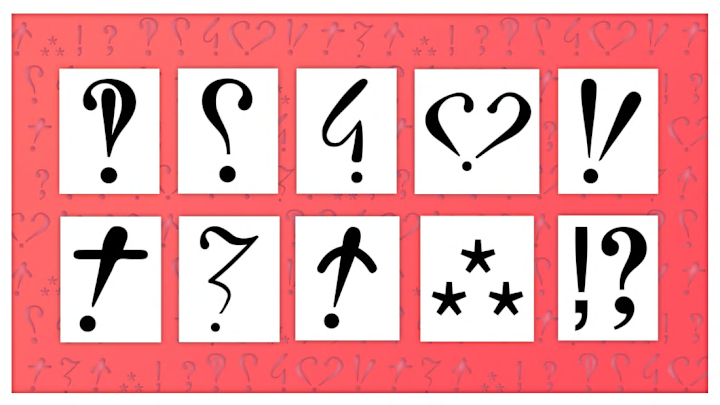

Because sometimes periods, commas, colons, semi-colons, dashes, hyphens, apostrophes, question marks, exclamation points, quotation marks, brackets, parentheses, braces, and ellipses won’t do, here are a few other punctuation marks to work into your everyday communications.

- Interrobang

- Percontation Point or Rhetorical Question Mark

- Irony Mark

- Love Point

- Acclamation Point

- Certitude Point

- Doubt Point

- Authority Point

- SarcMark

- Snark Mark

- Asterism

- Exclamation Comma and Question Comma

Interrobang

You probably already know the interrobang, thanks to its excellent moniker and popularity. Though the combination exclamation point and question mark can be replaced by using one of each, they can also be combined into a single glyph. The interrobang was invented by advertising executive Martin Speckter in 1962; according to his obituary in The New York Times, the interrobang was “said to be the typographical equivalent of a grimace or a shrug of the shoulders. It applied solely to the rhetorical, Mr. Speckter said, when a writer wished to convey incredulity.” The name is derived from the Latin word interrogatio, which means “questioning,” and bang—how printers refer to the exclamation mark.

Percontation Point or Rhetorical Question Mark

The backward question mark was proposed by printer Henry Denham in the 16th century as an end to a rhetorical question. According to Lynne Truss in the book Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, “it didn’t catch on.”

Irony Mark

According to Keith Houston, author of Shady Characters, it was British philosopher John Wilkins who first suggested an irony mark, which he thought should be an inverted exclamation point.

Next came Alcanter de Brahm, who introduced his own irony mark (above)—which de Brahm said took “the form of a whip”— in the 19th century. Then, in 1966, French author Hervé Bazin proposed his irony mark, which looks a bit like an exclamation point with a lowercase u through the middle [PDF], in his book, Plumons l’Oiseau, along with five other pieces of punctuation.

Love Point

Among Bazin’s proposed new punctuation marks was the love point. It was composed of two mirrored question marks that formed a heart and shared a point. The intended use, of course, was to denote a statement of affection or love, as in “Happy anniversary [love point]” or “I have warm fuzzies [love point].”

Acclamation Point

Bazin described this mark as “the stylistic representation of those two little flags that float above the tour bus when a president comes to town.” Acclamation means “a loud shout or other demonstration of welcome, goodwill, or approval,” so you could use it to say “I’m so happy to see you [acclamation point]” or “Viva Las Vegas [acclamation point].”

Certitude Point

Need to say something with unwavering conviction? End your declaration with the certitude point, another of Bazin’s designs, which is an exclamation point with a line through it. As Phil Jamieson writes at Proofread Now’s GrammarPhile blog, “This punctuation would best be used instead of writing in all caps.”

Doubt Point

Another Bazin creation, the doubt point—which looks a little like a cross between the letter z and a question mark—is the opposite of the certitude point, and thus is used to end a sentence with a note of skepticism.

Authority Point

Bazin’s authority point “shades your sentence” with a note of expertise, “like a parasol over a sultan.” (“Well, I was there and that's what happened [authority point].”) Likewise, it’s also used to indicate an order or advice that should be taken seriously, as it comes from a voice of authority.

Unfortunately, as Houston writes at the BBC, “Bazin’s creations were doomed to fail from the start. Though his new symbols looked familiar, crucially, they were impossible to type on a typewriter. The author himself never used them after Plumons l’Oiseau and the book’s playful tone discouraged other writers from taking them up too, so that today the love point, irony point, and the rest are little more than curiosities.”

SarcMark

The SarcMark (short for sarcasm mark) looks like a swirl with a dot in the middle. According to its website, “Its creator, Douglas Sak, was writing an email to a friend and was attempting to be sarcastic. It occurred to him that the English language, and perhaps other languages, lacked a punctuation mark to denote sarcasm.” The SarcMark was born—and trademarked—and it debuted in 2010. While the SarcMark hasn’t seen widespread use, Saks markets it as “the official, easy-to-use punctuation mark to emphasize a sarcastic phrase, sentence or message.” Because half the fun of sarcasm is pointing it out [SarcMark].

Snark Mark

This, like the SarcMark, is used to indicate that a sentence should be understood beyond the literal meaning. Unlike the SarcMark, however, this one is copyright-free and easy to type: It's just a period followed by a tilde. It was created by typographer Choz Cunningham in 2007.

Asterism

According to Houston, this triangular trio of asterisks was “named for a constellation of stars and used as late as the 1850s to indicate ‘a note of considerable length, which has no reference.’”

Exclamation Comma and Question Comma

According to the Huffington Post, Leonard Storch, Ernst van Haagen, and Sigmund Silber created both the exclamation comma and the question comma—an exclamation mark with a comma for a bottom point, and a question mark with a comma for a point, respectively—in 1992. The patent for the marks (which expired in 1995) reads:

“Using two new punctuation marks, the question comma and the exclamation comma … inquisitiveness and exclamation may be expressed within a written sentence structure, so that thoughts may be more easily and clearly conveyed to readers. The new punctuation marks are for use within a written sentence between words as a comma, but with more feeling or inquisitiveness. This affords an author greater choice of method of punctuating, e.g., to reflect spoken language more closely. Moreover, the new punctuation fits rather neatly into the scheme of things, simply filling a gap, with a little or no explanation needed.”

The patent closes with an imagining of what a reader might “silently remark” when seeing the marks for the first time: “Clever [exclamation comma] funny I never saw one of those before.”

Read More About Punctuation:

A version of this article ran in 2013; it has been updated for 2024.