On January 26, 1983, a spreadsheet program called Lotus 1-2-3 burst onto the personal computing scene. Facing a horde of competitors including VisiCalc (the original Apple II "killer app"), Multiplan (from Microsoft), Supercalc (running on CP/M) and Context MBA, 1-2-3 was an upstart, but it had an edge: it was fast.

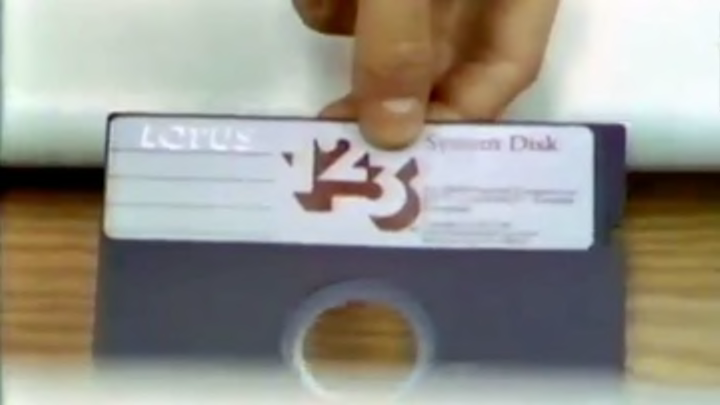

Before we dig in deeper, here's a clip from Triumph of the Nerds showing Lotus 1-2-3 as the IBM PC's first killer app:

In the early years of personal computing, each computer system had a "killer app" that made the entire machine worth buying just for that piece of software. In 1979, the Apple II series found its killer app for small business in VisiCalc, a spreadsheet that automated basic calculations like managing a budget, balancing a checkbook, or keeping track of a (relatively small) supply chain. In the late 70s this was a huge deal -- prior to computerized spreadsheet programs, "spreadsheets" were literally big pieces of paper, and you had to do the math yourself every time any value changed. Simply having a computer re-run the same series of computations saved office workers tons of time, and eliminated some of the worst drudgery associated with finance. Computer spreadsheets also allowed easy forecasting -- "What if we sold 10% more this year, or got this part for 5% off?" -- with instant results. It's hard to imagine now what a revolution this was, but if your job was running the budget every few days, it was sheer magic to change some number and hit Return, then see the updated numbers ripple through automagically.

When IBM introduced its PC in 1981, users wanted to see its killer app -- where was its VisiCalc? (VisiCalc was actually ported to DOS, though it had some limitations.) The "where's my killer app" answer soon came when Lotus 1-2-3 arrived in early 1983. Mitch Kapor, a friend of the developers of VisiCalc, founded Lotus Development Corporation and set out to own the IBM PC market for spreadsheets. Kapor succeeded, and Lotus went public in October of 1983.

What Made 1-2-3 Special

In a word, speed. 1-2-3 was written in assembly language, "close to the metal" as computer nerds like to say. Writing in that computerese assembly language was more difficult for programmers than using a high-level language like C, but the resulting programs ran much faster on the plodding computers of the day. In other words, let the programmers suffer the pain of coding in a language that was Greek to them -- the users would reap the rewards when their program ran quickly.

In addition to its assembly roots, 1-2-3 used special graphics routines that wrote directly to the IBM PC's video memory, rather than passing each character through the operating system to paint onto the screen. This design decision had two outcomes: first, it made the screen update faster (making the program respond faster to user actions like scrolling); second, it meant that the app was locked into the IBM PC hardware. Locking your app into the IBM PC hardware ecosystem was a moderately gutsy business move at the time; if 1-2-3 didn't take off on the IBM PC, it would be harder to move it to another platform because of all its IBM-specific coding (assembling and custom graphics). Apps like VisiCalc existed on multiple platforms, though they generally failed to perform as well, in part because it had to serve multiple kinds of systems.

That IBM PC-exclusive decision was also surprisingly crucial when PC clones began to appear. When you bought a PC clone in the 1980s that promised "100% compatibility" with a true blue IBM machine, that was a nod to apps like 1-2-3 that relied on the specific quirks of the IBM PC's video system. Without perfect compatibility, a clone couldn't run 1-2-3, and indeed testing your clone against 1-2-3 was one way to know whether it was ready for primetime. This led to a homogeneous IBM clone landscape, while the rest of the personal computer industry was spawning various competing systems with their own ecosystems of software -- some good, some great, some crappy -- but none of which could run Lotus 1-2-3 in its original form.

Beyond its speed, 1-2-3 offered charting and graphing, macros, basic database functions, and could even be used as a simplistic word processor. Because it had a broad feature set and was crazy-fast, an office worker in 1983 could spend the day in 1-2-3 and get a lot done.

Lotus 1-2-3 Rocks

This period video gives you a sense of what a big deal 1-2-3 was. It eliminated the so-called "floppy shuffle" of using multiple apps to get your work done. When you used a system lacking multitasking (like the IBM PC's DOS or the Apple II), putting together an integrated report (spreadsheet, graphs, words) was frustrating if you had to use lots of apps. By comparison, 1-2-3 was a frickin' Broadway show. Check this out:

Dan Bricklin on 1-2-3

Lotus 1-2-3 and Dan Bricklin's VisiCalc are the two most historically interesting spreadsheet apps of their era. Part of this interest came from the fact that Bricklin and Kapor (founder of Lotus) were friends and competitors. Yesterday, Bricklin wrote about the history of 1-2-3 on his blog. Here's a snippet:

Getting personal computers onto the desks of office workers everywhere was a very important step in the history of computing. Lotus was a major factor in taking this step. Their later product, Notes, I believe helped get "wired" computers onto those desks and hastened the adoption of web browsers for many reasons (it's a lot easier to get people to try new software and services when they already have the expensive hardware and it's wired and ready to go). While the old Lotus is not around in its old form, its employees have gone on to help create other great things in the computer industry. Mitch has continued his role as an industry statesman, and I hope is enjoying this anniversary. People frequently ask me how I feel about 1-2-3 overtaking my product VisiCalc. While it always feels bad to lose your position as a leader, and not get to participate as much in the benefits that come with that position, I'm really happy that at least it was 1-2-3 that took the mantle from VisiCalc. Mitch and Jonathan Sachs were our friends and they made their product a follow-on (it could read VisiCalc files, so you could move your spreadsheets from VisiCalc to 1-2-3 to Excel to Google Docs without retyping) keeping a lot of the "DNA" of our ideas. Lotus improved on the design of the electronic spreadsheet, so it stayed a major productivity tool. Mitch kept his company here in Massachusetts (Mitch had moved back from Silicon Valley to found it). And our product is still the first in the line and is not forgotten. As a child of the 1950's and 1960's, to know that you made something that changed the world, and that it lives on in products that acknowledge your starting point, is something most people could only dream about and for which I will be forever grateful. The launch of Lotus 1-2-3 helped make that happen and brought personal computing to a large part of business in the process. Happy 30th!

If you want a sense of what 1-2-3 was actually like to use, check out this 80s-tastic training video. (I didn't watch the whole half hour, and I doubt you should.)

One More Video

This video explains the early history of Lotus as a company. Clothing and hairstyles aside, this sounds a lot like the working styles and raw excitement of more recent tech companies like Facebook and Google. The video is shot from the audience of a talk by Mitch Kapor, so the audio isn't great -- but it's still a fascinating historical artifact.

So as you fire up Google Docs or Excel today, think back to 1979 and 1983, the two major inflection points when the killer apps of the past made fortunes for Apple and IBM. Happy 30th, 1-2-3.