In 1870, John Collins dreamed of a future without cigarettes, crime, or currency inflation. The Quaker poet, teacher, and lithographer authored "1970: A Vision for the Coming Age," a 28-page-long poem that imagines what the world would be like a century later—or, as Collins poetically puts it, in "nineteen hundred and threescore and ten.”

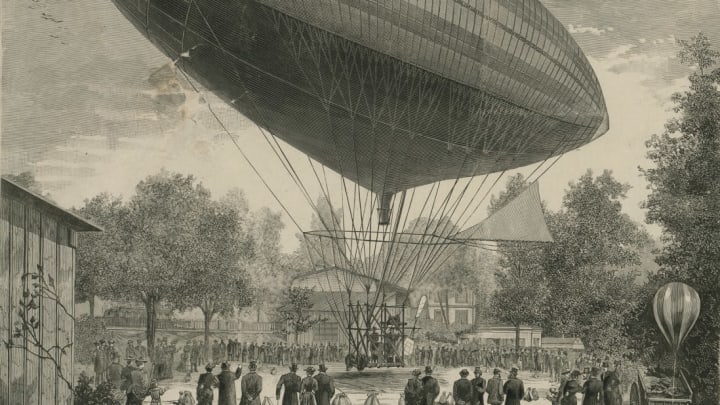

The poem, recently spotlighted by The Public Domain Review, is a fanciful epic that follows a narrator as he travels in an airship from Collins’s native New Jersey to Europe, witnessing the wonders of a futuristic society.

In Collins’s imagination, the world of the future seamlessly adheres to his own Quaker leanings. He writes: “Suffice it to say, every thing that I saw / Was strictly conformed to one excellent law / That forbade all mankind to make or to use / Any goods that a Christian would ever refuse.” For him, that means no booze or bars, no advertising, no “vile trashy novels,” not even “ribbons hung flying around.” Needless to say, he wouldn’t have been prepared for Woodstock. In his version of 1970, everyone holds themselves to a high moral standard, no rules required. Children happily greet strangers on their way to school (“twas the custom of all, not enforced by a rule”) before hurrying on to ensure that they don’t waste any of their “precious, short study hours.”

It’s a society whose members are never sick or in pain, where doors don’t need locks and prisons don’t exist, where no one feels tempted to cheat, lie, or steal, and no one goes bankrupt. There is no homelessness. The only money is in the form of gold and silver, and inflation isn't an issue. Storms, fires, and floods are no longer, and air pollution has been eradicated.

While Collins’s sunny outlook might have been a little off-base, he did hint at some innovations that we’d recognize today. He describes international shipping, and comes decently close to predicting drone delivery—in his imagination, a woman in Boston asks a Cuban friend to send her some fruit that “in half an hour came, propelled through the air.” He kind of predicts CouchSurfing (or an extremely altruistic version of Airbnb), imagining that in the future, hotels wouldn't exist and kind strangers would just put you up in their homes for free. He dreams up undersea cables that could broadcast a kind of live video feed of musicians from around the world, playing in their homes, to a New York audience—basically a YouTube concert. He describes electric submarines (“iron vessels with fins—a submarine line, / propels by galvanic action alone / and made to explore ocean’s chambers unknown") and trains that run silently. He even describes climate change, albeit a much more appealing view of it than we’re experiencing now. In his world, “one perpetual spring had encircled the earth.”

Collins might be a little disappointed if he could have actually witnessed the world of 1970, which was far from the Christian utopia he hoped for. But he would have at least, presumably, really enjoyed plane rides.

You can read the whole thing here.

[h/t The Public Domain Review]