A Brief History of the First French Encyclopedia

In the mid-1700s, a pair of French writers set out to organize all human knowledge. They called their project the Encyclopédie, and it was a translation and massive expansion of the English Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. Denis Diderot was the driving force behind the project, and was accompanied by Jean le Rond d'Alembert until 1759.

The project was insanely vast, and raised substantial questions that still challenge scholars today: How do you categorize and classify knowledge? Should the arts be presented alongside the sciences? How exactly can a reader navigate a 20,000,000-word collection of information? Hardest of all was how to print the thing and not be imprisoned.

Diderot's encyclopedia was almost insanely vast. It incorporated more than 70,000 entries, including original work from Voltaire, Rousseau, and other luminaries of the French Enlightenment. Many writers contributed massive amounts of labor, almost all of it unpaid, spanning three decades.

Louis XV and Pope Clement XIII both banned the thing, though Louis kept a copy, and apparently actually did read it. Because of political and religious pressure in France, Diderot and his compatriots had to smuggle pages out of the country in order to publish them. Collecting human knowledge wasn't just an academic exercise—it was also political.

Diderot explained his goal like so (translated from the original French in an entry on the Encyclopédie itself):

The goal of an encyclopedia is to assemble all the knowledge scattered on the surface of the Earth, to demonstrate the general system to the people with whom we live, and to transmit it to the people who will come after us, so that the works of centuries past is not useless to the centuries which follow, that our descendants, by becoming more learned, may become more virtuous and happier, and that we do not die without having merited being part of the human race.

Well said.

TED-Ed produced a terrific video history of the encyclopedia. Have a look:

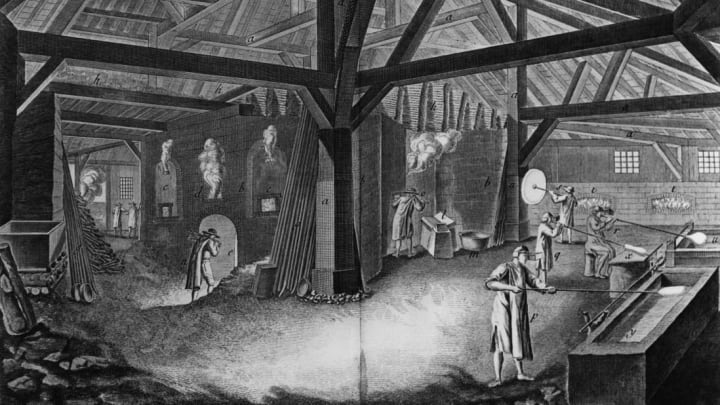

If you find that even remotely interesting, you'll love this online version of the encyclopedia hosted by the University of Michigan Library. It includes an excellent search engine, translations, and scans of the original pages—including illustration plates. If you're looking for a starter entry, read the entry entitled History (originally Histoire) written by Voltaire, which attempts to explain the history of history, at least from the perspective of an 18th-century French philosopher. Here's a snippet from the conclusion:

The method suitable to [the writing of] the history of your country does not [require] you to write on the discoveries of the new world. You should not write about a village as you would about a great empire; you should not write of the life of an individual as you would write the history of Spain or England. These rules are well known. But the art of writing History well will always be rare. It is well known that one must have a grave, pure, varied, agreeable style. There are laws for writing History just as there are laws for all the arts of the mind. There are many precepts and yet so few great artists.