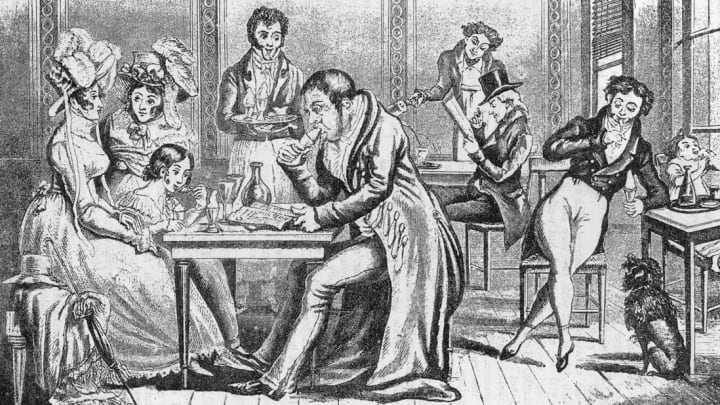

Whether you’re enjoying a movie or eating your feelings, it’s hard to resist a good munch—or as the kids say these days, a nom nom nom. So why not learn about some old words for munching while polishing off those potato chips? Some older words for nibbling and gnawing are onomatopoeic (like scrunch) and other are scientific-sounding (like commanducate). But they’re all worthy words that deserve another chance to get stuck in the lexical craw.

1. AND 2. CHAMM AND CHANK

Chamm, around since the 1930s, is a predecessor to champ, as in chewing rather than being the champion of the world. Speaking of champing, people and animals have been chanking since the 1500s. A use in Gene Stratton-Porter's 1913 novel Laddie: A True Blue Story described some pigs who “chanked up every peach that fell.”

3. AND 4. DENTICATE AND CHUMP

The rare word denticate has an obvious resemblance to one of the most chew-centric professions, dentistry. A 1799 use in Sporting Magazine locates this word right in the lexicon of chewing: “Masticate, denticate, chump, grind and swallow.” Chump? Yep, even chump has been a word for chewing, as seen in an 1854 use by William Makepeace Thackeray: “Sir Brian reads his letters, and chumps his dry toast.”

5. BEGNAW

The prefix be- just doesn’t make new words the way it used to, but it has a lengthy resume of old-timey terms that can make an lexicon-lover smile. One is begnaw, which Shakespeare used figuratively in Richard III: “The worme of conscience still begnaw thy soule.”

6. AND 7. SCRUNCH AND SCRANCH

Few words sounds as much like their meaning as scrunch. Nobody scrunches when they eat applesauce or soup: This is a noisy word, as indicated by a use in a discussion of West English dialects from 1825: “A person may be said to scrunch an apple or a biscuit, if in eating it he made a noise.” You can also scranch.

8. NATTER

The first meanings of this term refer to wagging the gums in another sense: complaining, nagging, gossiping, and yammering. From there it spread to some other uses of the mouth: gnawing and nibbling. The term appeared in John Dalby’s 1888 book Mayroyd of Mytholm: A Romance of the Fells: “It would continually natter at David's heart.” Since that use was figurative, no need to call the cardiologist.

9. AND 10. COMMANDUCATE AND MANDUCATE

Commanducate, at least as old as the late 1500s, means “to chew thoroughly,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary. On the other hand, manducate can mean chewing in general but sometimes has an-ultra specific meaning: to partake of the Eucharist.

11. MUNGE

A less religious sort of consumption is suggested by munge, which is found in Hugh Kelly’s 1770 comedy A Word to the Wise: “You above, in cake-consuming bow'rs, Who thro' whole Sundays munge away your hours.”

12., 13., AND 14. KNABBLE, KNAPPLE, AND KNAB

Knabbling is nibbling, at least since the 1500s. Like a lot of chew words, this one can be figurative. A use in Gideon Harvey’s 1666 book Morbus Anglicus describes “a bone for every Readers discretion to knabble at.” You can also knapple and knab. Roger L'Estrange’s 1692 book Fables of Aesop contains a line that’s relatable in any century: “I had much rather lie Knabbing of Crusts ... in my Own Little Hole.”

15. CHUMBLE

Around since the early 1800s, chumble is one of many chewing words containing the consonant blend ch. An OED example from 1941 describes the worst nightmare of a clothing store owner: “I can hear the sound of moths chumbling the clothes in that chest.”

16. FLETCHERIZE

All these words have their charms, but none have the back story of fletcherize. A Victorian author named Horace Fletcher was called “The Great Masticator” for advocating a preposterous amount of chewing before swallowing. His chew-happy philosophy was called Fletcherism, and a 1904 use in The Daily Chronicle includes another variation: “The Fletcherites preach the gospel of chewing.” A use from Literary Digest in 1903 explains what must have been a novel term: “It is now proposed to speak of the ‘Fletcherizing’ of food that is thoroughly chewed.” And a use in O. Henry’s 1910 book Strictly Business shows how this term could be used figuratively: “Annette Fletcherized large numbers of romantic novels.” All hail Horace Fletcher: the patron saint of chewing.