You Could Once Buy “Memento Kits” Made of White House Scraps

The White House may be rather gilded these days, but when Harry Truman moved into the Executive Mansion in 1945, the place was anything but luxurious—in fact, it was literally falling apart.

Truman often wrote letters to friends and family romanticizing the creaks and drafts in his new home, imagining they were his feuding predecessors: “The floors pop and the drapes move back and forth. I can just imagine old Andy and Teddy having an argument over Franklin," he wrote to his wife Bess in 1945.

But the problems went well beyond creaky floorboards. By 1947, the First Family noticed chandeliers swinging and entire floors swaying “like a ship at sea.” In 1948, the leg of one of Margaret Truman’s pianos broke through the floor. Not long after, the Trumans moved across the street to Blair House while the White House was completely gutted, leaving only the original walls remaining. But Truman was exceedingly careful about keeping the integrity of those walls: Though the demolition of the interior required the use of a bulldozer, Truman forbade engineers from cutting a hole in the walls big enough to allow the machinery through. Instead, the bulldozer was disassembled and moved inside in pieces, then reassembled.

As you may imagine, the demolition phase produced literally tons of debris, which the public wanted a piece of—the White House was inundated with more than 20,000 requests for various bits and pieces, including wallpaper, burned wood, and doorknobs. In response, the Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion decided to make 13 different “authenticated memento kits” available to the public, an endeavor that netted an extra $10,000 toward renovations.

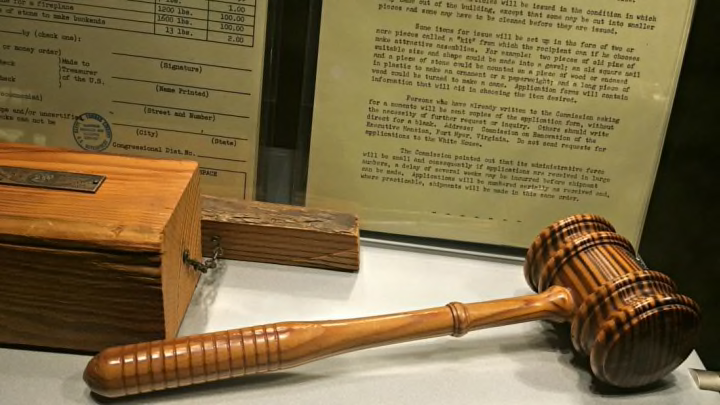

Souvenir-hunters could request everything from a “small piece of old metal” to “enough stone for a fireplace”—and all they had to pay were the shipping and processing costs. At $2.00, kit #1 (“Enough old pine to make a gavel”) was one of the most popular requests, with 5059 sold. “One brick, as nearly whole as practicable,” was $1.00, though this customer still had to pay 23 cents for shipping upon arrival.

“Two pieces of stone to make bookends” were $2.00; 2208 of them were purchased. This particular set, seen at the Truman Library and Museum, was made from two plaster cornice moldings.

For those interested in making White House remnants a larger part of their homes, 1600 pounds of stone suitable for a fireplace went for a mere $100.

Harry Truman himself was able to snag a chunk of fireplace memorabilia, though his was certainly worth more than $100. In 1902, Teddy Roosevelt decked out the State Dining Room with a stone mantel, a piece designed to complement the big-game trophies displayed on the walls. The mantel featured intricate carvings of buffalo heads, and in 1940, a prayer written by John Adams during his first night at the White House was added to the front.

Because it didn't fit the American-Georgian aesthetic of the reconstruction, the historic piece of architecture was “thrown out on the junk pile,” according to Truman. Official records, however, show that the mantel was never on the "junk pile"—it had been carefully placed in storage. Whatever the case may have been, Truman requested that the Buffalo Mantel be moved to Independence, Missouri, for inclusion in his Presidential Library. In 1962, during her quest to return historical furniture and other items to the White House, Jackie Kennedy wrote to the former president and requested that the mantel be returned home. Truman declined to send it back.

To this day, the original Buffalo Mantel remains at the Truman Library, and a replica adorns the State Dining Room fireplace at the White House.