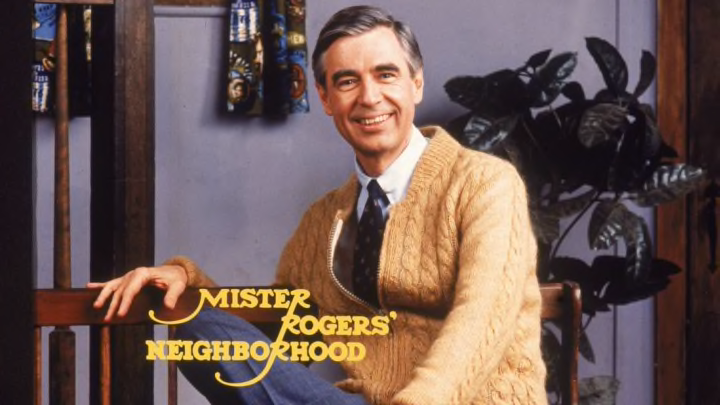

Mr. Rogers knew children well. He knew how they thought, what they liked, what they feared, and what they struggled to understand—and he went to great lengths to ensure he never upset or confused his devoted viewers.

Maxwell King, author of the forthcoming book The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers, writes in The Atlantic that Mr. Rogers carefully chose his words while filming Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. He understood that children think in a literal way, and a phrase that might sound perfectly fine to adult ears could be misinterpreted by younger audiences.

During filming, a nurse shown inflating a blood-pressure cuff originally said, “I’m going to blow this up.” Mr. Rogers decided to edit the line in post-production, according to Arthur Greenwald, a former producer of the show. “Fred made us re-dub the line, saying, ‘I’m going to puff this up with some air,’ because ‘blow it up’ might sound like there’s an explosion, and he didn’t want the kids to cover their ears and miss what would happen next,” Greenwald told King.

Rogers was “extraordinarily good at imagining where children’s minds might go,” King said, adding that Mr. Rogers wrote a song called “You Can Never Go Down the Drain” because he knew this might be a fear shared by many children.

In 1977, Greenwald and writer Barry Head dubbed this careful manner of speaking “Freddish,” and even created an illustrated manual outlining Rogers’s code under the title “Let’s Talk About Freddish.” The show's dialogue went through nine rigorous steps of editing before Rogers approved it for broadcast. Those steps, excerpted from King’s book, are as follows:

1. “State the idea you wish to express as clearly as possible, and in terms preschoolers can understand.” Example: It is dangerous to play in the street. 2. “Rephrase in a positive manner,” as in: It is good to play where it is safe. 3. “Rephrase the idea, bearing in mind that preschoolers cannot yet make subtle distinctions and need to be redirected to authorities they trust.” As in: Ask your parents where it is safe to play. 4. “Rephrase your idea to eliminate all elements that could be considered prescriptive, directive, or instructive.” In the example, that’d mean getting rid of ask: Your parents will tell you where it is safe to play. 5. “Rephrase any element that suggests certainty.” That’d be will: Your parents can tell you where it is safe to play. 6. “Rephrase your idea to eliminate any element that may not apply to all children.” Not all children know their parents, so: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. 7. “Add a simple motivational idea that gives preschoolers a reason to follow your advice.” Perhaps: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is good to listen to them. 8. “Rephrase your new statement, repeating the first step.” Good represents a value judgment, so: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them. 9. “Rephrase your idea a final time, relating it to some phase of development a preschooler can understand.” Maybe: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them, and listening is an important part of growing.

This attention to detail didn't just extend to language, either. Jim Judkis, who occasionally worked on the set of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood as a photographer, recalled a time when Rogers had videographers reshoot a scene in which the trolley ran from right to left instead of the other way around. Judkis was puzzled, so he asked the show's staff why this was necessary.

“They said, he’s very particular about consistency for a child,” Judkis told The Washington Post. “When you read, your eye tracks from left to right. He was trying to reinforce that.”

More details about the life of Fred Rogers will be revealed in King’s book, which will be released September 4. It is available for pre-order on Amazon.

[h/t The Atlantic]