Human civilization has changed a lot over the past five millennia—but our instinct toward fakery, fraud, and flimflam seems to have remained relatively stable. In their new book Hoax: A History of Deception (Black Dog & Leventhal), Ian Tattersall and Peter Névraumont sift through 5000 years of our efforts to con others with scams and shakedowns of every description, from selling nonexistent real estate to transatlantic time travel. This excerpt reveals a convoluted art heist that netted not one, but six, of Leonardo da Vinci's most famous portrait(s).

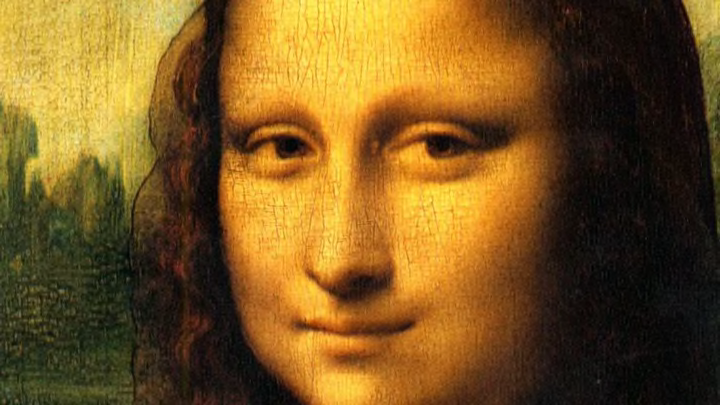

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is, by a wide margin, the world’s best-known Renaissance painting. The pride of Paris’s Louvre museum, it is hard nowadays for a visitor to get a good look at. Not only do heavy stanchions and a substantial velvet rope keep art lovers at bay, but a jostling horde of phone-pointing tourists typically accomplishes the same thing even more effectively. While you can expect to scrutinize Leonardo’s nearby Virgin and Child with Saint Anne up close and in reasonable tranquility, you are lucky to catch more than a glimpse of the Mona Lisa over the heads of the heaving crowd. And that’s just getting to admire the painting: With elaborate electronic protection and constantly circulating guards, stealing the iconic piece is pretty much unthinkable.

At a time when the standards of security were considerably more lax, around noon on Tuesday, August 22, 1911, horrified museum staff reported that the Mona Lisa was missing from her place on the gallery wall. The Louvre was immediately closed down and minutely searched (the picture’s empty frame was found on a staircase), and the ports and eastern land borders of France were closed until all departing traffic could be examined. To no avail. After a frantic investigation that temporarily implicated both the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and the then-aspiring young artist Pablo Picasso, all that was left was wild rumor: The smiling lady was in Russia, in the Bronx, even in the home of the banker J.P. Morgan.

Two years later the painting was recovered after a Florentine art dealer contacted the Louvre saying that it had been offered to him by the thief. The latter turned out to have been Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian artist who had worked at the Louvre on a program to protect many of the museum’s masterworks under glass.

Peruggia reportedly told police that, early on the Monday morning before the theft was discovered—a day on which the museum was closed to the public—he had entered the Louvre dressed as a workman. Once inside, he had headed for the Mona Lisa, taken her off the wall and out of her frame, wrapped her up in his workman’s smock, and carried her out under his arm. Another version has Peruggia hiding in a museum closet overnight, but in any event the heist itself was clearly a pretty simple and straightforward affair.

Peruggia’s motivations appear to have been a little more confused. The story he told the police was that he had wanted to return the Mona Lisa to Italy, his and its country of origin, in the belief that the painting had been plundered by Napoleon—whose armies had indeed committed many similar trespasses in the many countries they invaded.

But even if he believed his story, Peruggia had his history entirely wrong. For it had been Leonardo himself who had brought the unfinished painting to France, when he became court painter to King François I in 1503. After Leonardo died in a Loire Valley château in 1519, the Mona Lisa was legitimately purchased for the royal collections.

So it didn’t seem so far-fetched when, in a 1932 Saturday Evening Post article, the journalist Karl Decker gave a significantly different account of the affair. According to Decker, an Argentinian con man calling himself Eduardo, Marqués de Valfierno, had told him that it was he who had masterminded Peruggia’s theft of the Mona Lisa. And that he had sold the painting six times!

Valfierno’s plan had been a pretty elaborate one, and it had involved employing the services of a skilled forger who could exactly replicate any stolen painting—in the Mona Lisa’s case, right down to the many layers of surface glaze its creator had used. By Decker’s account, Valfierno not only sold such fakes on multiple occasions, but used them to increase the confidence of potential buyers, ahead of the heist, that they would be getting the real thing after the theft.

The fraudster would take a victim to a public art gallery and invite him to make a surreptitious mark on the back of a painting that he had scheduled to be stolen. Later Valfierno would present him with the marked canvas, which had allegedly been stolen and replaced with a copy.

This trick was actually accomplished by secretly placing the copy behind the real painting, and removing it after the buyer had applied his mark. According to Valfierno, this was an amazingly effective sales ploy: So effective, indeed, that by his account he managed to pre-sell the scheduled-to-be-stolen Mona Lisa to six different United States buyers, all of whom actually received copies.

Those copies had been smuggled into America prior to the heist at the Louvre, when nobody was on the lookout for them, and the well-publicized theft itself served to validate their apparent authenticity when they were delivered to the marks in return for hefty sums in cash.

According to Valfierno, the major problem in all this turned out to be Peruggia, who stole the stolen Mona Lisa from him and took it back to Italy. Still, when he was caught trying to dispose of the painting there, Peruggia could not implicate Valfierno without compromising his own story of being a patriotic thief, so the true scheme remained secret. Similarly, when the original Mona Lisa was returned to the Louvre, Valfierno’s buyers could assume that it was a copy—and in any case, they would hardly have been in a position to complain.

Decker’s story of Valfierno’s extraordinary machinations caused a sensation, and it rapidly became accepted as the truth behind the Mona Lisa’s disappearance. Perhaps this is hardly surprising because, after all, Peruggia’s rather prosaic account somehow seems a little too mundane for such an icon of Renaissance artistic achievement. The more flamboyant Valfierno version was widely believed, and is still repeated over and over again, including in two recent books.

Yet there are numerous problems with Decker’s Saturday Evening Post account, including the fact that nobody has ever been able to show for certain that Valfierno actually existed (though you can Google a picture of him). Only Peruggia’s role in the disappearance of the Mona Lisa seems to be reasonably clear-cut. Still, although it remains up in the air whether Valfierno faked his account, or whether Decker fabricated both him and his report, the Mona Lisa that hangs in the Louvre today is probably the original.