For 22 years, Bostonians who wished a fellow colonist so much as a "Merry Christmas" would have to shell out five shillings for flaunting their Yuletide spirit. On May 11, 1659, Puritanical theocrats brought the hammer down on Christmas celebrations, enacting a political ban on the holiday and charging fines to Christmas sympathizers. The records of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's general court shed some light on just how the Puritans managed to shutter holiday celebrations, stating:

...It is therefore ordered by this court and the authority thereof that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shilling as a fine to the county.

The ban, enacted to put the kibosh on general holiday rowdiness—Reverend Increase Mather (pictured above), a New Englander and father of Salem Witch Trials figurehead Cotton Mather, denounced the holiday season as "consumed in Compotations, in Interludes, in playing at Cards, in Revellings, in excess of Wine, in Mad Mirth"—held steady through 1681.

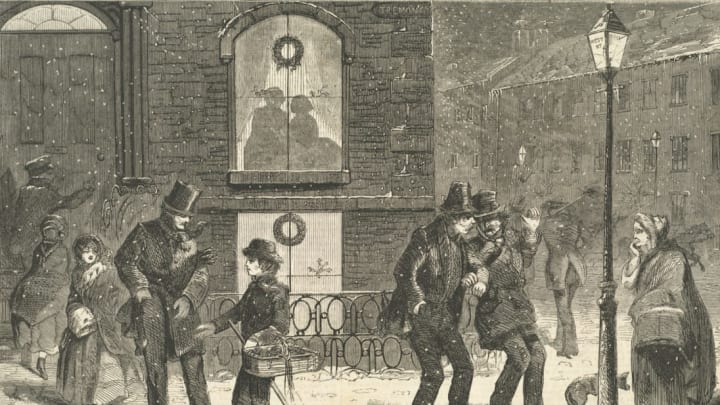

Christmas customs prior to the ban were a little more unruly than hanging wreaths and caroling. One popular tradition, called wassailing, involved lower class colonists demanding food and drink from citizens of wealthier stature in exchange for toasting their good health. If denied, proceedings often got violent.

Though Christmas wasn't officially banned until 1659, journals from the Puritans' first Christmas in the colony illustrate that the number of settlers who celebrated Christmas was split. By the second Christmas—after a sickness-plagued year—the holiday was already unofficially prohibited.

Puritan rule, which banned seasonal delicacies like mince pies and pudding, decreed working on Christmas as mandatory and dispatched town criers on Christmas Eve to shout "No Christmas, No Christmas" through the streets of Boston. The outlawing of Christmas was also a regional, purely Puritanian restriction—farther south, Jamestown settler John Smith reported that Christmas was "enjoyed by all and passed without incident."

Christmas returned to the Massachusetts Colony in 1681—sort of. When newly appointed royal governor Sir Edmund Andros (who also turned back a Puritan ban on Saturday night activities) sponsored and attended Christmas services in 1686, he was heavily guarded by a regiment of redcoats.

Bostonian judge Samuel Sewall kept a chronicle of how Christmas was celebrated in his native colony, noting that celebrations remained sparse. Wrote Sewall in a 1685 diary entry: "Carts come to Town and Shops open as is usual." Working was no longer a necessity on Christmas Day, but had become a staple after a 22-year lack of Yuletide traditions.

Celebrating Christmas in Boston stayed out of vogue through the mid-1800s; public school students caught skipping class on Christmas Day in 1869, the year before Ulysses S. Grant named Christmas a national holiday, still risked expulsion. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow put a poetic spin on Boston's Christmas cold spell in 1858, acknowledging the Puritanical footprint left on New England's holiday spirit.

We are in a transition state about Christmas here in New England. The old Puritan feeling prevents it from being a cheerful hearty holiday; though every year makes it more so.