Mythological mountain ranges, illusory oceans, and apocryphal islands crowded the maps of early navigators. Some imaginary features, though, remained on charts well after satellite imagery and GPS should have confirmed their nonexistence. As Edward Brooke-Hitching writes in his new book, The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies, and Blunders on Maps (Chronicle Books), some fake places made a lasting impression simply because their promoters were so brazen. In this excerpt, Brooke-Hitching describes one scoundrel's scheme to lure settlers to a fictional Central American city of untold riches—with disastrous results.

There are shameless liars, there are bold-as-brass fraudsters, and then there is a level of mendacity so magnificent it is inhabited by one man alone: ‘Sir’ Gregor MacGregor. In 1822, South American nations such as Colombia, Chile, and Peru were a new vogue in a sluggish investor’s market, being lands of opportunity, offering bonds with rates of interest too profitable to pass up. And so, when the charismatic ‘Cazique of Poyais’ sauntered into London, resplendent in medals and honors bestowed on him by George Frederic Augustus, king of the Mosquito Coast, and waving a land grant from said monarch that endowed him his own kingdom, he was met with an almost salivary welcome.

Perhaps if he had been a total stranger there might have been more wariness, but this was a man of reputation: Sir Gregor MacGregor of the clan MacGregor, great-great-nephew of Rob Roy, was famous from overseas dispatches for his service with the ‘Die-Hards,’ the 57th Foot regiment that had fought so valiantly at the Battle of Albuera in 1811. As a soldier of fortune, he had bled for Francisco de Miranda and for Simón Bolívar against the Spanish; the man was a hero. And now here he was in London, fresh from adventure, with the glamorous Princess Josefa of Poyais on his arm, looking for investment in his inchoate nation.

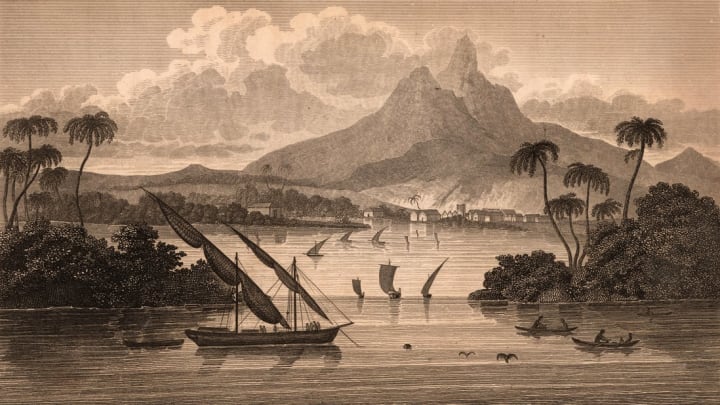

And the tales he told of his new homeland! Some 8 million acres (3.2 million hectares) of abundant natural resources and exquisite beauty; rich soil crying out for skilled farming; seas alive with fish and turtles, and countryside crowded with game; rivers choked with ‘native Globules of pure Gold.’ A promotional guide to the region was published, Sketch of the Mosquito Shore: Including the Territory of Poyais (1822), featuring the utopian vista below and further details of ‘many very rich Gold Mines in the Country, particularly that of Albrapoyer, which might be wrought to great benefit.’ Best of all, for a modest sum you too could claim your own piece of paradise.

For a mere 2 shillings and 3 pence, MacGregor told his rapt audience, 1 acre (0.4 hectares) of Poyais land would be theirs. This meant that, if you were able to scrape together just over £11, you could own a plot of 100 acres (40 hectares). Poyais was in need of skilled labor—the plentiful timber had great commercial potential; the fields could yield great bounty if worked properly. A man could live like a king for a fraction of the British cost of living. For those too ‘noble’ for manual labor, there were positions with prestigious titles available to the highest bidder. A city financier named Mauger was thrilled to receive the appointment of manager of the Bank of Poyais; a cobbler rushed home to tell his wife of his new role as official shoemaker to the Princess of Poyais. Families keen to secure an advantage for their young men purchased commissions in Poyais’s army and navy.

MacGregor himself had got his start this way in the British Army at the age of 16, when his family purchased for him a commission as ensign in 1803, at the start of the Napoleonic Wars. Within a year he was promoted to lieutenant, and began to develop an obsession with rank and dress. He retired from the army in 1810 after an argument with a superior officer ‘of a trivial nature,’ and it was at this point that his imagination began to take a more dominant role in his behavior. He awarded himself the rank of colonel and the badge of a Knight of the Portuguese Order of Christ. Rejected from Edinburgh high society, in London he polished his credentials by presenting himself as ‘Sir Gregor MacGregor.’ He decided to head for South America, to add some New World spice to his reputation and return a hero. Arriving in Venezuela, by way of Jamaica, he was greeted warmly by Francisco de Miranda and given a battalion to help fight the Spanish in the Venezuelan War of Independence. He then fought for Simón Bolívar when Miranda was imprisoned. Operations extended to Florida, where he devised a nascent form of what he was later to orchestrate in London, raising $160,000 by selling ‘scripts’ to investors representing parcels of Floridian territory. As Spanish forces closed in, he bid farewell to his men and fled to the Bahamas, never repaying the money.

MacGregor was intelligent, persuasive, charisma personified, with a craving for popularity, wealth, and acceptance of the elite. This was the man to whom the prospective Poyais colonists were faithfully handing their every penny. Every detail of his scheme was planned to perfection. They never stood a chance.

On September 10, 1822, the Honduras Packet left London docks, bound for the territory of Poyais, carrying 70 excited passengers, plenty of supplies and a chest full of Poyais dollars made by the official printer to the Bank of Scotland, for which the emigrants happily traded their gold and legal tender.

Having waved off the Honduras, MacGregor headed to Edinburgh and Glasgow to make the same offer to the Scots. The dramatic failure of the Darien scheme in the late 17th century (in which the kingdom of Scotland had attempted to establish a colony on the Isthmus of Panama) had virtually bankrupted the country, and any indication of history repeating itself would have been met with extreme caution. But MacGregor was a Scotsman himself, a patriot and soldier. Unfortunately, he was also in possession of a tongue of pure silver. A second swath of Poyais real estate was sold off, and a second passenger ship filled. Under the captaincy of Henry Crouch, the Kennersley Castle left the port of Leith, Scotland on January 14, 1823, carrying 200 future citizens of Poyais, eager to join the Honduras Packet travelers in their new home.

To their utter confusion, when the colonists arrived at their destination, they found only malarial swampland and thick vegetation with no trace of civilization. There was no Poyais, no land of plenty, no capital city. They had been fooled by a conniving fantasist. Unable to afford the journey home, they had no choice but to unload their supplies and set up camp on the shore. By April, nothing had changed. No town had been found, no help had arrived, and the camp was in total despair. Disease was rife and claimed the lives of eight colonists that month. The cobbler who had been promised the role of ‘Shoemaker to the Princess’ gave up hope of ever seeing his family again, and shot himself in the head.

At this lowest point, a vessel appeared on the horizon—what’s more, it flew a British flag. The Mexican Eagle from Belize had been passing nearby on a diplomatic mission when it had caught sight of the camp. The weak settlers were brought aboard and began their slow and awful journey back to London, via the hospitals of Belize. Of the 270 or so men and women who had set out for Poyais, fewer than 50 made it back to Britain. By this time MacGregor had high-tailed it to France, where he tried and failed to run the scam again. (He was foiled when the French government noticed the rush of applications for visas to a country that didn’t exist.) He was eventually forced to flee to Venezuela, where he later died in 1845, never properly brought to answer for his extraordinary and terrible crime.

From The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps, by Edward Brooke-Hitching, published by Chronicle Books.