In the early days of exploration, scientists and species seekers had to rely on illustrations—often drawn from written descriptions or based on dead specimens—to bring their discoveries to life. Given their varied source material, “it’s remarkable how many illustrations were correct,” says Tom Baione, Harold Boeschenstein Director of the Department of Library Services at the American Museum of Natural History and editor of Natural Histories: Extraordinary Rare Book Selections from the American Museum of Natural History Library. But sometimes, an artist’s depiction of a creature was a little off, as you can see from the examples below. (A few of these illustrations are currently featured in an exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History inspired by its namesake book.)

1. Octopus

© AMNH\D. Finnin

This cephalopod appeared in Conrad Gessner’s Historia Animalium, a five-volume series published between 1551 and 1558. “The thing that always freaks me out about the octopus is just how well it’s figured,” Baione says. For printing, an artist would have taken a sketch and transferred it onto a woodblock—a very difficult task. “The idea that somebody could carve away all the wood and just leave tiny wooden slivers to represent these delicate lines delineating the animal—just the idea of doing that sounds complicated,” Baione says. But one tiny thing about the octopus is off: Cephalopods have horizontal pupils, regardless of their orientation. This indicates that the artist probably sketched the likeness of the animal from a dead specimen.

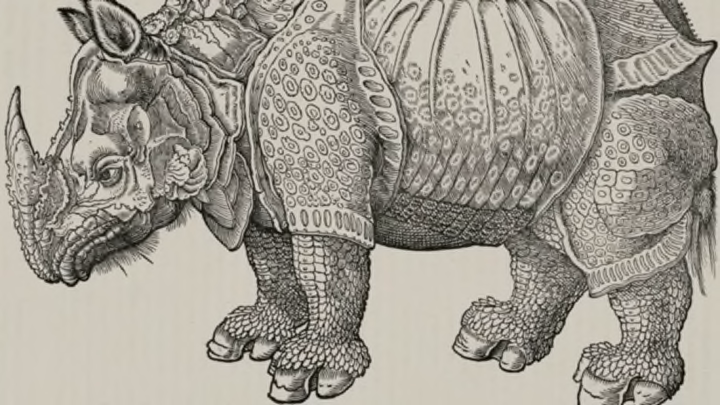

2. Rhinoceros

© AMNH\D. Finnin

Gessner worked with a number of different artists to create images for his Animalium volumes, and in some cases, used pre-existing woodcuts, including this one created by Albrecht Dürer in 1515. Of course, Durer and Gessner probably never actually saw a rhinoceros. “A visual game of telephone is, to some degree, what the artists were dealing with in the 16th century,” Baione says. “Durer may have worked from other artists' renditions and some written or verbal information about what the rhino’s prominent features were. If you look at a real rhinoceros, especially if you see it move, its body does look like it has plates hanging on it. It’s not so remarkable to think that someone might’ve been given information that led to the creation of the image that was made into a woodblock.”

As time went by, the artistic renderings of rhinos in natural history books got more realistic: “More people [were] seeing it and saying, ‘Oh, it doesn’t have a horn up there,’” Baione says. “‘It doesn’t have a beard. Its legs aren’t really like that. Its tail doesn’t have so much hair on it. It really has two horns, not just one horn. The horn’s not scaly. The ears are smaller.’ So eventually, it was refined until it was a much more realistic illustration. And before long, specimens of rhinos—living and preserved—made their way to Europe.”

3. Walrus

Wikimedia Commons

This sketch, also from Gessner’s Historia Animalium, is another good example of what happens when things get lost in translation. “We know that a walrus is a four-limbed creature,” Baione says. “So they show him with four limbs, but I guess because the description from someone who had seen one didn’t make it intact to the artist, these fins are figured in Gessner as separate from the four limbs, rather than part of the limbs.” The sketch of the walrus (which doesn’t appear in the book Natural Histories or the exhibition) is extraordinary for another reason: The walrus is an Arctic creature and, at that time, “there was not a lot of Arctic exploration going on,” Baione says. “A lot of people who saw arctic animals were on a one-way trip, if you know what I mean. It’s amazing that at that date, news of such a creature made its way all the way down to Switzerland, to Zurich, where Gessner worked.”

4. Puffer Fish

© AMNH\D. Finnin

These sketches, which appeared in Louis Renard’s 1719 book Poissons, écrevisses et crabes, de diverses couleurs et figures extraordinaires were drawn by artists from specimens. The artists purposefully embellished the fish with vibrant colors, strange patterns, and human-like expressions. The puffer fish appears almost angry. “I really like the expression on the puffer fish,” Baione says. “Appreciating his unusual features takes a closer look – which is what this exhibit allows– the book illustrations are greatly enlarged, making it easier to see his subtle expression and coloring—he looks like he’s going to jump off the page and perhaps bite you!”

5. Mandrill

© AMNH\D. Finnin

This illustration, which appeared in Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber’s 19th century book Mammals Illustrated From Nature, With Descriptions, is fairly accurate—but still posed in a very human, non-monkey-like way. “We hoped the mandrill shows how anthropomorphized these images were,” Baione says. “Some of them are almost laughably anthropomorphized, so we opted not to include them. We thought the mandrill was handsome and colorful, with his sensitive, wise expression.” The primate may also have a case of man hands. “His hands should’ve been a little more like his feet in the illustration, but so it goes,” Baione says. “It looks like the mandrill impersonator forgot his mandrill gloves.”

6. Two-Toed Sloth

© AMNH\D. Finnin

This illustration comes from Albert Seba’s four volume Thesaurus, published in the 18th century. “Seba worked in Amsterdam and he’s most famous for his collecting,” Baione says. “He was an apothecary, so he was looking to obtain and identify natural substances—either the gallbladder of a lizard or the seed of some plant—and by experimenting with them, he was able to create salves and tinctures and ointments that might relieve symptoms of illnesses—or, just as likely, make them worse.”

Seba would head down to the docks and barter with sick, returning sailors, trading his cures for their unusual specimens, which probably included this two-toed sloth. Because Seba’s artists were drawing from preserved specimens and live animals, they could generally accurately depict anatomical features, but not behaviors—this sloth is shown moving through the trees upright, while in reality, sloths hang upside down.

This armchair naturalism had other drawbacks, too: “People off in the far corners of the world knew, by the 18th century, that these funny bearded European characters loved strange stuff,” Baione says. “If you could show them something that you knew they hadn’t seen before—because you created it—then they might pay a high price or be very happy and reward you in some way. In some cases, Seba collected and illustrated a lot of creatures that we know didn’t and couldn’t have existed.”