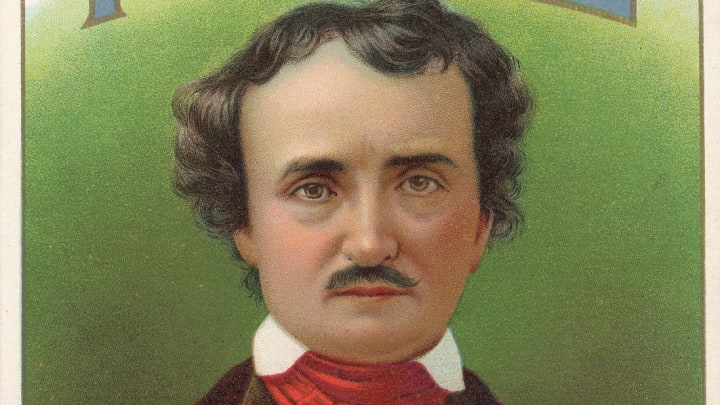

On January 28, 1831, a court-martial tried a young cadet at the U.S. Military Academy on charges of gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders. Sergeant Major Edgar Allan Poe was found guilty of both charges and discharged from the service of the United States only six months after he had arrived at the academy. This is the story of how the author’s military career went so wrong, so fast.

In the Army Now

Edgar Allan Poe’s return to Richmond after his first semester at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville in December 1826 was not the joyous reunion with family and friends that most college freshmen experience. Poe’s friends avoided him. He discovered that his sweetheart, Elmira Royster, had gotten engaged in his absence. A two-year feud between Poe and his foster father, John Allan, erupted in an argument that sent Poe packing.

Eighteen-year-old Poe moved to Boston three months later and quickly arranged the publication of his first book, a collection of poems under the title Tamerlane. Calvin F. S. Thomas published the book, but Poe piled the publication costs on top of the significant gambling debts he’d accrued in school. Despite his investment in the book, Poe didn’t put his name anywhere in it and instead simply gave author’s credit to “A Bostonian,” perhaps hoping that the book would get more attention since Boston was then a literary mecca.

Things didn’t go as planned.

Poe’s money and effort went down the drain when the book received poor distribution and was not reviewed by the local papers. With only a year of higher education, and skill in a single trade that cost him the last of his savings, Poe was broke and essentially unemployable. Like other young men faced with similar situations both before and after him, Poe turned to the government for help.

He enlisted in the Army on May 26, 1827, under the alias of Edgar A. Perry, claiming to be a twenty-two-year-old clerk from Boston. He first served at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor and was later moved to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina, and then Fort Monroe, Virginia, usually earning around $5 a month.

Poe excelled under military discipline and set himself apart from his peers in the eyes of their superiors. Officers at Fort Monroe described Poe as “good, and entirely free from drinking” and “highly worthy of confidence,” and he was soon promoted to “artificer”—a tradesman position that involved preparing artillery shells—and later, sergeant major for artillery.

Poe's fast success didn’t mean he was happy with army life. On the contrary, after two years of a five-year commitment, he badly wanted out, having served “as long as suits my ends or my inclination.” An early discharge would have been difficult to secure, so he approached his commanding officer, Lieutenant Howard, for advice. He disclosed his real name and age to the lieutenant and gave him the rundown of his troubled life. Howard took pity on Poe and agreed to arrange a discharge on one condition: Poe had to reconcile with his foster father, John Allan.

Howard took a crack at Allan first, writing to him to suggest a family reunion and reconciliation with Poe, who would then be able to come home. Allan responded to say that Poe “had better remain as he is until the termination of his enlistment.” Undaunted, Poe next wrote to Allan himself, describing at length how he had changed and was inspired to make something of himself at the United States Military Academy. Allan did not reply to that letter, or several others that Poe subsequently sent.

Even if the letters went unanswered and unread, the universe forced a reconciliation between the two men. In February, 1829, Fanny Allan, John’s wife and Poe’s foster mother, fell ill and died. Both Poe and Allan were grief stricken and the latter was softened enough that he agreed to help Poe end his enlistment and go to West Point the following year.

School of Hard Knocks

While Poe found that the amount of studying required at West Point was, in his words, “incessant,” he flourished at the Academy just as he did during his enlistment. He excelled in mathematics and language, placing seventeenth in his math class and third in French. He even found time to write a few new poems.

But things went downhill when Poe learned that John Allan had fathered illegitimate twins and married a woman 20 years his junior. Poe worried that this meant his foster father would shut him out. These fears were confirmed in late 1830, when Allan wrote to say that he no longer wished to communicate with Poe.

Furious, Poe sent Allan a long letter and revealed all his long-suppressed anger. He told Allan he didn’t have the energy or the finances to stay at the academy and wished to leave. Since the academy required Allan’s permission for Poe to withdraw, he promised that if Allan did not release him, he would get himself kicked out.

Allan did not respond, and Poe did as he promised, racking up an impressive disciplinary record. He earned 44 offenses and 106 demerits in one term and topped the offender’s list the following term with 66 offenses in one month. (There is no mention in West Point’s official records, however, of Poe reporting for drills in a belt, a smile and nothing else, as has often been rumored and given as reason for his expulsion).

By the end of January, he was tried and discharged. But before he left, he squeezed a little more use out of the army. He had persuaded 131 cadets to each give him a dollar and a quarter to finance the printing of a new volume of his poems. When he arrived in New York in February 1831, he released the book, simply called Poems, and dedicated it to his fellow cadets.

This story originally appeared in 2011.