Baby eels have joined the ever-growing club of animals that live their lives along magnetic lines. Researchers described these findings in the journal Scientific Advances.

Our planet and its inhabitants are shaped and impelled by invisible forces. Studies have found that foxes hunt and deer flee along north-south lines. Pigs and wild boars orient their nests to face the same way. Lobsters, butterflies, and whales all follow their internal compasses along magnetic lines. Adult European eels, too. But we weren’t really sure about their babies.

Grown-up European eels lay their many eggs in the Sargasso Sea. The eggs hatch into helpless larvae, which bob along in Atlantic currents. As the currents approach the continent, the babies transform again, this time into translucent miniature versions of their parents. These glass eels make their way into the coasts. From there, they swim inland to freshwater and bum around Europe and North Africa for five to 20 years. Finally, as adults, they head back to the sea to start the whole cycle all over again. It's one of the longest migrations in the animal kingdom, the researchers say.

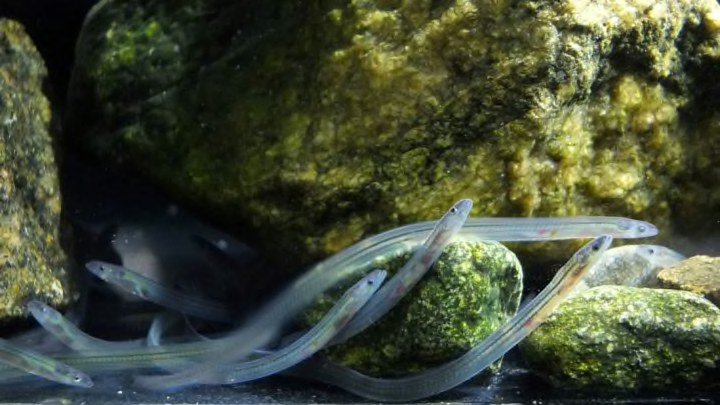

It’s an impressive feat for the little noodles, and scientists wondered how they pull it off. To find out, researchers scooped up a group of newly arrived baby eels on the coast of Norway. They put the eels in a large chamber inside a fjord and let them swim there for a full tidal phase, watching how the eels positioned their bodies and how they swam.

Next, they brought the eels into the lab and repeated the tide-long observation process.

Unsurprisingly, the little tykes knew exactly what they were doing. They consistently turned their bodies to run parallel with magnetic lines, but the direction of those lines varied depending on the phase of the tides. When the tide went out to sea, the majority of eels swam southward, whether in the fjord or in the lab.

These findings are as fascinating as they are vital, as, for all its ingenuity, the European eel is critically endangered. Understanding this animal’s extraordinary life cycle could help conservationists find ways to protect it better in the future.