Thousands of rarely seen Soviet children’s books are now available online. Playing Soviet: The Visual Languages of Early Soviet Children’s Books 1917-1953, a digital database, draws on Princeton University’s collection of 2500 Soviet picture books to create an interactive visual exhibition on the role of illustration and kid’s literature in the U.S.S.R. It includes digitized books with essays and annotations by scholars of Russian literature and history.

“In the selections featured here, the user can see first-hand the mediation of Russia’s accelerated violent political, social and cultural evolution from 1917 to 1953,” the website explains. “As was clear both from the rhetoric of the arbiters of Soviet culture—its writers and government officials—the illustration and look of Soviet children’s books was of tantamount importance as a vehicle for practical and concrete information in the new Soviet regime.”

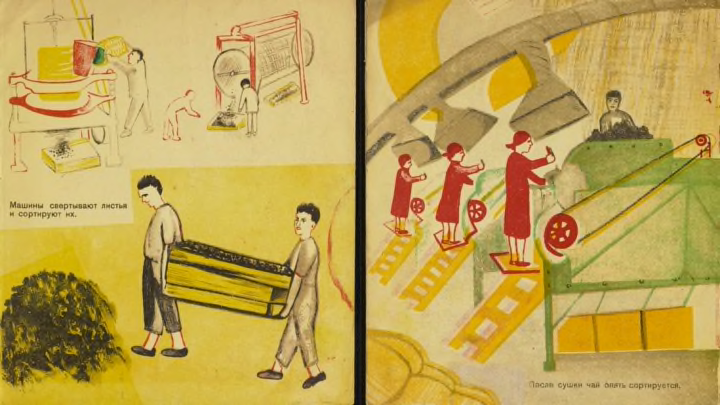

How the Revolution Was Victorious (Как победила революция) by Alisa Poret, 1930. Courtesy Princeton University

Many of the books were designed to indoctrinate children into the world of the “right” way to think about Soviet culture and history. For instance, in a book titled How the Revolution Was Victorious (Как победила революция), the overt aim of the publisher was to teach children born just after the October Revolution of 1917 what happened—namely, as Yuri Leving writes in the book’s analysis on the site, “to ensure the correct interpretation of the anti-governmental coup among the young generation of new Soviet readership.”

Youth, Go! (Юность, иди!) by A. Gastev and I. Shpinel, 1923. Courtesy Princeton University

This emphasis on children’s picture books as a tool for Soviet teachings elevated the role of the illustrator and artist in culture. Illustrators were considered on par with the great writers of the day and were given the opportunity to incorporate new, avant-garde styles into books for children and young adults.

Youth, Go! (Юность, иди!), a trade-union-commissioned manual on becoming an efficient worker, featured Cubo-Futurist and Constructivist illustrations that urged young people to become hyper-efficient machines, both mentally and physically.

The books included in Playing Soviet don’t include full English translations, but they are annotated to reveal important aspects of the artwork and the text. You can flip through the digital books or scroll through selections of individual pages from the whole collection. You can also search by artist, author, subject, year, or even color. The project is ongoing, and according to Princeton, the image database will add about 100 new images per year from now on.