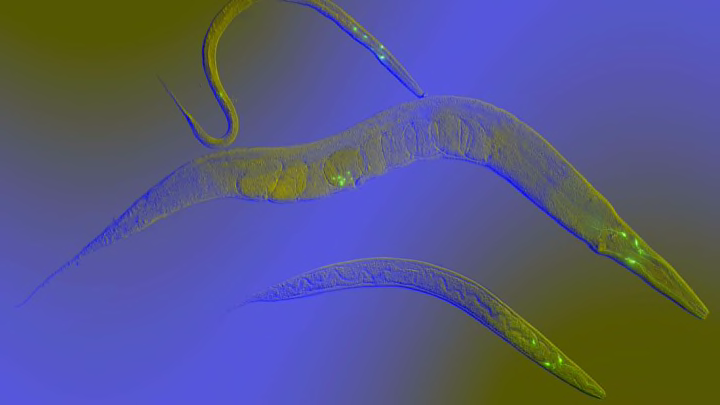

Caenorhabditis elegans may not look much like us, but the primitive worm has a surprising amount in common with humans, biologically speaking—including, as it happens, its response to working out. A new study in BMC Biology analyzed what happens to C. elegans after exercise, finding that their bodies undergo significant physiological changes even after just one session.

Studies have already shown that people benefit from short bursts of exercise, and that in some cases, a very short period of very intense exercise might be more beneficial than a longer but more moderate workout. Research indicates that some of the benefits of working out are immediate—just one workout session has been shown to immediately increase cognitive performance and reduce some of the risk factors of cardiovascular disease.

Because C. elegans shares some biological characteristics with humans, the species plays a huge role in basic biology research, and understanding what happens to C. elegans during exercise can go a long way toward helping us figure out what happens in our own bodies.

In this study, molecular biologists at Rutgers University exercised the nematodes for five, 30, 60, or 90 minutes by either forcing them to crawl across agar or swim. Using microcalorimeters, they found that swimming was a more rigorous activity for the

worms,

and that after 90 minutes of activity, they showed physical responses similar to what a mammal would have: increased metabolic rate, fatigue, changes in the metabolization of fat and carbohydrates, and mitochondrial oxidation in muscles.

While it’s fun to imagine scientists hunched over their lab tables acting as worm swim coaches, the study also establishes a method by which future scientists can study the physiology of exercise. Now that we know that 90-minute swim sessions produce similar physiological responses in C. elegans to workouts for mammals, researchers can use this procedure in designing their own studies. Being able to study the effects of exercise in an animal that doesn’t live that long, like C. elegans, means that “life-long effects of exercise can be measured at a cellular, tissue, and organismal level in unprecedented ways,” they write.