A Crudely Drawn Penis Almost Derailed Huck Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is about as American as it gets. Funny, then, that the book was released in England well before it hit shelves in the U.S. Funny, except to author Mark Twain, whose greatest work was almost derailed by a strange prank.

Twain was unhappy with the way he and his previous books had been handled by publishers. Royalties went unpaid. Release dates were pushed back. The books weren’t sufficiently promoted. He decided that for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, he’d start his own publishing house and put the book out himself.

In 1884, he founded Charles L. Webster and Company, named for his business agent, who was made the company’s director. Twain borrowed an idea from an old publisher for his venture: subscription-based sales. Instead of selling copies of the book to stores and letting them sell them to the public, a small army of salesmen employed by Webster and Company would sell the book door-to-door. Armed with a sales prospectus and an advance copy of the book containing sample pages, the sales agents would show off the book to consumers and then get them to “subscribe,” or sign an agreement to pay for a copy of the book when it was later delivered to their home.

The next set of illustrations Twain saw, for chapters 13-30, were more well-received. “This batch of pictures is most rattling good,” he admitted. “They please me exceedingly.”

Again, though, there was a hitch. Twain asked that one of the drawings, which depicted “the King” kissing a girl at the camp meeting in Chapter 20, be removed.

“It is powerful good, but it musn’t go in,” he explained to Webster. “Let’s not make any pictures of the camp meeting. The subject wouldn’t bear illustrating. It is a disgusting thing and the pictures are sure to tell the truth about it too plainly.”

Finally, Twain was happy with all the drawings and the book went to press. The first run was being printed, and advance copies were already out being shown to potential customers, when Webster got a panicked letter from a salesman in Chicago. When the salesman cracked open his sample of the book, he found that someone - maybe a mischievous printer, or one frustrated with delays; maybe Kemble taking revenge for the rejected drawings - had made a last-minute addition to one of the illustration printing plates.

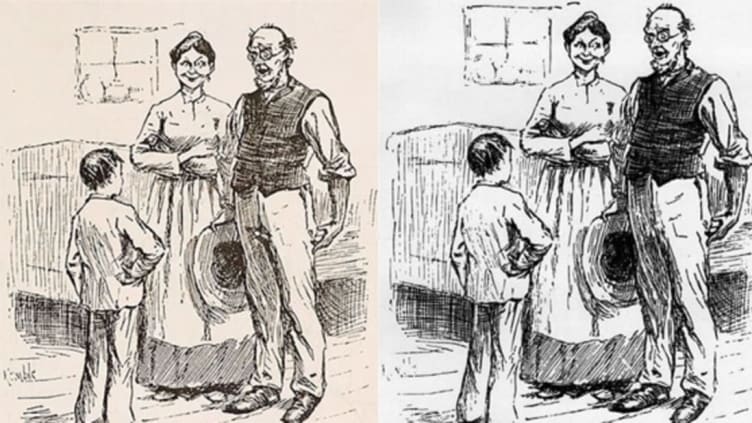

In a picture of Uncle Silas speaking to a young boy while Aunt Sally looks on with a smile, Silas sports a crudely drawn penis, or at least a shadowy bulge in his pants.

Draw Again

There are various versions of the events that followed. One says that only 3,000 advance copies were already made, and only 250 had been sent out. Another says that some 30,000 copies had been printed and were awaiting shipment when Uncle Silas’ exposure was discovered.

Either way, Twain and Webster had a fit, and printed copies with the Silas illustration were ruthlessly hunted down and either destroyed or sent back to the company to be fixed. Meanwhile, Webster had to stop the printing operation, take out the offending plate, have a new one made and put in, and then restart printing to fix the existing books and finish the run, causing weeks of delay in publication. The recall and overhaul meant that the American edition of the book wasn’t released until well after Christmas, in February 1885.

Missing out on Christmas shopping didn’t dent the book’s sales too badly, though. Twain had spent the summer and fall running a publicity campaign that included a lecture tour where he read excerpts from the novel, and news reports about the obscene illustration helped publicize the book in the U.S. and fuel interest in it.

Only a few copies of the complete first edition with the picture of an exposed Uncle Silas are reported to exist, and can command tens of thousands of dollars on the rare book market. That Twain was set back by a prank that would later go on to become a valued collector’s item seems in the spirit of his work, something you’d like to think he came to appreciate, or wish he'd thought of himself.

Book image credit: Hulton Archive