A newspaper once said that "there never was a more audacious experiment in marine architecture" than the R.M.S. Lusitania. But on May 7, 1915, a German torpedo sunk the massive ship, killing more than 1100 civilian passengers. The sinking was one of the events that nudged the U.S. into World War I. Read on for more facts about this legendary ocean liner.

1. The Lusitania was meant to help Britain regain economic power.

The Liverpool-based shipping company Cunard ordered the R.M.S. Lusitania and its sister ship, the R.M.S. Mauretania, in 1902, and the Lusitania was built by the shipyard of John Brown & Co. in Scotland. For Cunard, the two ocean liners had a shared purpose: to restore Britain’s dominance in the transatlantic passenger travel industry by beating its German (and, to a lesser degree, American) competition. At the start of the 20th century, German ocean liners had the finest amenities and latest onboard technology, and had held the record for the fastest Atlantic crossings since 1897. Cunard bet that its two new “superliners” could reach unheard-of speeds and breathe new life into British travel.

2. Cunard was given a huge loan—with a catch.

To build the Lusitania and Mauretania, Cunard secured a £2.6 million, low-interest subsidy from the British government (in today’s currency, that’s about £300 million). Cunard also received an annual operating subsidy of £75,000, or about £8.6 million today, for each ship, and a contract worth £68,000 each, or £7.8 million today, to transport mail. (The “R.M.S.” in their names stands for “royal mail ship.”)

What would the British government get out of the deal, besides national pride and a very low return on investment? The Admiralty required that both ships would be built to naval specifications so they could be requisitioned for use in war. While the Lusitania never ferried troops, the Mauretania was put into service as a hospital ship and as a troopship, and even got a coat of dazzle paint to camouflage it at sea.

3. The Lusitania included cutting-edge Edwardian technology.

As another part of the loan deal, Cunard guaranteed that both ships would be able to cruise at a speed of at least 24.5 knots (about 28 mph): That would make the Lusitania and Mauretania faster than the speediest German liners, which could run just over 23 knots.

To meet the challenge, Cunard installed four steam turbine engines, each with its own screw propeller, a first for ocean liners. The new technology in the Lusitania required “68 additional furnaces, six more boilers, 52,000 square feet of heating surface, and an increase of 30,000 horsepower,” The New York Times reported. Without the turbines, the ship would have needed at least three 20,000-horsepower standard engines to reach 25 knots.

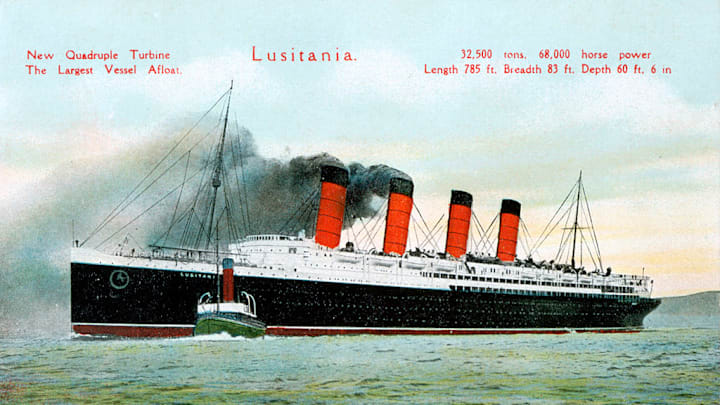

The Lusitania needed all of the power it could get, because it was massive: 787 feet long, with a gross tonnage of around 32,000 tons, four funnels to match the Germans’ look (previous British liners had three), and seven passenger decks. The ship was designed to accommodate 563 first-class, 464 second-class, and 1138 third-class passengers, plus 802 crew.

4. Thousands watched the Lusitania depart on its maiden voyage.

On September 7, 1907, the Lusitania departed Liverpool on its maiden voyage en route to New York with a stop in Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland. “She presented an impressive picture as she left with her mighty funnels and brilliant illuminations,” the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser reported. “Throughout the day there was a continuous stream of sightseers on board, and the departure was witnessed by about 200,000 people.”

When the ship reached Queenstown, the paper continued, “768 bags of mail were put on board the Lusitania, which, amid enthusiastic cheers from the crowds of spectators attracted from all parts of the Emerald Isle, set off her great trial of speed across the broad Atlantic.”

5. Even third-class passengers traveled in style.

Each class of passenger accommodation featured dining rooms, smoking rooms, ladies’ lounges, nurseries, and other public spaces. They ranged in opulence from plush Georgian and Queen Anne styles in the first-class compartments to plain but comfortable in third class. The Lusitania was also the first ocean liner to have elevators, as well as a wireless telegraph, telephones, and electric lights.

Onboard dining included dozens of dishes at each seating for the most discerning Edwardian gastronomes. A luncheon menu from January 1908 suggested appetizers like potted shrimps, omelette aux tomates, lamb pot pie, and grilled sirloin steak or mutton chops. A variety of cold meats—Cumberland ham, roast beef, boiled ox tongue, boar’s head, and more—was served next. For dessert, guests could nibble on fancy pastry, compote of prunes and rice, cheeses, fruits, and nuts.

6. The Lusitania regained the Blue Riband.

Germany’s dominance in transatlantic service pained Britain, the country that basically invented the race for ever-faster crossings. Cunard desperately wanted to win back the Blue Riband, an unofficial title for the fastest average time on a crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, from the German superliners. Bad weather prevented the Lusitania from reaching its top speed on the first try. But on the voyage from October 6-10, 1907, the ship reached an average speed of 23.99 knots, smashing the German’s record.

The Lusitania broke its own record, but lost it to the Mauretania in 1909, which held on to the Blue Riband for the next 20 years.

7. Lusitania passengers were warned about enemy attacks.

The First World War broke out in Europe in July 1914. On May 1, 1915—the day of the Lusitania’s fateful departure—the German embassy in Washington, D.C., published a note in New York’s morning newspapers reminding passengers of the danger of transatlantic travel during the war. In some papers, the announcement appeared directly under an advertisement for Cunard’s future sailings, including the Lusitania’s scheduled trip on May 29, 1915. “Notice! Travellers [sic] intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies,” it shouted. “Vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in [British] waters and that travellers [sic] sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.”

Few believed the Lusitania was in danger, because it had sailed without incident since the beginning of the war. And, as a passenger ship carrying civilians, it was not thought to be a legitimate military target.

8. It was torpedoed by a German U-boat.

The first six days of the crossing were typically uneventful. In the early afternoon of May 7, able seaman Leslie Morton began his scheduled watch at 2 p.m. He told the BBC:

“It was a beautiful day; the sea was like glass. And as we were going to be in Liverpool the next day, everybody felt very happy. We hadn’t paid a great deal of attention to the threats to sink her because we didn’t think it was possible … Ten past two, I saw a disturbance in the water, obviously the air coming up from a torpedo tube. And I saw two torpedoes running toward the ship, fired diagonally across the course. The 'Lucy' was making about 16 knots at the time. I reported them to the bridge with a megaphone, we had torpedoes coming on the starboard side. And by the time I had time to turn round and have another look, they hit her amidships between No. 2 and 3 funnels.”

In first class, the suffragette and businesswoman Margaret Haig Thomas (later Second Viscountess Rhondda) felt the impact. “There was a dull thud, not very loud, but unmistakably an explosion,” she told the BBC. “I didn’t wait; as I ran up the stairs the boat was already heeling over.”

9. The Lusitania sank in just 18 minutes.

The torpedo hit just behind the bridge (near the bow of the ship) and a huge cloud of smoke rose. Immediately, the ship began listing to the starboard side and the bow began to sink. Chaos ensued on the seven passenger decks. Morton told the BBC that all of the port-side lifeboats were now unable to be lowered to the water, while the starboard-side boats were filled with panicked passengers and let go haphazardly; some even capsized or fell on top of other boats already in the sea. Watching from his periscope, the U-boat’s captain Walther Schwieger wrote in his war diary, “Many people must have lost their heads; several boats loaded with people rushed downward, struck the water bow or stern first and filled at once.”

Moments after the torpedo hit, another blast exploded from inside the ship. At that point, the sea filled with people, lifeboats, splintered pieces of the ship, luggage, deck chairs, and other debris, all at risk of being sucked into the wake of the rapidly sinking ocean liner. “The whole thing was over in 15 minutes. It takes longer to tell,” recalled Morton, who had managed to find a collapsible boat and save dozens of other passengers. An hour later, he said, “the ship was already down at the bottom.”

Survivors and dead bodies were plucked from the water by fishermen in small boats, then taken to Queenstown. Of the 1960 verified people on board the Lusitania, 1193 were killed, and just 767 survived. Four of those survivors would soon die from trauma.

10. The sinking may have turned the tied of World War I.

Almost all of the American passengers—more than 120 of 159 on board—did not survive the sinking. The U.S., a neutral country, immediately criticized the attack on civilians, and public opinion turned against Germany and its actions. While Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan argued that Germany and Britain (which enforced a blockade of food shipments to Germany) were both worthy of blame in the disaster, the American people were choosing a side. The U.S. did not enter World War I, however, until April 1917.

11. The source of the second explosion remains a mystery.

In his testimony for the official investigation into the attack, Morton insisted that he witnessed two torpedoes launched at the Lusitania. Schwieger’s log and the U-boat crew’s accounts indicate the submarine fired only one.

The cause of the second explosion, 15 seconds after the first strike, is still unknown—but numerous theories abound. One suggests that undeclared explosives meant for the British military, stored in the ship’s magazine, detonated from the torpedo’s impact. Robert Ballard, who discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985, suggested in his book Lost Liners that the torpedo breached the ship’s coal bunkers and kicked up enough coal dust to trigger the blast. There is also a possibility that another, unidentified submarine fired a second torpedo, but no other sub ever took credit for the fatal blow, perhaps due to the global backlash against Schwieger’s action.

Maritime archaeologists may never know the truth. Three hundred feet down on the seafloor, the Lusitania wreck lies on the side that the torpedo breached, and many of the decks have collapsed onto the seabed, obscuring further clues.

12. The last Lusitania survivor passed away in 2011.

Audrey Warren Pearl was only 3 months old when she sailed on the Lusitania with her parents, three older siblings, and two nannies in first class. After the explosions and while attempting to board lifeboats, Audrey, her 5-year-old brother Stuart, and her nanny Alice Lines were separated from her sisters Amy and Susan, their nanny Greta Lorenson, and her parents, Warren and Amy Pearl. Alice and the two children were able to safely board Lifeboat 13, while Audrey’s parents were picked up from the sea and survived. Greta and the other two children were never found.

Audrey went on to be active in Britain’s war effort in the 1940s and in numerous charities. She and Alice Lines remained friends until Alice’s death in 1997 at the age of 100. Audrey, the last survivor of the 1915 disaster, lived to the age of 95 and died January 11, 2011.

A version of this story originally ran in 2018.