More and more researchers are making new discoveries using old museum specimens. By digging through archives and collections, they've identified scores of new species, including the teddy bear–like olinguito and the Ruth Bader Ginsberg mantis.

Now, scientists examining cyanobacteria found during an expedition in Antarctica more than a century ago have made a surprising find: It looks an awful lot like the bacteria living there today. Their report on the bacteria’s stability appears in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

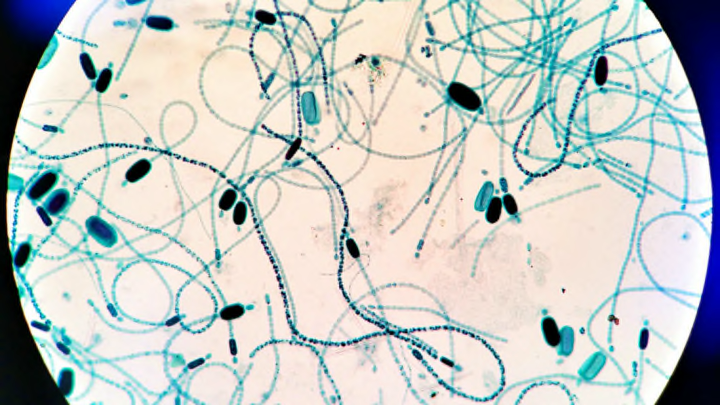

Cyanobacteria are itsy-bitsy organisms that have occupied Earth’s fresh and salt water for more than 3.5 million years. Also known (inaccurately) as blue-green algae, these single-celled microbes grow in clumps, balls, and sheets all over the world—even in the punishing cold of Antarctica.

The earliest expeditions to Antarctica had multiple goals, including scientific study. During the Discovery Expedition (1901–1904), Captain Robert Falcon Scott and his team fished a soggy mat of cyanobacteria from Lake Joyce. They brought the mat back to London’s Natural History Museum (NHM), where it was examined, pressed like a flower between sheets of paper, and shelved for safekeeping.

Fast-forward more than 100 years, and things aren’t looking so great for the Antarctic. Climate change is melting icecaps, changing the landscape, and altering plants’ and animals’ behavior and evolution. Researchers with NHM and the University of Waikato wondered if the same was true for the continent’s bacteria.

Anne Jungblut and Ian Hawes journeyed back down to Lake Joyce, where they used drills, cameras, and sediment traps to collect new cyanobacteria samples. Back in London, they retrieved Captain Scott’s algae mats from the archives. They compared the old and new samples, inside and out, scouring the mats for microbe fossils and sequencing their genes.

The results suggested that not much has been going on at Lake Joyce this past hundred years. The two groups of bacteria were remarkably similar, comprising the same species in the same proportions.

This could be good news, the researchers say. "We suggest that this relates to Antarctic freshwater organisms requiring a capacity to withstand diverse stresses," they write, "and that this could also provide a degree of resistance and resilience to future climatic-driven environmental change in Antarctica."

As genetic testing technology improves, museum-based discoveries like this one become more and more common. Biologist Evon Hekkala, of Fordham University, tells Mental Floss, "We are seeing time and time again (no pun intended!), that museum collections originally made for exploratory purposes can take on new and critical roles in helping us to understand the fine details of how living things are responding to our rapidly changing environment. They have helped in some cases to confirm that human activities are driving the loss of genetic diversity and in other cases to exonerate us. This paper is a nice example where we have a comparison across time that can help us to understand how resilient certain living things can be in the face of change. I always say that with museum collections time travel really is possible!"

Hekkala has herself made discoveries using museum specimens. She identified a new crocodile species lurking in the drawers of the American Natural History Museum (AMNH) when she took samples from two crocodile specimens collected from different sides of the Congo River, as she recounts in a recent episode of the AMNH video series Shelf Life: "I was dumbfounded when I looked at the DNA sequence. It turns out that one specimen represents the Nile crocodile species that we all know and love, and the other represents a completely separate species of crocodile. In fact, they’re so distinct that they’re not even each other’s closest relatives. They haven't exchanged genes in millions of years."

Hekkala says museum collections are more important than ever as climate change, deforestation, and habitat loss destroy our planet’s plants and animal populations: "These specimens represent an irreplaceable resource that can never be re-acquired."