It was 150 years ago today—on May 10, 1869—that "The Last Spike" was driven into America's first transcontinental railroad. This Last Spike was made of gold, so anyone could tell it was important, but there was plenty more to get excited about.

What Railroads Can Do For You

Before the transcontinental railroad, travel from the East to the West Coast took many moons and cost at least $1000 (the equivalent of just under $20,000 today). If you journeyed overland, bandits, foul weather, or unexpected hazards might strand you in mountains, and for any number of reasons—up to and including Divine Wrath—your party might drop from thirst, hunger, or pestilence, leaving bones for strange rodents to gnaw and scatter. If you went by water, the trip would be long and you might get bored, which is a drag.

After the nation-spanning railroad was completed in 1869, a ride from New York to San Francisco could be over in a week, for less than $100. You would be free to spend the whole trip eating and sleeping in comfort, writing love letters to your mistress, and reading, instead of living harrowing tales of privation and danger. Trade benefited as much as passengers. (Think of all that freight!) Even fresh food could be transported over the rail lines. At last, the coasts were tied together.

So if the transcontinental railroad was such a great idea, why didn't they build one earlier?

First, the railroad and steam locomotive had to be invented, which didn't happen until a little into the 19th century. Then, by the time such a project was technologically and logistically feasible, the States were beginning their Great Schism, which would lead to the Civil War; and various North-South debates about the fate of the West, the future of slavery, and the routes of the rails paralyzed negotiations.

The Great Railroad Race

The Civil War actually advanced the transcontinental railroad project, since it freed up the Union to build whatever it wanted without a care for what the Southern grumblers thought. In 1862, then, Congress managed to forge the Pacific Railroad Act, which granted money and land for every mile of rail constructed toward the goal of an East-West connection.

The two companies involved were the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, racing from Omaha and Sacramento, respectively, for as many subsidized miles as they could build before the rails met. (It was a "race" because the total mileage between two points is finite, so an extra mile earned by Union meant one less for Central, and vice versa.) The Union Pacific crews were composed of Irish and German immigrants, Civil War vets, free black citizens, and some Native Americans. The Central Pacific utilized more than 10,000 Chinese employees willing to work for less and in perilous conditions—which was important for Central, since they had to climb and blast their way through the Sierras almost as soon as they left Sacramento.

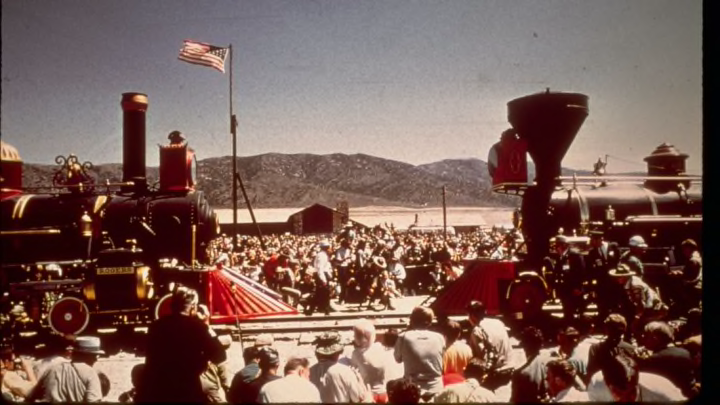

The Tracks Meet at Promontory, Utah

Congress made the fool's mistake of assuming some motivating rationality on the part of the railroad companies, and not just base greed, so they didn't dictate just how, when, or where the rails must meet. When Central and Union crews ran into each other in northern Utah, instead of merging the lines right away, they set off building miles of parallel grading, with each company hoping to acquire more mileage and thus more of the reward money. With a kind of paternal exasperation, then, Congress had to set a junction point; and they chose Promontory, Utah—a little tent town of railroad workers and prostitutes just north of the Great Salt Lake.

Precious Metals and Railroad Fat Cats Make Good News

Since the meeting of the rails was such a meaningful (and publicized) national event, everyone considered it fit to celebrate with extravagant ceremony. Of course, extravagance ought to involve precious metals whenever it can, so four precious spikes were donated to adorn the last tie. There was an iron, silver, and gold spike from Arizona; a silver spike from Nevada; one gold spike from the San Francisco News Letter; and the crowning spike of gold from David Hewes, a friend of Central Pacific magnate Leland Stanford (founder of Stanford University).

Hewes's spike was the first to be made, and it inspired the rest. Hearing of the grand event, Hewes was initially disappointed at a lack of symbolic (and precious metal) objects donated for the ceremony, so he got the ball rolling himself. Hewes ended up having $400 worth of his own gold, from his own hoard, cast into a spike, each side of which was engraved: two with names, one with dates, one with the motto "May God continue the unity of our country as the railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world," and the head with a simple statement: "The Last Spike."

It was not, in fact, the last spike. The precious ceremonial spikes were carefully tapped into a ceremonial tie with a ceremonial silver hammer.

When the dignitaries (Stanford of Central Pacific and Thomas Durant of Union Pacific) tried real hammer swings to seal the deal, they both missed.

One spike was rigged with telegraph wires, so the whole nation could hear the blows of the hammer—something like a "live" broadcast, but with telegraph instead of television, and no commercials—and the publicists made sure to give this one a few good dings. Adding to those taps, a single-word telegram was sent out around the States: "Done." And the nation rejoiced, from coast to coast. But after all the pomp was accomplished, the special spikes and tie were torn up and some unknown railroad workers drove regular iron spikes into a regular tie to complete the transcontinental railroad.

The Verdict

"Never before in our history as a nation has occurred an event in the celebration of which all could participate so heartily, and with so little of mental reservation," the San Francisco News Letter reported. Most spokesmen shared the sentiment. Trouble was, the Chinese laborers had just rioted, other workers had held Durant hostage in his palatial train car while demanding unpaid wages, and of course that last telegraph spelled little but "Doom" to the Native Americans, who were further compressed by the States's new belt and surely had one or two reservations about that.

All in all, it was a strange and potent spectacle, with the golden spike at its center—a scene that might symbolize much more about the many-sided America than those simple and straightforward ideals of Industry and Progress.

This post was originally published in 2009.