived early in the morning after the attack found a tire iron under a cushion in the house, which Thomas later suggested Kate had hidden as a "pleasant surprise" (it's not clear if he was being ironic, or if he considered it a potential gift for his tool box). They also found a number of threatening letters. One read:

"Lest you forget. This is to tell you that we are watching you and we will get you. You husband-stealer. You robber of miner's money that would have fed starving children; you and that man of yours, I suppose he is somebody's husband, too. When we get you we will tar-and-feather you, and for every quid you have taken from us you will get another lump of tar and one more feather. We will show people you are as black outside as you are in. We don't mind doing quod [prison time] for you, you Picadilly Lily. We will get you yet."

It went on like that. Though he had been cooperative and there was no indication the letters were written by him, police arrested Thomas promptly. The next month he was charged with murder.

When the trial commenced in June 1929, the prosecution's theory was that Jackson, tired of his wife now that she was bringing in less money, had argued with and then attacked her as she was removing her coat. The prosecution pointed out that his story was weird—who hides a tire iron in a couch as a surprise?—and his behavior after her attack, including not summoning police immediately and not staying long at the hospital, was sketchy. They pointed to triangular cuts in her coat that looked like they could have been made with the tire iron. It was also alleged that all of the mystery in her life was entirely his creation, and that Kate never claimed to be anyone other than she was. The letters were ignored.

In his defense, Jackson produced expert witnesses who said it might not have been the tire iron that killed his wife. He spoke of her fear of attack after the threatening letters, saying that she was nervous to be left alone at night. Another neighbor, Rose Gammon, testified that Kate had been jumpy; Gammon recalled seeing Kate jump out of a bath, put on a robe, grab her gun, and walk out onto her dark veranda to investigate a noise (it's not clear if Gammon was spying on her neighbor, or how else she might have witnessed a bath).

The judge was firmly against Jackson, but during the trial, the fishmonger became a folk hero of sorts. He was charming and witty, playing up the grieving-single-father angle by emphasizing his concern for poor Betty. After just half an hour, the jury returned a verdict of "not guilty." The crowd went wild. As he left the courtroom after his verdict, a crush of women pressed upon Thomas, trying for a kiss.

The police never pursued any other leads, convinced that they had missed their shot at the true villain. And maybe they were right. Perhaps Kate's husband was her killer. Or perhaps it was a man who suffered from her blackmailing—"Gorse," or someone else. Perhaps it was a member of the union who felt she hadn't paid enough restitution. Kate Jackson had made a lot of enemies in her four decades, which helped make her death as mysterious and complicated and sad as her enigmatic life as Molly, and/or Kate, and/or Madame X; she was truly the stuff of the novels she never actually wrote.

Additional Sources: The Times of London: February 12, 1929; February 25-26, 1929; March 13-14, 1929; March 20-22, 1929, July 2-8, 1929; Still Unsolved: Great True Murder Cases; A-Z of Swansea: Places-People-History